فهرست مطالب

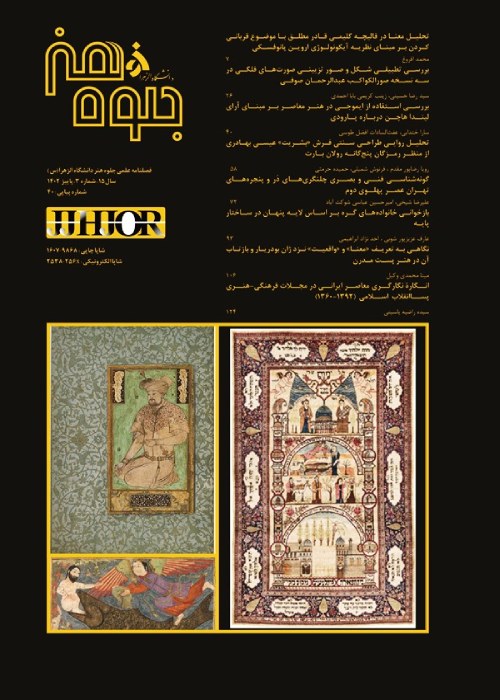

مجله جلوه هنر

سال پانزدهم شماره 3 (پاییز 1402)

- تاریخ انتشار: 1402/07/01

- تعداد عناوین: 8

-

-

صفحات 7-25قالیچه های تصویری کلیمی با وجه دینی و نمادین، یکی از ساحت های قابل مطالعه در بستر مطالعات نظری از جمله نظریه و رویکرد آیکونولوژی (شمایل شناسی) است؛ که به جهت تحلیل و تفسیر متون تصویری و دست یابی به معنای عمیق یک تصویر از طریق مضمون های روایی، کلامی و نمادین مرتبط با آن با در نظر گرفتن بسیاری از ویژگی های ساختاری و محتوایی اثر، می تواند قابل مطالعه و بررسی باشد. قالیچه تصویری با عنوان قادر مطلق و موضوع محوری قربانی کردن ابراهیم نبی، از مهم ترین قالیچه های رایج در سنت قالی بافی کلیمیان است؛ که در این پژوهش، به شیوه آیکونولوژی مورد مطالعه قرارخواهد گرفت. پرسش مطروحه در باب موضوع این است که: مضامین کلامی، روایی و تصویری نهفته در روایت قربانی کردن اسماعیل (اسحاق) کدام است و این عناصر در پی بیان چه مفاهیم یا پیامی هستند؟ پی جویی در آشکار کردن، فهم و درک معناها و لایه های زیرین داستان از طریق شناخت ابعاد صوری (عناصر و نقش مایه ها) و محتوایی و روابط بین آن ها، هدف این پژوهش است. یافته های این پژوهش در یک سطح، شامل یادآوری آموزه های بنیادین و اخلاقی دین موسوی و هویت کلیمی است که در قالب نظام های کلامی و تصویری نمادین، نقش پردازی شده است؛ و در سطحی دیگر، که پیام و هدف اصلی را در بر می گیرد، ابلاغ، تاکید و نشان دادن آموزه دینی، اخلاقی و حکمی «اطاعت و تسلیم بودن» در برابر معبود از طریق آیین «قربانی» کردن و گذشتن از ممتازترین داشته ها و خواست ها می باشد. این پژوهش از نوع کیفی و بنیادین، روش تحقیق توصیفی-تحلیلی و شیوه گردآوری داده ها، کتابخانه ای است.کلیدواژگان: واژه های کلیدی: دین، کلیمی (یهودی)، هنر، قالیچه، قربانی کردن

-

صفحات 26-39

اخترشناسی از قدیمی ترین دانش های بشری است. «ابوالحسن عبدالرحمن صوفی رازی فسوی» ستاره شناس برجسته ایرانی سده چهارم است که در دوران دیلمیان در فارس می زیست. وی کتاب صورالکواکب را که نسخه تصحیح شده ای از المجسطی بطلمیوس بود، بر اساس مشاهدات رصدی خودش تالیف کرد. هدف از این پژوهش، شناسایی انواع صورت های فلکی مصور، تجزیه و تحلیل ساختار تصویری و صور تزیینی و واکاوی وجوه افتراق و اشتراک آن ها در سه نسخه مصور صورالکواکب عبدالرحمان صوفی مربوط به قرن های 6، 9 و 12 هجری قمری می باشند. پرسش های پژوهش عبارتند از: 1) ویژگی های بصری در سه نسخه مصور صوالکواکب در جهت نمایش اشکال و بروج دوازده گانه کدامند؟ 2) شکل و صور تزیینی صورت های فلکی مصور دارای چه وجوه افتراق و اشتراکی هستند؟ این پژوهش براساس هدف، بنیادی و از نظر ماهیت توصیفی-تحلیلی با مطالعه تطبیقی است. داده ها با جستجو در منابع کتابخانه ای و از طریق مشاهده نسخ، به دست آمده اند. ابزار نمونه گیری ، شناسه، فیش، مشاهده و ابزار پویش گری نوین است. شیوه نمونه گیری مبتنی بر هدف غیراحتمالی است. جامعه پژوهش متشکل از تصاویر بروج دوازده گانه از نسخه های صورالکواکب عبدالرحمان صوفی موجود در موزه برلین، شامل 54 تصویر، نسخه موجود در موزه متروپولیتن شامل 257 تصویر و نسخه موجود در موزه متروپولیتن شامل 78 تصویراست. هم چنین، روش تحلیل نمونه های منتخب کیفی است. نتایج پژوهش گویای آن است که، از ویژگی های بصری مشترک در هر سه نسخه، استفاده از عنصر خط در بازنمایی تصاویر است؛ به گونه ای که در هر سه نسخه به کیفیت و تندی و کندی خط و نیز بهره گیری از آن در نمایش عمق نمایی بهره گرفته شده است. اگر چه در بعضی صفحات کادر حالت معمول را دارد؛ اما هنرمندان در این ترکیب به فرا رفتن تصویر از کادر توجه نموده اند. هم چنین، نوع فضاسازی با ترکیب متن و تصویر همراه است که در صفحات مربوط به برج ها با غلبه تصویر در نیمه بالا یا پایین صفحه ترکیب بندی شکل گرفته است.

کلیدواژگان: صورت های فلکی، صورالکواکب، عبدالرحمان صوفی، نجوم، نگارگری ایرانی -

صفحات 40-57

ایموجی ها تصویر- واژه های استاندارد شده ای هستند که به منظور تاکید بر لحن پیام، کارکردهای احساسی، گفتگوگشایی و انتقال وضعیت ذهنی پیام د هنده مورد استفاده قرار می گیرند. علاوه بر نقش گسترده ارتباطی ایموجی ها در شبکه های اجتماعی مجازی امروزه شاهد ورود تصاویر ایموجی به سایر زمینه های فرهنگی، تجاری و حتی هنرهای تجسمی هستیم. انتقال این تصاویر از متن فرهنگی به متن هنری و تقلید از آن ها چگونه می تواند پارودی ایجاد نماید؟ هدف نوشتار حاضر این است که، با در نظر گرفتن «نظریه پارودی لیندا هاچن»، استفاده از ایموجی ها در هنر معاصر و چگونگی ایجاد پارودی توسط آن ها را تحلیل و بررسی نماید. این پژوهش به لحاظ هدف، پژوهشی بنیادین و بر اساس روش پژوهشی توصیفی - تحلیلی است. نوع داده و تجزیه و تحلیل آن کیفی است و در گردآوری داده ها از منابع کتابخانه ای استفاده شده است. این نوشتار به کمک نظریه پارودی لیندا هاچن به بررسی هشت نمونه از آثاری (هنر تجسمی) پرداخته است که از تصاویر ایموجی استفاده کرده اند. بر مبنای آرای هاچن، وجود موقعیت آیرونیک در تقلید شرطی مهم در ایجاد پارودی است. او هم چنین، برای رابطه پارودی با متن اولیه و رمزگذاری و رمزگشایی آن اهمیت قایل است. نتایج بررسی نشان می دهند، انتقال تصاویر ایموجی از متن فرهنگی به متن هنری موقعیت آیرونیک ایجاد کرده است. این آثار رابطه ای شوخ طبعانه، بازی وار یا خنثی با متن اولیه خود دارند. هنرمند در رمزگذاری این آثار از کدهای متفاوت زیبایی شناسانه، فرهنگی، اجتماعی، روان شناسانه و... استفاده کرده است که مخاطب بنا بر پیشینه فرهنگی و اجتماعی خود قادر به رمزگشایی از آن ها خواهد بود.

کلیدواژگان: هنر معاصر، لیندا هاچن، پارودی، آیرونی، ایموجی -

صفحات 58-71

طراحی سنتی، هنر طراحی نقوش اسلیمی و ختایی بر روی قوس های حلزونی و افشان بر اساس تعادل و انرژی بصری است. در این نقوش، دو وجه صورت و معنا جایگاهی توامان دارند که از این منظر، می توان آن ها را هم چون واژگانی در نظر گرفت که با هدف روایت مندی در محورهای هم نشینی و جانشینی معناداری حضور یافته اند. توجه بر بعد معنایی نقوش، ترفیع جایگاه آن ها را از صور تزیینی به صور روایت مند و معناآفرین موجب می گردد که مغفول ماندن این مهم در بستر پژوهشی هنر طراحی سنتی ایران بر ضرورت بررسی آن می افزاید. شناخت و تحلیل این ویژگی به اتخاذ رویکردی منطبق با مباحث تحلیل روایت هم چون رمزگان روایی رولان بارت منوط می شود که بر مبنای روابط شبکه ای رمزگان های هرمنوتیک، کنشی، معنایی، نمادین و فرهنگی محوریت یافته است. از همین رو، مقاله حاضر با روش توصیفی- تحلیلی به مطالعه موردی هنر طراحی سنتی در فرش «بشریت» می پردازد و عناصر بصری آن را از منظر روایت مندی، با طرح این پرسش که: رهیافت های معنازایانه نقوش در روایت فرش«بشریت» بر اساس رمزگان روایی بارت کدامند؟ مورد مطالعه قرار می دهد. توجه بر روابط معناآفرین عناصر بصری حاکی از آن است که نقوش اسلیمی و ختایی با خاستگاه معنایی ایران باستان و باورهای اسلامی به بازنمایی داستان آفرینش از هبوط تا زایش و تداوم نسل بشریت پرداخته اند. در این راستا، پیکر های مرد، زن و کودک در پیوند با یک دیگر از سویی و در ارتباط با نقوش حیوانی از سویی دیگر بر مواردی هم چون کنش محافظت، کمال یافتگی و نمادپردازی های جنسیتی که در مولفه های اصلی بشریت و تداوم نسل به اشتراک رسیده اند، اشاره دارند.

کلیدواژگان: طراحی سنتی، عیسی بهادری، فرش بشریت، روایت مندی، رمزگان روایی بارت -

صفحات 72-92

ابنیه تهران در دوره پهلوی دوم دارای چلنگری با طرح های متنوع هستند که نشان از هنر دست آهنگران تهرانی است. هدف مقاله، بررسی شیوه طراحی، ساخت و تکنیک های به کار رفته در چلنگری های در و پنجره تهران دوره پهلوی دوم است و به دنبال پاسخ بدین پرسش هاست: 1) شیوه طراحی، ساخت و تکنیک چلنگری (پنجره و در) ها در تهران چیست؟ و 2) نقوش آن ها کدامند؟ روش پژوهش به صورت توصیفی - تحلیلی و گردآوری اطلاعات، کتابخانه ای و به ویژه میدانی که تعداد نمونه ها 900 عدد پنجره و در، جمع آوری، آنالیز و تحلیل شده است. یافته ها نشان می دهند که، شیوه طراحی به صورت ساده و انتزاعی و نیمه انتزاعی بوده و نحوه گسترش نقوش مستقل (تکی)، قرینه (یک - دوم، یک - چهارم)، واگیره ای (4*1، 4*3، 2*3، 4*4، 2*6، 4*6، 3*1، 3*2، 4*2، 5*4) هستند. نحوه ساخت و تکنیک نیز طرح موردنظر را روی صفحه تخمین کپی کرده و سپس، به وسیله تسمه های فلزی به پهنای 2 سانتی متر و قطر 5/0 سانتی متر و گاهی، ورقه های آهن نقوش را آماده و روی در و قاب پنجره نصب می کنند. نقوش در پنج دسته انسانی، حیوانی، گیاهی، هندسی و گره چینی، انتزاعی هستند. تنوع طراحی، شیوه گسترش و نقوش در چلنگری های این دوره، پیرو نقش مایه های گره ایرانی بر آجر، چوب و به ویژه، کاشی کاری، نقاشی های انتزاعی مانند پیت موندریان و مکاتب قرن 19م. (سوپره ماتیسم، ریونیسم، کنستراکتیویسم) بوده و هم چنین، استفاده از نقوش ایرانی در این دوره کم رنگ شده و غالب نقوش تابع مدرنیته حاکم در ایران هستند. چلنگری ها در این دوره، ریشه هویتی ایرانی - اروپایی داشته و تمامی نقوش و فرم ها از ابعاد و شکل در و پنجره ها تبعیت می کنند.

کلیدواژگان: معماری، تهران، پهلوی دوم، چلنگری، در - پنجره -

صفحات 93-105

گره ها الگو های هندسی منطبق بر قواعد ریاضیات هستند که در عین پای بندی به قواعد ریاضی دارای ساختاری انعطاف پذیر برای تنوع در طراحی هستند. این انعطاف پذیری از آن جا شکل می گیرد که، گره هایی که از یک ساختار واحد مشتق می شوند می توانند به طرح های مختلف در خانواده های الگوی شان تقسیم شوند. دسته بندی خانواده های گره بر اساس زاویه بین خطوط شمسه تعیین می شود که تند، واسطه، کند و شل را شامل می شود. علی رغم این که مطالعات انجام یافته نشان می دهند در دسته بندی های مذکور، تقسیم بندی خانواده های گره، متکی بر واحد 36 درجه هستند؛ اما این زاویه در همه گره ها صدق نمی کند و گره های متمایزی وجود دارند که واحد های زوایای خانواده گره در آن ها متمایز است. هدف این پژوهش، بررسی خانواده های گره بر اساس شناخت ساختار های هندسی آن ها و یافتن ارتباط بین زوایا در خانواده های مختلف و ساختار گره ها است؛ تا به این پرسش ها پاسخ دهد: 1) علت تنوع زوایای بین خطوط شمسه -که سبب دسته بندی گره ها در انواع خانواده های الگو می شود- چیست؟ و 2) این پیمون بندی زوایا بر اساس چه ساختاری انتظام می یابد؟ این پژوهش با روش توصیفی-تحلیلی و با گردآوری اطلاعات کتابخانه ای کار شده است. نتایج پژوهش نشان می دهند: تنوع پذیری در خانواده های الگو ارتباط مستقیمی بین موزاییک کاری مولد پایه و خانواده های شان دارد؛ و بر اساس پیمون بندی به واسطه نقاط میانی اضلاع چندضلعی اصلی در موزاییک کاری مولد پایه شکل می گیرد، زاویه خانواده های گره تعیین می شود که این پیمون بندی بر اساس نقاط میانی با تقسیم شعاعی دایره رابطه برقرار می کند.

کلیدواژگان: گره چینی، موزاییک کاری مولد، تند، واسط، کند، شل -

صفحات 106-123

پست مدرنیسم، چه در نظریه و چه در هنر، با وضعیتی معناگریز و شناخت ناپذیر مواجه است و تعین ستیزی و عدم قطعیت از بن مایه های اصلی آن به شمار می آید. بودریار به عنوان یکی از اثرگذارترین نظریه پردازان و ناقدان پست مدرنیسم، محور اصلی بحث خود را نقد رسانه های ارتباطی جدید، بی معنا شدن نشانه ها و طرح مباحثی چون بیش واقعیت، از دست رفتن واقعیت و وانموده ها قرار داده است. او ضمن به چالش کشیدن پیکربندی فرهنگی دوره پست مدرن، بر این باور است که در دنیای امروز هر چه رسانه های مجازی پیشرفت کرده و به واسطه آن حجم اطلاعات فزونی یافته، دلالت و معنا تنزل یافته است؛ به طوری که در عصر حاضر دیگر دست یابی به واقعیت ناممکن گردیده است. گرچه نظریات وی توسط برخی اندیشمندان به صورت جدی نقد شده اند، اما هم چنان یکی از موثرترین آرا در اندیشه پسامدرن به شمار می آید. مقاله حاضر، با روش توصیفی تحلیلی صورت گرفته و ضمن شرح نظریات بودریار در باب معنا و واقعیت آثار برخی هنرمندان را از منظر آرای این متفکر مورد خوانش و تحلیل قرار داده است. طبق یافته های پژوهش، مباحثی چون ناپدیدی معنا و از دست رفتن واقعیت در آثار بولین، بیش واقعیت و وانموده در پیکره های هانسون و ادی، تسلط همه جانبه فضای مجازی در آثار پایک، تضارب میان واقعیت و تصویر در اثری از مالر و فضای متکثر در منظره سازی های ادواردز و هم چنین آثار فتوکلاژ هاکنی، ضمن مشابهت مفهومی با تعاریف بودریار از «معنا» و «واقعیت»، همگی موید تعامل میان نظریه و عمل در مصادیق هنر پست مدرن هستند.

کلیدواژگان: ژان بودریار، از دست رفتن معنا، حادواقعیت، پایان واقعیت، هنر پست مدرن -

صفحات 124-142

با پیروزی انقلاب اسلامی به هنرهای اصیل ایرانی از جمله نگارگری توجه و تاکید شد و به عنوان مبنایی برای ارجاع به هویت ایرانی در هنر معاصر ایران در نظر آورده شد. با هدف بازجست تصویر امروز هنر نگارگری معاصر، سوال این است که انگاره نگارگری معاصر ایرانی در مجلات فرهنگی-هنری در سه دهه پس از انقلاب چگونه برساخته شده است؟ بدین منظور با مطالعه اسنادی، موضوع پژوهش، از طریق تحلیل مضامین شکل داده شده در خصوص نگارگری در 12 مجله: فصلنامه هنر، کیهان فرهنگی، سوره، هنر معاصر، هنرهای تجسمی، بیناب، تندیس، گلستان هنر، ادبستان فرهنگ و هنر، کلک، آدینه و دنیای سخن، در سه دهه پس از انقلاب اسلامی واکاوی شده است. نتایج نشان دادند که، در جریان اندیشه ورزی مجلات مذکور، انگاره های متفاوتی از نگارگری معاصر ایران در میانه سه پارادایم «سنت گرایی، نوسنت گرایی و نوگرایی»، برساخته شده که متاثر از نگاه به زبان جهانی هنر و عصر و زمان، در هر پارادایم متفاوت می نماید.

کلیدواژگان: نگارگری، معاصریت، مجلات هنری، سنت گرایی، نوگرایی

-

Pages 7-25Studying the textual and contextual aspects of traditional and applied arts offers a pathway for the expansion and enhancement of the discourse analysis concerning ethnic art.This avenue opens the way and helps the audience understand the inner meanings of the narrative, verbal expressions and visual systems, and structures of the text of the artworks. Indigenious arts, especially Jewish pictorial rugs with religious and symbolic faces present an area ripe for examination within the realm of theoretical investigations, inclusive of the theory and methodology of iconology.This approach delves into the analysis and interpretation of visual compositions, aiming to unearth the profound essence of an image through its narrative, qualitative, and symbolic components, intricately woven together, while considering various structural and thematic facets of the piece. Image rugs are an expression of indigenious arts , offering a fusion of visual and textual discourse centered upon a foundation of objective narratives entwined with spiritual, national, and mythological subjects.Fabricated within specific temporal confines, these artworks serve as a means to preserve beliefs, ideals, epics, and ethnocultural memories. In the context of religiously themed works, these woven creations encapsulate not only images, visual elements, and aesthetics but also enduring ancient symbolic notions, archetypal constructs, and allegorical accounts.Deciphering these multifaceted dimensions mandates a grasp of the historical, cultural, and artistic contexts. This crucial undertaking is facilitated by methodologies such as iconology, denoting the science of image interpretation and analysis. This involves referencing textual sources that underpin the subject matter and concepts depicted within these works, while also scrutinizing the visual components to uncover latent objectives concealed behind the visual narrative. These woven treasures, with the theme of famous stories and events in the Jewish religion, as well as figures of prophecy and sanctity, are a type of carpet weaving art of the Qajar community. In this research, the painted narratives and elements in the context of one of the examples of this type of weaving, namely the "Ghader-e Motlagh" carpet, are analyzed and explained from the perspective of the artistic lens of iconology.Investigating the images and the portrayal of symbolic and allegorical themes and concepts within artistic and visual compositions encapsulates a comprehensive, overarching description of this approach. This methodology strives to fathom images (icons) as entities transcending mere visual representation, striving to convey messages to the audience that surpass the surface.The "Ghader-e Motlagh" rug,, with the central theme of the sacrifice of Prophet Abraham, is one of the most important carpets in the tradition of Jewish carpet weaving. This rug is subject to an iconological analysis in this study. The question raised about the topic is what are verbal, narrative, and visual themes hidden in the narration of the sacrifice of Isaac.The research endeavor aims to unearth and comprehend the meanings and concealed strata of the narrative through an exploration of both formal dimensions (elements and motifs) and the intricate interplay between them.The findings of this research encompass a twofold significance. Firstly, they serve to reiterate the foundational moral tenets of the Judaic faith and Jewish identity. These tenets are presented in the form of theological systems, vividly depicted as symbolic imagery. Secondly, the study unveils the core message and intent of the narrative: prophecy, accentuating the religious, moral, and philosophical doctrine of "obedience and submission" to the divine through the rite of "sacrifice," which entails forsaking cherished possessions and desires. The concept of sacrifice stands as an ancient archetype, woven throughout history, religions, tribes, and cultures, often at the behest of deities and adherents.The research methodology is qualitative and developmental, employing a Descriptive-analytical approach. The data collection method is rooted in library research. Examining the "Ghader-e Motlagh" rug exposes a melange of icons, including motifs of sacrificial sons, humans, animals, and flora (Bidmanjoon and cypress tree), as well as inscriptions, architectural elements, and more. These components, harmoniously integrated, aid in the revelation of the intended hidden meanings. Especially within spiritual systems, these symbols embody a pursuit of perfection. This study resides within the realm of qualitative research, characterized by its descriptive-analytical nature, while its purpose assumes a developmental trajectory. Data collection relies on library resources. . Concurrently, the research constitutes a case study, with data analysis adopting the iconological or iconographic approach. The purpose of this research is to analyze and interpret the written and visual themes related to the topic of sacrifice in the studied carpet. Iconology, which is referred to as the science of image interpretation and explanation, is made up of two words "icon" which means image and "logos" which means knowledge. In fact, iconology is the study of the logos of words, ideas, discourses, or recognition of icons or images, or similarities (Metchell, 1986, 1). ). While its origins trace back to ancient Greece, with Philocentrasnus' Book of Icons and Akmarasnis' literary style adaptation (Mokhtarian, 1390, 110), ), this approach found a distinct footing in the 19th century AD (Nasri, 1397, 18). Over time, it was Warburg who developed iconology in the late 19th century in order to apply it to various subjects. He not only extended iconography to religioussubjects but also was able to apply the defining range of iconographic methods in order to provide knowledge and the cultural history of art in a comprehensive manner. This method was later called iconology (ibid.), and Panofsky, one of Warburg's most prominent students, was able to structure this method. Iconology is "not only the description of icons - like iconography - but also the interpretation of images and symbols by revealing the interpretive aspect" (Namvar Motlagh, 2013, 73). Panofsky's ethnographic approach, aiming to discern the cultural conceptions attached to images, illuminates unexplored facets of a culture and its worldview (Keshavarz Afshar & Samanian, 2016, 96). The icon's essence, poised between sign and subject, invites a deep cultural probe for an understanding of its intrinsic meanings, aligning with elements deeply embedded within culture.Ergo, iconology, as the science of interpreting and explicating icons or images, strives to unearth the inherent meanings encapsulated within artworks and discern their symbolic significance. Concurrently, this endeavor necessitates a familiarity with the symbolic horizon of the icons or images, grounded in their cultural underpinnings spanning mythology, religion, philosophy, and history (Dayeri & Ashuri, 2015, 21).The theoretical framework of iconology unfolds across three stages. Pre-iconography phase constitutes the initial tier of comprehension. This phase entails an examination and description of the artwork (in this study, the selected carpet) and its concrete and tangible significance.This level encompasses a combination of both the real and expressive dimensions of meaning. Describing a work of art at this level necessitates knowingan understanding of its historical conte, its method, and style resemblances to comparable works, as well as relevant phenomena and themes. This level operates on the premise that visual constituents within the image are fashioned under the influence of specific factors. The subsequent phase, iconographic analysis, delves into the exploration of the central and conventional meanings entrenched within the artistic creation. This stage mandates a grasp of specific themes and concepts, entailing familiarity with a wide spectrum of motifs. Referred to as iconographic analysis, this level of meaning embodies the interplay between artistic motifs and their compositional form to construct a secondary, conventional meaning (Panofsky, 2012, 103).The secondary meaning in the field of art is the meaning that a person achieves with the subject or at a higher level with their theme by establishing a mutual relationship between artistic motifs and the form of their composition (Panofsky, 1972, 6).Unlike the prior level, this mental facet encapsulates allegorical manifestations and cultural codes, acknowledged, condensed, and institutionalized within ethnic groups.The third and final stage entails the analysis of iconology or the content-driven meaning of an artwork, culminating in iconological interpretation. This phase demands a profound comprehension of the culture in which the work was conceived, encompassing its worldview, principles, values, religious tenets, cultural elements, social dynamics, and philosophical orientations. To engage in this level of interpretation, the analyst must grasp the historical journey of symbols and signs. This tier of meaning assumes an authorial essence, evolving through intuitive processes (Panofsky, 1972, 7-9). Crucially, the third level of interpretation amalgamates the preceding two stages, crafting a coherent and inseparable progression.Keywords: Jew, Religion, Art, Rug, sacrifice

-

Pages 26-39

Astrology, one of humanity's oldest sciences, has a rich history of exploration Abolhassan Abdurrahman Sufi Razi Fasavi is a prominent Iranian mathematician and astronomer of the 4th century who lived in Fars during the Dilmian period. He authored the book "Sural al-Kawakb," a corrected rendition of Ptolemy's "al-Majsati," which was rooted in his personal astronomical observations. The objective of this research is to identify the types of illustrated constellations, analyze the image structure and decorative images, and analyze their differences and commonalities in three illustrated versions of Abdur Rahman Sufi's constellations, related to the 6th, 9th, and 12th centuries of the lunar calendar. The research questions are as followed: 1 What are the visual characteristics present in the three illustrated constellations versions that depict the shapes and symbols of the twelve zodiac signs? What discrepancies and commonalities exist within the decorative forms of the illustrated constellations? This research adopts a fundamental, descriptive-analytical approach with a comparative study framework. Data collection entails library research, direct observation of copies, and utilization of modern tools such as digital equipment, photography, and scanning. The study's population encompasses three illustrated versions of Abdur Rahman Sufi's constellations, specifically: Version numbered 64615782, consisting of 54 images, held in the Berlin Museum. Version 13.160.10, containing 257 images, housed in the Metropolitan Museum. Version 1975.192.2, comprising 78 images, also housed in the Metropolitan Museum. The non-probability purposive sampling method is employed, complemented by qualitative analysis of selected samples. Findings unveil a shared visual attribute in all three versions: the deliberate use of line elements in image representation. This includes a deliberate manipulation of line quality, speed, and rhythm to convey visual depth. Another shared feature is the emphasis on the role of the frame in visual presentation. Astrology is the study of changes, physical and chemical characteristics of the position and movement of "celestial objects" such as stars, planets, galaxies and celestial events such as the aurora borealis and cosmic radiation originating outside the Earth's atmosphere. In early civilizations, astronomers carefully studied the night sky with simple astronomical instruments. (این پاراگراف به نظر اضافه است. Abolhassan Abdurrahman Sufi Razi Fasavi, the leader of "Islamic Renaissance"era, named by Adam Metz, changed the way we look at the stars in the sky and is recognized as one of the most influential astronomers in the world. He devoted his life to advancing our comprehension of the stars and constellations. He wrote the book Sural al-Kawakb, which was a corrected version of Ptolemy's al-Majsati, based on his observations, and described the position, color and magnitude of 1081 celestial objects In astronomy, constellations denote a grouping of stars that are proximate, forming distinct shapes akin to objects or creatures in the human mind. Abd al-Rahman Sufi is the pineering individual who depicted the constellations and the twelve constellations in a written and precise manner, and his drawings in the book Sur al-Kawakb became a global visual reference in the creation of the celestial spheres. In this book, he discusses the forty-eight constellations known as the fixed stars, which, according to the medieval conception of the universe, resided in the eighth of the nine spheres around the Earth. The constellations each appear twice in the mirror image seen from Earth and from the sky. The work of Abd al-Rahman Sufi called "Sour al-Kawakb" is one of the scientific masterpieces of astronomy of the Islamic period, which he wrote in the fourth century of Hijra under the aliasAzd al-Dawlah. ” Sur al-Kawakb” by Abd al-Rahman Sufi is one of the treatises on astronomical sciences of the Islamic period, which was very important in the history of astronomy. This book has been illustrated by artists in different epochs of painting history. In this study, we delve into the illustrated versions of Abd al-Rahman Sufi's constellations from the 6th, 9th, and 12th centuries AH, scrutinizing constellation types, image structure analysis, decorative elements, disparities, and commonalities.In order to analyze the twelve zodiac signs, indicators include visual elements in the image, visual elements in the text, the type of space creation (location of the role), the emphasis element in the image, the type and quality of the frame, the dominant element in the illustrated page, the characteristics and the way the image is executed, as well as the way it is represented. The image in the twelve signs was examined in three versions. Therefore, in response to the research questions, the results show that one of the common visual features in all three versions is the use of the line element in the representation of images in such a way that in all three versions, the quality and speed and slowness of the line and its use in showing depth. This attribute is most prominent in the second version (Metropolitan). Another visual aspect involves the frame's role in visualizing the subject. Artists accorded the frame a distinct role in illustration.Although in some pages the frame has the conventional shape, the artists imbued the image with a sense of breaking free from the frame, aligning with contemporary painting attributes. This feature is observable in selected illustrated pages in both the second and third editions.Color tones also constitute a visual feature across all versions. Notably, the second version's crab depictions employ unconventional colors, including blue. In addition to this, the visual artists have also paid attention to three versions of the texture to show the mane and the end of the tail in the images of Burj AsadIn summation, In version number one, the twelve-fold sign is the dominant visual element of the line compared to the other two versions. The type of space creation is associated with the combination of text and image, which is formed in the pages related to towers with the dominance of the image in the upper or lower half of the composition page. In the second version, similar to its counterparts, the emphasis centers on the line element, utilized by painters to imbue volume. In this version, unlike the other two versions, the page is dominated by the image and has no frame. The text in this version is limited to a small frame and often drawn at the top of the page. The dominant color is brown, and gold is used to show the position of the stars, and the circles are surrounded by red. The illustration of this version is realistic in showing animals and unrealistic in showing human figures. In the third edition, distinct from the other two, color serves to dimension and adorn body parts, clothing, textures, and other image elements. This version, like the first version, has a frame, its characteristic feature is that the image elements are broken and overflowing from the frame. Despite the image's prominence, writing complements the version, aligning closer with nature and reality compared to the preceding editions. While some frames maintain their traditional appearance, artists purposefully allow images to overflow the frame, coupling text and image to create spatial compositions, particularly evident in pages linked to towers.

Keywords: Constellations, kitāb suwar al-kawākib, Abdul Rahman Sufi, Stronomy, Iranian Painting -

Pages 40-57

Introduction The term "emoji" is an anglicized adaptation of the Japanese words "e" (meaning "picture") and "moji" (meaning "letter" or "character"). So, the definition of emoji is, simply, a “picture-word” accurately encapsulating its essence.. The primary function of an emoji is to fill in emotional cues otherwise missing from typed conversation. Emoji exist in various genres, including facial expressions, common objects, places, types of weather, and animals. Emojis are standardized pictographs used to emphasize the emotional tone of the message, indicate emotions, open conversations, and convey the mental state of the message sender While emojis are a cornerstone of social network interactions, their influence extends to other domains, such as culture and commerce..Nowadays, emojis are used in commercial ads, consumer goods, cultural productions, computer games, animations, etc. Therefore, they have a much broader application scope besides social networks. The global obsession with these images, their recurrent use in everyday life, and their positive role in communication have turned these symbols into common and familiar tools for everyone. Emojis have also been applied to contemporary art. The incorporation of these images in visual arts might be explained by recent inclinations of contemporary art and the use of clichés in works of art (especially in pop and neo-pop art). Thus, if we take the “emoji lexicon” on social networks as a “cultural-visual” text, then the use of emojis in other areas might be considered a form of (direct or indirect) imitation from this lexicon. This study seeks to investigate the incorporation of emojis in contemporary art and explore the possibility of creating parodies using Linda Hutcheon's framework on parody. Specifically, it aims to address the following questions: How are emojis integrated into contemporary art? How do artists imitate emojis within the realm of visual arts? Can the adaptation of emojis from their cultural context into the realm of art, along with their imitation, give rise to an ironic situation or parody?The objective of the present study is to analyze the application of emojis to contemporary art to create parodies using Linda Hutcheon’s “A Theory of Parody”. The present study was done with the objective of fundamental research using the descriptive-analytic method. Qualitative data analysis was used in conducting the research. Data were collected using library and digital resources. The research population consisted of works of art that used emojis. Eight out of ten works of art were selected as samples. Linda Hutcheon’s “A Theory of Parody” was used to analyze the works of art. Linda Hutcheon is known as one of the most prominent postmodern researchers and theoreticians. The postmodernism of Hutcheon is deeply linked with intertextuality and parody. Parody is considered one of the oldest forms or sub-forms of art which entails intertextuality. Postmodernism pays special attention to parody. Parody is defined as making (conscious) or ironic use of another (often, not necessarily) art pattern. In semiotics, parody is defined as a humorous representation of a literary text or a work of art. In other words, it is the representation of a “modelled reality” that is itself a representation of an “original” reality. In her book “A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of the Twentieth Century Art Forms”, Hutcheon defines parody and its function, its similarity to other (literary and art) genres, coding and decoding, the importance of the codes embedded in the text and their interpretation by the reader. According to Hutcheon, parody is repetition, but repetition with a difference, imitation with critical ironic distance. Parody uses irony as the main tool to signify or even create contrast. Therefore, exploring whether imitation contains an ironic situation or not is an important marker in identifying parody (from Hutcheon’s point of view). Thus, the first element to analyze in a work of art is its ironic edge. As mentioned before, it is the ironic edge of a parody that helps create distance from the original text and imitation alone does not create a difference. Hutcheon also argues that to understand what a parody is. we should consider the entire act of enunciation, production, and context of reception about a text. She uses the word “ethos” to explain this concept. According to Hutcheon, ethos is a feeling conveyed to the decoder by the encoder. The ethos of a parody might range from respectful, neutral, or playful to mocking and ridiculing. Therefore, the degree to which an (artistic) text is parodic might depend on the extension (intensity) of its ironic edge. According to Hutcheon, parody is not just a humorous imitation, but a broad range of ethos. Thus, the intensity of the parody is another element to analyze in a work of art to recognize how each work alters the original cultural text (emojis). The third element to consider in Hutcheon’s theory is the importance of encoding and decoding a parody. Hutcheon refers to the importance of encoding the signs embedded in the text and interpreting them. In encoding a text as a parody, the author (encoder/artist) should consider a group of shared cultural and linguistic codes and the reader’s familiarity with the parodied original text. Just like irony, parody demands embedding a certain group of aesthetic and social (ideological) values in the text to enable comprehension. Thus, to analyze a work of art, one must pay attention to the author’s encoding and the codes they place in the work (in a text with a familiar culture, codes might be embedded in social and cultural discourses and even emojis) and also the reader’s decoding based on their cultural and artistic background and familiarity with the codes embedded in the text. Regarding the objective of the present study and essential elements used in creating a parody from Hutcheon’s point of view, eight visual works of art that applied emojis were analyzed. The results of the study showed that conveying emojis from the cultural context of the “emoji lexicon” into the work of art and altering its sign system and medium could itself create an ironic edge since emojis are used to open conversations and convey the sender’s message tone, feelings, and mental state. Although emojis are humorous and playful, they lack an ironic or critical edge and often refer to what they signify. Therefore, they lose their communicational function by moving to another medium , they can refer to what they signify but they lose their previous function. In the artistic setting, they both legitimize the original cultural text and include critical distancing. In addition to this, each work uses a special method to create an ironic situation. The second point in Hutcheon’s theory is the function, ethos, and intensity of the parody which is directly linked to the ironic edge and ranges from respectful, neutral, and playful ethos to a ridiculing one. The parody created from the analyzed works of art has a double relationship with the original text. This relationship is humorous, amusing, neutral, or playful, but not ridiculing or destructive at all. However, the parody keeps its ironic distance from the original text. Finally, the encoding and decoding of each work of art were analyzed. From Hutcheon’s point of view, the first condition is the reader’s familiarity with the original text. She believes the encoder (artist) embeds a group of aesthetic, cultural, social, and ideological codes in his/her work and the decoder can only understand the parody by identifying them. The three main elements in Hutcheon’s theory apply to these works and the artists have used different methods to create parody. The results showed that the artworks had ironic elements,a prerequisite to parody in Linda Hutcheon’s views, and the resulting parodies have a double-edged relationship . They have an affirmative tone while maintaining an ironic distance. Also, it would seem that due to the diverse encoding methods applied to the artworks, most of them have recognizable pictures and socio-cultural elements that the common people can easily understand which makes the decoding process much easier.

Keywords: Linda Hutcheon, Parody, irony, emoji, Contemporary Art -

Pages 58-71

Traditional design encompasses the artistic practice of creating Slimi and khatai on spirals and sporadic arches. From this perspective, these motifs can be interpreted as symbolic expressions, akin to words embedded within the paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes to serve the purpose of storytelling. These motifs hold a dual significance with respect to both form and meaning. In this manner, the narrative elements that require pairing to convey coherence are substituted with pivotal concepts. These visual symbols resemble sentences formed by merging words along the horizontal axis, facilitated by their meaningful arrangement along spiral connections. The interplay between these dispersed motifs across the overall composition contributes to the establishment of overt and implied narrative meaning. It is crucial to focus on the cultural context as the shared origin of representation and content. Recognizing its significance within the design context is connected to the selection of content and its alignment with representation. In fact, neglecting this importance in the research context of Iranian traditional design art in general and the art of carpet design, in particular, is one of the issues that requires research. Focusing on the semantic dimension of motifs elevates them from mere decorative forms to forms that generate narratives and meanings.The "Bashariat" carpet, designed by Issa Bahadri, offers an opportunity to investigate the realization of the aforementioned attributes. The Khataei and Slimi motifs designed in its context deal with the hidden depiction of human figures, which in meaningful interaction, narrate the story of the origin and continuation of the human race. In other words, the "Bashariat" carpet within the context of a general image system is the convergence point for two distinct histories – one mythological and the other religious – visually intertwined at the core of its backdrop motifs. To comprehensively analyze this aspect, employing a methodology aligned with narrative analysis subjects, such as Roland Barthes' narrative codes, proves essential. According to these connections, the narrative doesn't have a preset meaning; instead, it has a interconnected structure made up of five codes. Understanding these codes is imperative for grasping Barthes' delineation of the narrative's author and reader roles. Although the words for writing are available to all authors in the same way, in his opinion, what makes them stand out is the way these words are employed in the narration. When a writer writes with passion at the helm, they produce significant texts, and their readers transform into writer-readers who revise the texts on the precipice of reading and writing as they read. The significance is further exemplified by the carpet designer of "Bashariat," who, despite drawing inspiration from customary patterns, sought innovative and meaningful representationHermeneutic and action codes, which have a horizontal relationship in the syntagmatic axis, are seen to be the causes of the development of the story. The story is created by merging the other three codes, which likewise point the reader to associated semantic bases outside of the text and have vertical relations in the paradigmatic axis. An important point in this field is the lack of researches that have studied the traditional design from the perspective of narrative codes. The current study adopts a descriptive-analytical methodology to address the question: "What are the meaningful interpretations of motifs within the narrative of the 'Bashariat' carpet based on Barthes' narrative codes?" In this sense, just the text portion was examined, based on the significance of the topic of mankind and the creation story from the standpoint of narrative ciphers. This significance highlighted the need for human themes in the visual interpretation of this tale, and its lack in the carpet's margin precluded the study of the margin from considering the research process. The findings of this study demonstrate that, in addition to serving their primary purpose of adorning and beautifying the carpet's surface, the visual elements created for the carpet of Bashariat also took into account the two elements of narration and meaning generation, which are divided into five codes as follows:-The hermeneutic coder investigates the Khatai motifs of Toranj and Slimi of Lakh from the perspective of the concepts contained in human motifs and the meaningful relationships coming from the arrangement of motifs of men, women, and children. This is done by challenging the text's unity. The solution to it pierces the second theme region, which has its roots in a mythical account of how early humans first came into contact with plants. According to mythology, Mesh, and Mishyaneh, the first human parents, were born from Gyumerth's discarded sperm and enhanced Urmuzd's excellent creation by bearing offspring. The human figures tucked away in the center of Taranj's khatai patterns, whose unity symbolizes the continuance of the human race, can be considered as the visual representation of this idea. However, in accordance with Islamic doctrine, the first birth's beginning point is related to descent. The human body created in Lakh in an abandoned state is an example of the fall, and its decline has been the cornerstone of Bashariat that marked the beginning of the human race in Toranj. - In accordance with the text's fundamental meaning, the man, female, and rooster characters' sequential acts provide the context for the action symbols. The word Bashariat is written in the Toranj region by two men, holding the word firmly in their hands to act as a guardian. Next is the representation of a woman's living head, corresponding to the mythical ideas about women's bodies being healthy and ensuring reproduction. A body covered in flowers and the pattern of two blossoming flowers in a woman's maternal body are manifestations of this health. When it comes to ensuring that the generation continues, these traits complement the active action of the woman and the protective action of the male. In the setting, the rooster's ultimate stance, in which it is flying toward the infant, serves as a protective function, and it symbolizes the rooster's mythical and religious significance.- The upward reading of Toranj's design, ascending from bottom to top, considers Islamic discourses that prioritize male origin in the creation of humankind. The positioning of the male figure as Adam at the bottom of the female body symbolizes this hierarchy. The dynamic interplay of stillness and movement between the male's horizontal posture and the female's vertical placement signifies complementarity. The spiral arcs on the carpet's background, rising from under Adam's hand, convey both humanity's perfection post-fall and additional connotations.- The child's form, arising from the convergence of male and female forces, bears symbolic meaning. Resembling his father in posture, hair color, and appearance, he embodies Zoroastrian principles. Although there is no difference between having a boy or a girl, documented records indicate that boys are preferred over girls. A single body is another sign with a two-way reference to descent in the elastic portion. According to the theories of ancient Iran, he is evocative of Gyumerth because, as a human prototype, he creates a common appearance among people without gender distinctions. He has a fluid condition and is devoid of gender signals. The second case could represent Meshi and Meshianeh, who split off after succumbing to Satan's temptation and were created from Gyumerth's pure sperm in the shape of a rhubarb plant. In contrast to this design element, the background of the carpet has snail and rooster motifs, which symbolize male and female genders.-The dual notions of ancient Iran and the Islamic faith in the carpet of "Bashariat" are realized as cultural symbols that have an impact on all symbols. As a result, human themes have evolved into pairs in mythical and religious narratives, such as "Mashi and Mashianeh" and "Adam and Eve," or they have taken on symbolic dual meanings, like snail and rooster motifs. However, the focus on the idea of couplehood that has been achieved in the general design of the carpet with the 1/2 pattern is crucial to the consensus of these ideas. As a result, while depicting male and female couples and the idea of their complementarity in producing a pair of occurrences in one half of the carpet, it also deals with their multiplication in the second half, which highlights multiple marriages.

Keywords: Traditional Drawing, Isa Bahadori, Bashariat Carpet, Narrative, Roland Barthes' Five Narrative Codes -

Pages 72-92

Blacksmithing entails the transformation of metal to craft iron tools. Historically, the crafting of metal goods fell under the domain of Chelengar. This entity prepared the primary substrate of the metal for pattern acceptance and Zomudgari. Skilled craftsmen then etched patterns and inscriptions onto the metal. Literally, Zamud also conveys the addition of ornamental roles and components. Essentially, Chalangar and Zamudgar collaborated closely in construction endeavors. With the emergence of iron doors and windows, this practice has evolved to embellish windows and entrances of distinctive locales. Within the traditional framework of ancient trades and vocations, blacksmiths ranked among artisans who forged iron in furnaces, shaping metal components into diverse tools through a process of hammering. Chalengari, a branch of blacksmithing, also referred to as small blacksmithing, stands out. Nevertheless, due to industrialization affecting numerous metal structures, this artistic pursuit has faded from memory. In yesteryears, it showcased the aesthetic sensibilities of Iranian instrument makers in various forms, embodying cultural expressions and reflecting elements of Iranian identity. Notably, the initial aspect captivating artists within households was the entryway's view - encompassing doors and windows. During the second Pahlavi era in Tehran, structures boasted splendid window railings and doors adorned with assorted designs, highlighting the artistry of Tehrani blacksmiths. From the era of Qajar monarchs, statesmen, and intellectuals, fascination with major European metropolises grew. Western advancements in modernity captivated attention. This phase witnessed changes that retained national identity and upheld traditions. However, during the Pahlavi era, an ideology promoting the replacement of the old by the new gained ascendancy in Iran. Consequently, there exists a need to engage in research to revive the art of changari, shedding light on the motifs, techniques, and forms employed in these fences, windows, and doors. What constitutes the methodology underlying the design, construction, and technique of Chelengari (windows and doors) blacksmithing in Tehran, along with their motifs? The research approach is descriptive-analytical, employing information collection from libraries and the field. A total of 900 windows and doors were amassed, analyzed, and scrutinized. Findings reveal that design methods are characterized by simplicity and abstractness, involving semi-abstract renderings. Symmetry motifs are dispersed through single, analogous (one-second, one-fourth), and contiguous (4*1, 4*3, 2*3, 4*4, 2*6, 4*6, 3*1, 3*2) patterns. Construction techniques involve transcribing desired designs onto estimating pages. Subsequently, utilizing metal straps measuring 2 cm in width and 0.5 cm in diameter, or at times iron sheets, craftsmen prepare and affix motifs onto door and window frames. These motifs can be categorized as abstract, comprising human, animal, plant, geometric, and Chinese knot themes. The diversity of design, developmental processes, and motifs in Chelengari blacksmithing during this era draw inspiration from Iranian knot motifs found in brick, wood, and particularly tiling. Abstract paintings of 19th-century schools (Suprematism, revisionism, constructivism) further influence these motifs, intertwining with prevailing motifs of Iranian modernity. Throughout this span, Chelengaris exhibit a fusion of Iranian-European roots, with all patterns and forms harmonizing with door and window dimensions and shapes. Moreover, the inception of window railings, door guards, and balcony protections in Tehran dates back to the Qajar period. This trend persisted through subsequent architectural epochs, particularly the first and second Pahlavi periods, resulting in progress and evolution within railing-window and door-balcony protection construction. However, this trend witnessed a decline during the latter Pahlavi era, sparking significant alterations in design and pattern dissemination. Commencing in the Qajar period, Chelengris embodied elements of embellishment, privacy, and security. Over time, especially in the second Pahlavi era, their decorative aspect gained prominence. The infusion of Western architectural influences, coupled with heightened external engagement, showmanship, and an emphasis on facades and urban exteriors, became noticeable since the Qajar era. This era also marked increased interaction between Tehran's populace and other cities and nations, infusing urban environments with vibrancy and fostering outward-looking perspectives. The evolution of these metal barriers adorning windows underwent substantial change from the Qajar era to the second Pahlavi period. Essentially window guards, these installations served both protective and decorative roles after exterior windows were put in place, transforming cityscapes. These transformations were driven by factors such as Western advancements across various domains, expanded trade, the transformative effects of the constitutional movement on social structures, and the migration of craftsmen to neighboring countries like the Caucasus. Notably, interactions with foreign societies, the rise of unions and guilds, the movement of businesspeople and intellectuals abroad, and exposure to new cultural and social content further contributed to these shifts. This period also witnessed the arrival of modernization in Iran as the nation faced new neighbors in England and Tsarist Russia, prompting a confrontation with Western influences. The introduction of modern materials like rebar, beams, and cement for factory, bridge, and railway construction, alongside the dissemination of drawings, postcards, and photographs, further fueled these shifts. Modernization was fostered by factors such as the constitutional movement, sending students abroad for education, translations of foreign texts, and the influence of Western architects' works. These developments deeply impacted Iranian life across literature, poetry, and the arts, ultimately resulting in a departure from traditional forms, the adoption of Western architectural styles, and a fusion of global features with native Iranian architectural concepts. Conclusively, the architecture of the Pahlavi period drew from late Qajar architecture, modernism, and neoclassical archaism (nationalism). During the second Pahlavi era, architecture seamlessly aligned with modern architectural paradigms. This period saw an attempt to merge native Iranian architectural elements with global modern features to create structures universally resonant across diverse cultures and races.

Keywords: Blacksmithing(Chelengari), Door-window, Architecture, Tehran, Pahlavi II -

Pages 93-105

The dynamic relationship between culture and art influences both domains significantly. Within various cultures, the adoption of decorative patterns holds particular significance. The selection and evolution of decorative patterns are influenced by each culture's context. Historical artifacts reveal that geometric decorations have long played a central role in human culture, undergoing progressive development over time. A subfield of geometry known as "Girehes" has extensively permeated Iranian-Islamic architecture, directly influencing its aesthetic foundation. The realm of Girehes intertwines mathematics and aesthetics, originating from a context of robust mathematical inquiry. Although historical records are scarce, they suggest that adept practitioners of practical geometry orchestrated the design of Girehes found on historical monuments. However, these designers rarely sought to establish a purely mathematical or theoretical basis for their designs.Gireh's principles, rooted in mathematical foundations, have captivated contemporary researchers worldwide, owing to their mathematical underpinnings. Surprisingly, adherence to geometric and mathematical principles has not stifled the diversity within design and structure. On the contrary, artists during the Islamic era expanded the scope of geometric patterns with remarkable diversity. Notably, one prominent classification system within Girehes revolves around their respective families. This taxonomy encompasses Acute, Median, Obtuse, and Two-point categories, based on the angle formed by the lines of the "Shamseh," a central motif that reverberates across the entire Gireh design.However, it's noteworthy that not all Girehes adhere to a specific angle formed by the Shamseh lines. Nevertheless, a substantial majority of researchers tend to rely on a categorization hinging on angles of 36 degrees (Acute), 72 degrees (Median), 108 degrees (Obtuse), and Two-point, due to their prevalence. It's essential to recognize that the angles attributed to Gireh families are not universally applicable. Variations include Girehes featuring angles of 30°, 60°, 90°, and Two-point, or angles of 45°, 90°, 135°, and Two-point.To address questions surrounding the diverse angles between star lines leading to Gireh classification into various pattern families and the structural rationale behind the modular arrangement of angles within these families, this study employs a descriptive-analytical approach. It leverages library resources to delve into the structure of six-, eight-, ten-, and twelve-point Girehes, aiming to unveil the geometric underpinnings of Gireh families and the correlation between angles in different families and the Girehes' structures.Girehes, part of the Islamic artistic tradition, comprise tessellations formed by regular geometric shapes harmoniously arranged to maintain uniformity. Known as "Gireh-Work," this form of geometric decoration often juxtaposes the "Shamseh" motif with polygonal elements to create a balanced composition. Traditional masters and modern research corroborate the notion that Gireh hinges upon a harmonious interplay of components. This interplay, however, is not arbitrary; beneath the Gireh motifs lies a concealed layer, termed the "underlying generative tessellation," elucidating the overall order of Gireh compositions. This generative tessellation forms the basis for drawing Girehes, allowing the placement of various Gireh motifs. Given Shamseh's critical role, artists and masters assign diverse names to it based on the number of Shamseh points. This motif profoundly impacts the overall design, shaping its structure. The foundational stars of Gireh often stem from this process, frequently defined by the connection of midpoints in the underlying polygons, which in turn determines pattern lines.Shamseh's significance extends beyond the individual motif to dictate the broader Gireh structure symbolically. Consequently, the angle of the Shamseh influences all Gireh motifs and determines their respective families. Three main categories of classification emerge based on the points' arrangement, encompassing eight-pointed, six- or twelve-pointed, and ten-pointed Girehes. Classification by Shamseh angles yields four categories: Acute, Median, Obtuse, and Two-point. In earlier times, artists relied on drawing rules grounded in circle divisions, lacking modern tools to measure line angles accurately. Consequently, Gireh angles were often determined through methods aligned with the number of Shamseh feathers or multiples thereof.The connection between Shamseh points and Gireh's structure is profound; assuming a Shamseh point count corresponds to a radial division of the circle, the number of Shamseh points shapes the angle structure of the entire pattern family. With α and β representing the angles of Shamseh lines, and P denoting the number of divisions in the pattern family, while F signifies the division number modulus in the Gireh family, the relationship can be expressed as follows:α = β = F/P × 360° = A°This circle division modulation closely corresponds with the fundamental polygons of Girehs. Classification of Gireh families rests on the base polygon, relying on connections of line segments between points on the polygon's sides. Regular polygons can be circumscribed within a circle, aligning the modularization of node families with radial divisions. This arrangement is evident in six-, eight-, ten-, and twelve-point Girehs. If the modularization equals the distance of one unit from the middle points in the base polygon, it's classified as Acute. Similarly, if the distance equals two units, it's Median. For a three-unit gap, it's considered Obtuse. Finally, the placement of Gireh lines at 1/4 of the polygon's sides or vertices, instead of the middle point, signifies the Two-point family.Evidence of Gireh's historical reliance on polygon techniques is further demonstrated by the alignment of angles in Gireh families with the angles formed by lines at the polygons' midpoints. Gireh designers effectively harnessed polygons' geometric structure to craft intricate Gireh patterns within an encompassing framework known as the underlying generative tessellation. The division of the circle directly corresponds to the base polygon's grid system. The number of fold divisions dictates the base polygon's sides – a 12-fold division corresponds to a dodecagon, a 10-fold division to a decagon, and an 8-fold division to an octagon. Acute, Median, and Obtuse families are harmoniously woven using lines connecting midpoints in the primary polygon through a generative tessellation. Correspondingly, the Two-point family neatly aligns with the polygonal structure, deviating from the middle point to formulate patterns based on distances from middle points to vertices.

Keywords: Gireh, Generative tessellation, Acute, Median, Obtuse, Two-point -

Pages 106-123

Post-modernism, both in theory and in art, is faced with a disappearance of meaning and imponderable situation, and anti-determinism and uncertainty as its main motives. Jean Baudrillard (1929-2006) as one of the most influential theorists and critics of post-modernism, has put his main focus on the criticism of new communication media, the meaninglessness of icons and debates such as hyper-reality and loss of reality.. He stands out as a prominent contemporary thinker and a controversial writer in the fields of literary theories, semiotics, sociology, and postmodernism criticism. Baudrillard contended that contemporary icons had lost their fixed values and natural significance, emphasizing their profound meaninglessness in numerous works, such as "System of Objects" (1968), "Toward the Political Economy of Icons" (1972), where he evaluated, criticized, and raised doubts about Marx's economic theory Baudrillard's provocativewritings in the 70s and 80s of the 20th century, such as Consumer Society[1] (1970), Simulacra and Simulation [1] (1981), In the Shadow of the Silent Majority[1] (1978) have obtained for him a special place in scientific and literary societies. His collection of articles related to the Persian Gulf War in 1991, which was published under the title The Gulf War Did Not Happen[1], garnered widespread attention, discussion, and criticism.Baudrillard's somewhat exaggerated opinions contained controversial messages such as the loss of reality, which eventually led to the emergence of a new concept called hyperreality.In the 70s and 80s of the last century, he claimed that we live in the age of simulations. This starts from the growth and expansion of information technologies, including computers and virtual media. Baudrillard clearly claims that in today's era, meaning tends to vanish within the realm of communication.This research endeavors to analyze various postmodern artworks and compare them with Jean Baudrillard's perspectives on the definitions of "meaning" and "reality," seeking a deeper understanding of the conceptual layers of postmodern art.The research method is descriptive-analytical, which is carried out with an inferential approach, , and falls into the category of basic research in terms of its purpose. The method of collecting information is based on written library documents and internet sources. A case study including works by seven artists (Liu Bolin, Duane Hanson, Don Eddy, Nam June Paik, Leopoldo Maler, Benjamin Edwards and David Hockney), which are clear examples to explain Baudrillard's ideas about the loss of meaning and Reality in the field of visual arts.The research questions are:How do features of postmodern thought, such as the vanishing of meaning and the loss of reality, manifest in contemporary visual arts and through what media?In light of the prevalence of virtual reality and the clash between reality and imagery, what transformations have visual arts undergone?Drawing on Baudrillard's views on meaning and reality, how can contemporary artworks be interpreted?Chinese artist Liu Bolin (born in 1973) has created works that may be difficult to place in a specific art group. The mentioned works can be considered a perfect combination of painting, sculpture, photography, body art and performance arts. The artist has publicly reflected the cultural policies of the Chinese communist government and the transmutations of individuality in social interests in his works. Bolin, who is also known as the "invisible man", chooses the body of a living human being as the main substrate of the work of art. By meticulously camouflaging these individuals to blend seamlessly with their surroundings, he creates visual illusions that convey the complete transformation and disappearance of reality. Baudrillard's terms such as the disappearance of meaning, the disappearance of reality, simulacrums to replace reality, etc., are visually expressed in Bolein's works. Another discussed work is “Woman with Shopping Basket” by Duane Hanson. Although this work shows the reality of urban life in America at first glance, it actually challenges it with a critical view by its over statement. What Hanson does in this work is to show the complete set of mentality of the American consumer society.Baudrillard mentions that in the consumer society the value of "being" means the sacrifice of economic values. Abundance only finds meaning in extravagance. For abundance to become value, "enough" must give way to "too much".Therefore, it can be said that this extravagance is present in all aspects of today's life, and reality is not exempt from this pattern, and extravagance in reality or in other words, abundance in reality is also evident. On the other hand, hyperrealism itself shows a state of abundance of reality.The next work belongs to Don Eddy. While the subject of the work is familiar and general, it shows a complex and overlapping scene of a shop window. In his works, Eddy tries to show the relationship between man and space in an enigmatic, complex and multiple way by mixing up visual plans. By creating the illusion of reality, he creates a space in his works that bring a multifaceted and poly hedral experience of the contemporary confused reality to come into existence. Eddy's works can be considered as a hyper-reality, which tries to show a deeper meaning than reality. The next one is TV Buddha, by Paik, a statue of a thinking and mesmerized Buddha in front of a television box. It aims at demonstrating the dominance of today's media over ancient beliefs, as well as the conflict between religion and technology.The statue stares at its virtual image, as if it is deep in thought. Virtual space offers a new definition of Buddha to himself. In this work, the artist presents a new definitions of the boundary between reality and the tropologic and cultural confrontation by contrasting Eastern religious thinking and the Western technological world. The next discussed work is “ The Death Sequence“ by Leopoldo Malerwhich reflects the duality and conflict between reality and image andevokes Baudrillard's ideas about the power of image over reality in the system of simulacrum. A nurse is sitting next to a bed that holds the image of a corpse. The work represents a reality: decomposition on different levels. In this way, the image is in the main focus of the subject and the reality is placed in its margin, just as death is prioritized over life. To understand the concepts of instability of meaning and plural space, we can refer to the creative experiences of Hockney's photographs and Edwards' paintings.In Edwards' works, the experience of ruptured space and elongated time within the genre of landscape painting produces a surreal effect more pronounced than in other painting genres. His landscapes create multifaceted spatiotemporal intervals that underscore the instability of meaning and the ephemeral nature of events .Baudrillard engaged with the subject of postmodern art personally and left significant writings in this field.Post-modern artists have created works influenced by intellectual currents, including Baudrillard's critical thoughts. By comparing the works of the mentioned artists with the thoughts of Jean Baudrillard, we exclude the commonalities between theory and practice in the postmodern era in a deeper way. Discussions such as the disappearance of meaning and the loss of reality in Bolin's mixed art, hyper-reality in the works of Hanson and Eddy, the omnipresence of virtual space in Paik's works, and the conflict between reality and image and the substitution of simulacrum for reality in the work of Maler, as well as The plural space in the works of Edwards and Hockney all confirm the disappearance of meaning and the loss of reality in contemporary thought and practically show the link between theory and practice in examples of post-modern art.

Keywords: Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra, Lost meaning, Hyper-reality, End of reality, Contemporary Art -

Pages 124-142

After the triumph of Islamic revolution, the paradigm of modernism, which had previously dominated the Iranian art scene under the Pahlavi regime, underwent a radical shift. Traditional Iranian arts, including Iranian painting (Miniature), were now regarded as emblematic of contemporary Iranian art. The discursive signifiers of revolutionary art were the challenge between Traditional Iranian art and the Western art, as well as the intricate interplay between artistic form and meaning. This revolutionary art endeavored to craft a new form of contemporary Iranian art aligned with Iranian-Islamic culture. Amidst the ongoing discourse between modernist and traditional art, the terms "modernism," "traditionalism," and "neo-traditionalism" surfaced. Simultaneously, the fundamentals of religious arts were elucidated and articulated for artists in response to the exigencies of the contemporary era. Thus, this positioning of religious arts laid the groundworks for art journals and institutions to consider painting as the means of investigating the identity of contemporary art.The concept of "modernism" in traditional painting, miniature in particular, was so legitimized during the post-revolution traditionalism paradigm that it implied the adoption of a contemporary lexicon to interact with the audience of revolutionary art in Iran and the world.Traditionalist publications, conscious of revitalizing Iranian artistic traditions, directed a special spotlight on Iranian painting (miniature). By referencing Islamic painting's cultural and artistic heritage, these magazines sought to formulate a novel language of expression rooted in the revolutionary art movement. Conversely, magazines aligned with "modernism" paradigm considered traditional arts, including Iranian painting, belonging to the glorious past, and not to the contemporary era.This paper aims to describe the concept of contemporary Iranian painting in the contents of 12 specialized artistic or cultural-literary journals: Faslname Honar, Keyhane Farhangi, Soure, Honare Moaser, Honarhaye Tajassomi, Binab, Tandis, Golstane Honar, Adabestane Farhang & Honar, Kelk, Adineh & Donyaye Sokhan. The research endeavors to address the following query: How has the portrayal of contemporary Iranian painting been constructed within post-Islamic revolution cultural-artistic journals? Reviewing the data from selected texts, this study extracts and analyzes the recurring themes related to Iranian painting across these twelve journals published over approximately three decades (1981-2013) post the Islamic revolution.This issue is important for understanding the current situation of the Iranian painting as a cultural asset and to achieve its contemporary language.In this research, the data has been purposefully collected and analyzed by thematic analysis method through the study of documents that have played a role in the construction of the image of miniature in the Iranian post-revolution art.The theoretical framework of this research draws from theories concerning the contemporaneity of art. "Contemporary" is a concept contingent upon temporal definitions, each shaping a unique interpretation of contemporaneity. Philosophical perspectives on "contemporaneity" inform the understanding of contemporary miniature painting within the modernity and postmodernity intellectual paradigms.According to Kandinsky, every art work is a child of its "time" and every cultural era creates its own special art which is unrepeatable. From his viewpoint, time and place are considered two outstanding factors in determining the artist's relationship with contemporaneity, which ends to a structure in artistic style to distinguish any art era from other eras, based on the "artist's point of view".The findings of this research underscore that the concern for "identity and contemporaneity" within post-Islamic revolution Iranian painting engaged intellectual discussions in cultural-artistic journals, resulting in a spectrum of perspectives. These viewpoints range from considering contemporary miniature as an eternal art rooted in historical truths to perceiving it as belonging to a bygone civilization incongruent with the "modern" epoch.These Diverse ideas fluctuate from the two points of view; one concerning this art eternal, and the other considering it as dedicated to a vanished civilization. The study unveils the existence of diverse constructions of contemporary Iranian painting across three paradigms: "traditionalism," "neo-traditionalism," and "modernism." The prevalent global language of art and the prevailing zeitgeist influenced the distinct images crafted within each paradigm. While modernism and neo-traditionalism conceive contemporary arts as reflective of the modern era, traditionalist magazines position contemporary miniature painting within the context of globalized contemporary art.The analysis of themes in this article showed that the nature and identity of Iran's contemporary painting and its perspective in 6 specialized art magazines " Faslname Honar, Honare Moaser, Honarhaye Tajassomi, Tandis Golstane Honar,and Adabestane Farhang & Honar" and 6 art-cultural magazines "Keyhane Farhangi, Soure, Binab, Kelk, Adineh and Donyaye Sokhan " is ambiguous.As a result, different ideas of contemporary Iranian painting were constructed out of 3 paradigms: "traditionalism, neo-traditionalism and modernism", which are different in each paradigm according to its view to universal language of art, era and time.In the modernism and neo-traditionalism paradigms, which contemporary arts are "modern-day" arts, it seems that the idea of contemporary miniature was embodied in an image that became homogenous with the dominant art of this era - that is, the modern and postmodern art of the West.Honare Moaser, Honarhaye Tajassomi, Tandis, Adabestane Farhang & Honar, Kelk, Adineh & Donyaye Sokhan journals, by considering the traditional principles of this art, described its contemporaneity in accordance with globalized contemporary art.On the other hand, by adopting a theoretical approach, the magazines inclined to the traditionalism paradigm, based on the belief in eternal time and the stream of the remaining time in various historical eras, including the current era, formed the concept of contemporary miniature in a distinct image. By referring to the trans- temporal truth of miniature and the discovery of its forgotten language, it is possible to create a language could communicate to art of the world based on the "trans temporal-eternal" nature of this art.Faslname Honar, Keyhane Farhangi, Golstane Honar, Soure and Binab journals have been more aligned with this theoretical approach.In a general view, constructing a coherent image of contemporary miniature was not formed in any of the two mentioned approaches. The clash of opinions in this regard did not approach to a specific direction. one reason is the gradual decrease in the publication of specialized non-academic cultural-artistic journals, as a mean for elite thinking to raise fundamental questions concerning the identity of Iranian contemporary art and exploring to find their answers.

Keywords: Iranian painting, Contemporariness, Artistic Journals, Traditionalism, Modernism