فهرست مطالب

مجله منظر

پیاپی 33 (زمستان 1394)

- تاریخ انتشار: 1394/11/11

- تعداد عناوین: 13

-

-

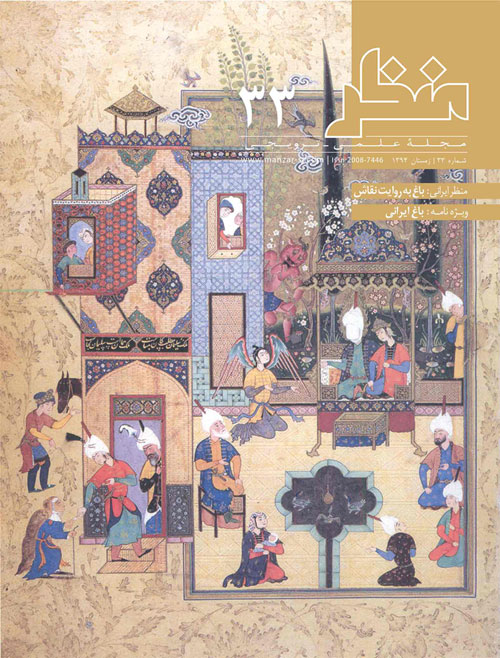

باغ به روایت نقاشصفحه 3

-

صفحات 6-13هنر باغسازی ایرانی، محصولی از فرهنگ و تمدن ایرانیان است که عناصر و اصول آن به اندازه کافی شناخته نشده است. غیر از خیابان اصلی یا جوی آب روان، باغ ایرانی از عناصری تشکیل می شود که باید هویت و نقش آن ها در ایجاد مفهوم باغ بازشناسی شود. دیوار محوطه، که در همه نمونه های اصیل باغ ایرانی تکرار می شود، از آن دست عناصری است که میان ساده اندیشی عملکردی با پیچیدگی فرهنگی نمادین سرگردان است. مطالعه دیوار به مثابه یک «پدیدار» تا حدی از اسرار ماهیت و نقش آن در تولید سبک باغ ایرانی رمزگشایی می کند. دیوار، عنصری چند مفهومی است که به کارگیری آن برای محصور کردن باغ، فارغ از فواید کارکردی آن، نقش ارزنده ای در ایجاد معنا و هویت ایرانی باغ دارد؛ چه، باغ ایرانی عرصه ای برای تامل در طبیعت و نظر بر آیات هستی است. این عرصه با توجه به خصوصیات ذهن مخاطب و ظرفیت های منظر (و فضا) نیاز به رعایت آداب خاصی دارد که دیوار از زمره مهم ترین آن هاست.کلیدواژگان: دیوار، باغ ایرانی، عناصر باغ

-

صفحات 14-21در شهرهای سنتی ایران، ریتم قرارگیری دانه های شهری بسته به شیوه تامین آب شهرها شکل گرفته است. در این میان باغات ایرانی نقشی کلیدی در شکل گیری پیکره شهر و منظر شهرهای سنتی داشته و عامل پیوستگی دانه های معماری، زیرساخت های سبز و اندام های طبیعی شهر به شمار می رود. سه عامل آب، گیاه و دانه های معماری ساختار و پیکره شهرهای سنتی ایران را شکل داده است. پژوهش حاضر «شارباغ» ایرانی یا همان باغ شهر ایرانی را مورد مطالعه قرار می دهد و به دنبال کشف رابطه میان این سه عامل در شکل گیری منظر پایدار شهرهای سنتی و جایگاه باغ ایرانی به عنوان عنصر کلیدی در شکل گیری باغ شهرهای ایران می باشد. حاصل تعامل این سه عامل، شکل گیری ساختار شهر و ایجاد کمربندی سبز اطراف شهرها به واسطه باغات و مزارع و تبدیل دانه های معماری به دانه های سبز به واسطه حیاط باغ ها و خانه باغ های شهری است. نتیجه این اندیشه ایجاد یک میکروکلیمای مناسب در مایکروکلیما و بستری نامناسب است. از طرفی این عناصر در ترکیب و تعاملی پایدار منظری پایدار را ایجاد کرده اند که در آن نه تنها بهره وری کامل از طبیعت به واسطه انسان انجام شده بلکه حیاتی جاودان به شهرهای سنتی بخشیده است. روش تحقیق در این پژوهش به گونه اکتشافی، مبتنی بر مشاهدات میدانی و عکس های هوایی و ماهواره ای می باشد. نتایج حاکی از آن است که منظر شهرهای سنتی ایران در ترکیبی کاربردی از آب، گیاه و دانه های معماری شکل گرفته که علاوه بر ایجاد محیطی مطلوب در شهر و در خانه ها ریتم مناسب و منحصر به فردی را به هر شهر داده که در عین زیبایی، کاربردی نیز است.کلیدواژگان: شارباغ، شهر سنتی، باغ ایرانی، منظر شهری

-

صفحات 22-31معماری ترحیمی در هند دوران پیش از مغول، نمونه های بی شماری از فرم ها و فضاها ازجمله باغ ها را شامل می شود. مفاهیم شکل دهنده به این خاک سپاری ها به صورت قابل توجهی در ارتباط با عادت و رسوم زیارت یا همان بر سر مزار رفتن است. ازجمله آنچه در مقابر افراد بزرگ و مقدس مانند مقابر بزرگان چشتیه (chishti) و همچنین پادشاهان باستان می بینیم. در هند از اوایل سده 13 تا میانه سده 16، سیر تحول منظر و معماری در مسیری متضاد با یکدیگر، هم در مقیاس و هم در فضاها پیشرفت. مناظر ترحیمی (فرم، مکان و نحوه قرارگیری و...) رابطه نزدیکی با رسم و آئین های خاک سپاری و درواقع مردم شناسی دارد. مرگ، خاک سپاری و مجلس یادبود هویت را نشان می دهد؛ انتخاب سایت خاک سپاری، سبک و موقعیت مقابر، همراه با شیوه ای که مراسم ترحیم سازمان دهی شده و گرامی داشته می شده است، به بازسازی روابط دودمانی و زنده نگه داشتن خاطره شان کمک می کند. هدف این مقاله تاکید بر چند نکته در ارتباط به انسان شناسی و معماری منظر ترحیمی (باغ مقبره) در قلمرو سلاطین دهلی است.

این مقاله با اشاراتی به رابطه مردم شناختی و معماری منظر ترحیمی در دوره سلاطین دهلی و برشمردن نمونه هایی از مناظر آرامگاهی شبه قاره هند از 1206 م تا 1555 م، سیر تحول فضاهای آرامگاهی از تک بناهای کوچک تا مجموعه های آرامگاهی با محورهای تعریف شده در بافت شهری و باغ های چهارقسمتی (چهارباغ) را نشان می دهد.

نتایج این پژوهش نشان می دهد که آثار تقسیمات چهارتایی معروف به چهارباغ در منظرهای ترحیمی (باغ مقبره ها) در هند دوران پیش از مغول وجود داشته است و شکل گیری مجموعه های آرامگاهی با بناهای مقابر در میانشان در اواخر این دوره ارتباط مستقیم با تغییر مراسم و مقیاس آن دارد.کلیدواژگان: منظر ترحیمی، معماری ترحیمی، دوران پادشاهی دهلی، چهارباغ -

صفحات 32-39کوشک مهمترین عنصر معمارانه در باغ های ایرانی و نشان دهنده نهایت ذوق و هنر ایرانی در ترکیب باغ و بناست. معمولا این بناها را در فضای میانی باغ و در محل تلاقی دو محور طولی و عرضی به گونه ای می ساختند که از چهار طرف دیده شده و تاثیر ترکیب هندسی چهارباغ ایرانی را دوچندان کند. اگرچه به لحاظ شکل گیری و دسته بندی ساختاری، گونه های نسبتا متفاوتی از این فضاهای معمارانه در ترکیب باغ های ایران دیده می شود. با این وجود گونه بناها با تقسیمات نه قسمتی در کوشک باغ های ایرانی استفاده ای پر دامنه ای دارند. این گونه معماری حاصل آمیزش سه خواست اساسی معماری، یعنی توجه به زیبایی، عملکرد و ایستایی است به نحوی که با ترکیب مناسب احجام، به زیبایی هر چه بیشتر آنها افزوده می گردد، وجود سلسله مراتب برای نیل به قدرت بخشی به عملکرد کاخ و همچنین مهار بار های رانشی حجم میانی کمک شایانی به پایداری این فضای ایرانی نموده است.

اینکه چرا این گونه از معماری خاص 9 قسمتی در باغ های ایرانی از اقبال فراوان در طول تاریخ از دوره هخامنشی تا قاجار برخوردار شدند؟ سوالی است که این نوشتار به دنبال پاسخ گویی به آن است. سوال دیگر این است که در شرایط یکسان و در قلب چهارباغ ایرانی چرا این نقشه بعضا به صورت کاملا بسته (چهارصفه) و در پاره ای از مواقع ترکیبی از فضاهای بسته و نیمه باز به صورت نقشه هشت بهشت و در مواردی اندک همانند عمارت مرکزی قصر قاجار در تهران به شکل کاملا نیمه باز (آلاچیقی) اجرا شده است؟

می توان اینگونه نتیجه گرفت که وجود چهار نمای همگن که به محور های چهارباغ باز می شود، به قدرت بخشی توده معماری بر توده منظر و همچنین یکی شدن و ادغام فضایی آن ها کمک شایانی نموده است و اصولا معماری سلسله مراتبی در قلب ساختار چهارباغ، جوابی مناسب تر از فضای نه قسمتی نخواهد یافت. همچنین نحوه استفاده اقلیمی-فصلی از یک سو و توجه به عملکرد زیستی-تشریفاتی و بعضا مراسمی، جهت جوابگویی به خواسته های حکومت ها را می توان از دلایل عمده تفاوت ساختاری این کوشک ها در قلب چهار باغ ایرانی برشمرد.کلیدواژگان: باغ ایرانی، کوشک، چهارصفه، هشت بهشت، ابنیه نه قسمتی -

صفحات 40-47در میان کاخ های شاه عباس اول در مازندران، عمارت عباس آباد به جهت ویژگی های بارزی که دارد، قابل توجه است. این عمارت را می توان محل تلاقی باغسازی غیررسمی و باغسازی رسمی دانست؛ چنانکه در آن یک دریاچه مصنوعی که عناصر باغسازی آزادانه اطرافش شکل گرفته اند و فضایی کاملا هندسی که با ارتفاع از سطح دریاچه قرارگرفته، به هم متصل می شوند. همزیستی این دو بخش و ارتباط نزدیک این اقامتگاه با طبیعت جنگلی اطراف، نمایانگر نوعی ارتباط اصیل میان برخی از باغ های صفوی با منظر طبیعی است؛ رابطه ای که به صورت تمایل برای «حفظ» یا «بازتولید» طبیعت با ویژگی های بکر و رام نشده آن بروز می کند. ازاین روی در عباس آباد بهشهر به جای یک کاخ سلطنتی باشکوه، اقامتگاه شکاری ساده ای ساخته می شود که گوشه عیش شاه عباس اول است.کلیدواژگان: باغ عباس آباد، باغ صفوی، باغ ایرانی، باغ رسمی، باغ غیررسمی

-

صفحات 48-55علی رغم مطالعات بسیار در مورد باغ ایرانی و وجوه مختلف آن خصوصا در دهه های اخیر، ابعاد ناشناخته و مورد اختلاف در باب دلایل شکل گیری و هندسه باغ بسیار زیاد است. در این بین الگوی چهارباغ، که باغ را حاصل دو محور متعامد با وجود کوشکی در محل تقاطع می داند، با استناد به برخی شواهد چون نقوش برجسته چلیپایی و توصیف از بهشتی که آدم ابوالبشر از آن رانده شده است، به عنوان کهن الگوی باغ ایرانی معرفی شده است. در سال های اخیر این تفکر توسط برخی از محققین مورد نقد قرار گرفته است.

در واقع، وجود الگوهای مختلف برای یک پدیده مانند باغ ایرانی نشان از ناتوانی پاسخگویی یک الگوی شکلی ثابت برای آن پدیده است، لذا شایسته است تلاش ها در جهت کشف الگوی پنهانی باشد که بتواند انواع گونه های شکلی را تولید نماید. مقاله با سوال از چگونگی شکل گیری رابطه انسان، آب و درخت در باغ ایرانی به دنبال یافتن کهن الگویی برای باغ ایرانی است که توجیه کننده انواع فرم های توسعه یافته باغ ایرانی نیز باشد. هدف غایی این نوشتار به دنبال معرفی الگوی پنهان باغ ایرانی از ورای بررسی رابطه انسان، آب و درخت در نمونه ها و فرم های متنوع باغ ایرانی است.

نتایج تفحص در عناصر باغ ایرانی، نحوه استفاده از فضاهای آن و زیبایی شناسی خاص ایرانی، حاکی از وجود و تکرار الگوی سه گانه آب، گیاه و نظرگاه در باغ ایرانی است که تلاش در همه گونه های کالبدی بهره مندی از منظر آب و گیاه، به عنوان مهمترین عناصر طبیعی، از روی مکانی به عنوان نظرگاه است.کلیدواژگان: باغ ایرانی، کهن الگو، آب، گیاه، نظرگاه -

صفحات 56-65این مقاله به بررسی برخی از باغ های هندی-ایرانی قرن شانزدهم و هفدهم در منطقه «دکن»، در جنوب هند می پردازد. مدعای مقاله این است که نوع زمین و شیوه مدیریت آب در جنوب هند گونه ای از منظر را پدید آورده که به طور قابل ملاحظه ای با آنچه در شمال هند و ایران وجود دارد متفاوت است. باغ های دکن که در نزدیکی منابع فراوان آب قرار گرفته اند، پاسخی به بستر جغرافیایی و فرهنگ بومی هستند. عمارت هایی که در میان آب ساخته شده اند و جزئیات استخرهایی که در دوران پادشاهی عادل شاهیان در نزدیکی «بیجاپور» ساخته شده اند شاهد این امر هستند. جانمایی کاخ ها بر روی تپه های مشرف بر آب و باغات وسیع نیز پاسخی به بستر جغرافیا و فرهنگ بوده؛ چنانکه در حیدرآباد و «گلکندا» در دوران سلسله قطب شاهیان شاهد آن هستیم. در این منطقه و همچنین در بیجاپور، از باغها در فصول بارانی نیز استفاده می شده است. با اینکه زنان، شاه را در بازدید از باغات همراهی می کردند، باغ های ویژه زنان، با نام باغ های «زنانه»، تنها در ارگ وجود داشته است؛ جایی که بتوان حفظ حریم خصوصی آنان را تضمین کرد. مردم، به طور کلی، تنها گاه به گاه و پس از بازدید سلطان بود که می توانستند از باغ های لذت شاهی بهره مند شوند. باغ های دکن همچون دیگر باغات شبه قاره هند نه فقط در روز که خصوصا شبها مورد استفاده بوده است. از آنجا که بسیاری از گل های هندی سفید، بسیار خوشبو و جاذب حشرات شبانه اند و شبها برای گرده افشانی باز می شوند، یک سنت شب نشینی هندی به نام «ماه- باغ» وجود داشته است. به طور سنتی دیرزمانی است که در شبه قاره هند گل های خوشبو با عشق و انگیختگی مرتبط است و عاشق پیشگان در باغ ، خصوصا در خنکای روز که گل ها عطر خود را می پراکنند محظوظ می شدند. در نتیجه می توان گفت هرچند باغ های دکن از خانواده باغ های هندی-ایرانی بوده و به نوع مشابهی استفاده می شده است، نوع زمین و استفاده از شیوه های هندی در مدیریت و ذخیره آب در منطقه دکن، منظری را رقم زده است که ریشه در خاک هند دارد. اگر این باغ ها به لحاظ سبک، ایرانی هستند اما مزاج و طبعی بسیار هندی دارند.کلیدواژگان: منظر ایرانی، منظر هندی، باغ های هند، منطقه دکن

-

صفحات 66-73پراکندگی آثار برجای مانده در دشت پاسارگاد، شناسایی و درک این مجموعه را به عنوان اولین پایتخت هخامنشیان دشوار می کند. یافته های باستان شناسی عمدتا بر اجزا و بناها متمرکز بوده و ساختاری کلی ارائه نمی کند.

تحقیق حاضر در ابتدا با بررسی اسناد تاریخی در کنار یافته های اخیر باستان شناسی سعی در اثبات وجود باغ به عنوان عامل پیونددهنده در محوطه پاسارگاد دارد. در گام دوم با تحلیل عناصر به جامانده مبتنی بر برخی سنت های منظره پردازی ایرانی همچون وجود محور اصلی و تقارن درصدد یافتن هندسه باغ و الگوی حاکم بر آن برآمده است.

نتایج حاکی از آن است که کلیه بناهای دشت پاسارگاد در یک ساختار منظم فضایی احداث شده اند و باغی وسیع بر کلیه عناصر احاطه داشته است. «باغ شاهی» تنها بخش کوچکی از این مجموعه وسیع بوده و درواقع به نظر می رسد که نخستین مرکز حکومتی-آیینی هخامنشیان یک باغشهر با ساختاری منظم و یکپارچه بوده است.کلیدواژگان: پاسارگاد، باغ شاهی، باغشهر، باغ ایرانی، دوره هخامنشی -

صفحات 74-81این نوشتار با بررسی عناصر مختلف حیاط شیرها در الحمراء در آندلس، به نحوه ادراک این فضا از طریق آن ها می پردازد. تمرکز اصلی مقاله بر آثار قرن چهاردهم میلادی است. جزئیات معماری، ازجمله تزئینات مقرنس کاری، سنگ نوشته روی آب نمای مرکزی و کتیبه های شاعرانه در تزئینات سطوح نما، در ارتباط با کارکرد، معنا و نقششان در ادراک فضا بررسی شده اند. همچنین نحوه قرارگیری حیاط شیرها و ارتباط آن با کل باغ در بستر تاریخی اش، ارتباط حیاط با فضاهای مجاور آن و چارچوب کلی حیاط ازنظر ارتباط فضاهای درونی و بیرونی موردتوجه قرارگرفته است. اثرات ادراکی تمامی این ویژگی های معمارانه و شاعرانه، به علاوه تاثیر آب ساکن و جاری در فضای حیاط، تنها یک اثر صرف زیباشناسانه ایجاد نمی کند؛ بلکه تمامی این ها مشخصا برای آزادسازی و هدایت قوه تخیل ما طراحی شده اند.کلیدواژگان: حیاط شیرها، باغ الحمراء، ادراک، تخیل، باغ

-

صفحات 82-89«باغ- محور» - محورهای ساختاری شهری تاثیرپذیرفته از باغ- یک عنصر شهری شاخص در شهرهای دوران صفویه است. نوسازی و توسعه شهر، با کمک باغ- محورها در شهرهایی همچون قزوین، اصفهان، مشهد، نیشابور و شیراز در دوران صفویه صورت گرفت. حاکمان نخستین صفوی، پایتخت های جدیدشان را با اتصال باغ شهرهایی به شهرهای موجود برپا می کردند که حول نوع خاصی از فضاهای باغ عمومی (میدان و خیابان) سازماندهی شده بود.شیراز، حیات شهری خود را وامدار حضور باغ ها، چه به صورت باغ-محور و چه به صورت باغ های حکومتی بوده است. پرسش اصلی در این مقاله این است که نقش باغ- محورها در رشد و توسعه شهر شیراز چیست؟برای پاسخ به این سوال ابتدا نگاهی اجمالی به چیستی مفهوم باغ- محور و شرحی بر دو باغ-محور شمالی و غربی شهر شیراز صورت گرفته و سپس نقش آن ها در توسعه شهری در دوران زندیه و بعد از آن بررسی و تحلیل شده است. نتایج نشان می دهد که باغ-محور، دستاوردی بوده است در شهر تاریخی شیراز که در دوران صفویه برای تبلور کالبدی ساختار شهر در نظام جدید فضایی ابداع شده بود. باغ-محورهای شمالی و غربی شهر، علاوه بر آن که عنصر هویت ساز در نظام شهری بوده اند، نقش مهمی نیز در توسعه های شهری داشته اند. شکل گیری این دو باغ محور، از یک سو نمایش دهنده اصول باغ سازی صفویان برای هویت بخشی به ورودی های شهر (دروازه اصطخر و دروازه باغ شاه) بود و از سوی دیگر به توسعه شهر در دوران زندیه، قاجار و پهلوی جهت می بخشید. در دوره کریم خان زند نیز ایجاد مجموعه شاهی و تلفیق آن با باغ های حکومتی ازجمله «باغ نظر» و باغ منضم به «ارگ کریم خان»، در کنار تقویت دو باغ-محور شمالی و غربی، این نظام شهری را تقویت کرد. در اولین مراحل توسعه شهری شیراز، باغ-محور غربی شهر در دوره پهلوی اول به خیابان کریم خان زند تبدیل شد. در دوره های بعد، تجمیع فعالیت های مهم اداری در این خیابان و فرآیند توسعه در طی سال ها، منجر به تفکیک و نابودی این باغ ها شد.کلیدواژگان: باغ، محور، شیراز، باغ ایرانی، صفویه، زندیه

-

صفحات 90-95بازنمایی ساختاری و فضایی گونه های متنوع باغ ایرانی در دوره های مختلف با تکیه بر مستندات و مکتوبات تاریخی و باستان شناسی از شاخه های مهم پژوهش در حوزه باغ ایرانی است. پژوهش هایی که به فهم ما از باغ ایرانی، الگوها و ساختارهای آن در دوره های مختلف کمک می کند.

این مقاله مشخصا به معرفی الگویی کمتر شناخته شده از باغ ایرانی در دوره های پیشین با تکیه بر روایتی از مثنوی هفت پیکر نظامی گنجوی می پردازد. در این مثنوی، نظامی تصویر باغی مرکب را بازنمایی کرده است؛ باغی که از دو بخش بیرونی ( گلستان) و درونی (بوستان)تشکیلشده و میان این دو غرفه ای(حجابگه) قرار دارد. بوستان فضایی محصور در میان دیوارهای بلند و در قرق زنان است و نظر افکندن به آن تنها از این غرفه ممکن است. این تصویر، گونه ای از باغاست که در مثنوی ویس و رامین نیز نشانه هایی از آن یافت می شود. این تصویرها ممکن است برآمده از شکل فضا در روایت اصلی داستان هایی باشند که ریشه قدیمی تری دارند؛ و یا ممکن است شاعری چون فخرالدین اسعد گرگانی و نظامی در بازتعریف و روایتگری داستانی قدیمی تر، به تجربیات بصری خود در سده های پنجم و ششم مجال داده باشند تا به میزانسن برخی صحنه های داستان های آن ها تبدیل شوند. پاسخ دادن به این پرسش دشوار است؛ اما همین تصویر قابل فهم از باغ که در آثار هر دو این شاعران بازنمایی شده است، نیز ما را با شکل و الگویی جدید از باغ آشنا می کند و به فهم ما از باغسازی ایرانی می افزاید. -

صفحات 96-103محمد شهیر (1948-2015 م.)، معمار منظر هندی، مرمت و بازسازی باغ های تاریخی مختلف در هند و افغانستان را بر عهده داشته است. این مقاله به رویکردها و روش های وی در سه پروژه بازسازی منظر می پردازد : باغ مقبره همایون و محور مرکزی ساندر نرسری* در دهلی، و باغ بابر در کابل. شهیر درک عمیقی از باغ ایرانی داشت و اندیشه نهفته در باغسازی گورکانی را به خوبی می شناخت. حفظ اصالت باغ های تاریخی نتیجه این شناخت و همچنین دقت و توجه شهیر به جزئیات است. درک روح هندسه باغ به همان صورتی که وجود داشت و پیروی از آن، اساس کار وی را تشکیل می دهد. در این پروژه ها، بازسازی جریان آب و احیای طرح کاشت بر اساس شواهد تاریخی و همچنین بهره گیری از شیوه های محلی، با هدف بازگرداندن باغ به دوران شکوفایی خود انجام شده است.

درک شهیر از زمینه های فرهنگی محلی و طراحی منظر مطابق آن، و سبک خاص او که در عین سادگی، مداخله حداقل و پایبندی به اصالت طرح، قادر بود کارکردهای مدرن را نیز به صورت یکپارچه در باغ های تاریخی تعبیه کند، این سایت ها را به جاذبه های مهم گردشگری تبدیل کرده است.

-

Pages 6-13Gardening Art is an outcome of Iranian civilization and culture which its elements and principles has not been revealed completely yet. Besides the main street and streamlets, Persian garden is composed of some other elements which their entity and role in creating the garden should be recognized. Surrounding wall, which has been repeated in all samples of authentic Persian garden is a kind of mixture of iconic cultural complexity and functional simplicity elements. Surveying the wall as a conspicuous element can reveal some secrets in Persian gardening style and its role in landscaping.

Wall is a multi-conceptual element which its application to enclose the garden, regardless of its functional benefits, has an important role in creating an Iranian identity for the garden, as Persian Garden is an arena for illustrating the nature and humans pondering in verses of cosmos. Due to the audience mentality and the landscape (and space) capacity, this field needs to adhere to certain traditions which this wall is among the most important ones.Keywords: Wall, Persian Garden, Garden's elements -

Pages 14-21The arrangement rhythm of urban grains in traditional cities of Iran are formed in accordance with the water supply system of the cities and villages. In this regard, Persian gardens play a key role in formation of city structure and urban landscape of traditional cities as well as incorporation of architectural grains , green infrastructure and green natural organs of the city. The triple factors of water, vegetation and architectural grains can be identified as the main factors in formation of Iranian traditional city structure. The current research studies Persian Shârbâgh or Persian city garden in order to discover the relation between these triple factors in formation of sustainable landscape in traditional cities and the role of Persian garden as a key factor in formation of Persian city gardens. The interaction of these triple factors results into formation of city structure and creation of a green belt in peripheral parts of the city. This is enabled by the presence of gardens and fields as well as the existence of architectural grains that can be considered as green grains since they are all considered courtyard houses and garden houses. Not only does this arrangement provide a desirable micro climate in an undesired context, but also it creates a sustainable landscape within a sustainable composition and allows an interaction which enables a full productivity of nature by human and offers a perpetual life of the traditional cities. Here, an exploratory method based on field observations and aerial and satellite photographs are used. The results indicate that the urban landscapes of past Iranian cities were formed in a combination of water, vegetarian and architectural grains which provided an apt microclimate in houses and cities and resulted in a unique, appropriate, functional and aesthetic rhythm in cities.Keywords: Sharbagh, Traditional city, Persian Garden, Urban Landscape

-

Pages 22-31Funerary architecture in Pre-Mughal India offers numerous examples of forms and settings, including gardens. The concepts of these burials are probably connected with the habit of ziyarat or visiting the tombs, i.e. those of saint patrons such as the Chishtis, but also of ancient kings. From early 13th to mid 16th century, the evolution of landscape and architecture followed a contrasted line, both in scale and setting. The goal of this paper is to highlight a few hints on the anthropology and architecture of funerary landscape in the Delhi sultanate.Keywords: Garden, Funerary architecture, Delhi, Sultanate Period, Chahar bagh

-

Pages 32-39The Pavilion can be outlined among the most important architectural identity elements in Persian gardens. Usually these structures were built in the middle of the garden and at the confluence of two longitudinal and transverse axes in such a way that it could be seen from four sides to maximize the geometrical composition of the Persian four-garden. Although relatively different reasons for the formation and structural categorization of these architectural spaces can be seen in Persian gardens. Nine-part divisions in Iranian pavilion are of an extensive use. This type of architecture is the result of the fusion of three basic requests in architecture: Attention to beauty, function and stability. Thus, the right mix of volumes, adds to their beauty. The existence of hierarchy to achieve empowerment for the palaces performance and also the inhibition of central thrust loads, have made significant contributions to the sustainability of these Persian environments. On the other hand, this plan has strengthened the permanent request of centralization in four-part buildings, adorned Persian gardens from the Achaemenids period so far in two major forms of introvert and extravert. In this article firstly the need for such spaces in the existence of hierarchies and response to promotional aspects of palaces is demanded. Another question is that, in the same condition and in the heart of the Persian garden, why is this map implemented sometimes completely closed (Châhâr-Sofe), at times a combination of closed and semi-open spaces (Hasht-Behesht) and in rare cases like the central building of Qajar palace in Tehran, completely semi-open (Canopies)? The results of this study show that the existence of four homogeneous facades that open to the axis of the charbâgh, empowered the architectural mass over the mass of landscape and helped their coalescence and spatial fusion and in general, the hierarchical architecture in the heart of a four-garden structure would not have a better answer than a nine part space. Also it seems that, on one hand, a climatic-seasonal usage and on the other, paying attention to the bio-ritual and occasionally ceremonial functions, in order to meet the demands of the governments, are among the main reasons for these changes.Keywords: Apadana, Chahar, Sofe, Hasht-Behesht, Nine-part buildings, Pavilion, Persian Garden

-

Pages 40-47Among Shâh Abbâs Is palaces in Mâzanderân, the Abbâsâbâd estate is outstanding by its original features: it linked an informal garden, the elements of which are loosely assembled around an artificial lake to a formal space, on higher grounds, with a geometrical outlay, more common in the art of Persian gardens. The coexistence of these juxtaposed parts and the close relation of the residence with the surrounding forest, the lack of outside walls customary in Persian gardens, hint at an original relation of some Safavid gardens with the natural landscape i.e. a will to reproduce or preserve nature in its wilder aspects, with the intent, not of building a great Royal garden, but rather, a simple hunting residence: a gusheh-ye eysh-e shâh, a "pleasure corner for the king".Keywords: Abbasabad garden, Safavid gardens, Persian Garden, Formal garden, Informal garden

-

Pages 48-55Despite the comprehensive study especially during recent years in regard with phenomenon of Persian garden, the unknown dimensions and discrepant issues are so much; regarding formation and geometry of Persian garden. In between, the Châhârbâghs pattern which knows it; garden is consequences of two orthogonal axes with existence a palace in confluence location of axes, introduced as archetype of Persian garden by citing some of evidence; like designs of cruciform inscription and descriptions of paradise where Adam driven from there; This idea had criticized by some researchers in recent years. Current article criticizes common archetype of Châhârbâgh as viewer is on the vision point where perception by user is impossible and more importantly; its not able to justify all Persian garden forms. By question about how formation the human, water and trees relations in Persian garden and also be able to justify various of developed forms in Persian garden; hence this article is going to introduces the existence hidden pattern in Persian garden that be able to justify all developed forms of Persian garden.

Researching about Persian garden elements and how space usage and Iranians specific aesthetic are indications concerning existence of triplet pattern water, plants and Nazargâh (Belvedere) in Persian garden; that effort in all of physical species was toward utilizing water and plant perspectives from the location like Nazargâh as most important of natural elements.Keywords: Persian gardens, archetype, Chaharbagh, Water, Plant, Nazargah (Belvedere) -

Pages 56-65The paper examines some sixteenth and seventeenth-century Indo-Iranian garden sites of the Deccan in southern India. It argues that terrain and water management practice in southern India resulted in a landscape expression that differed markedly from that in northern India and Iran. The gardens of the Deccan, located near large water storage tanks, were responses to the geographical context and to native cultural practice. This is strongly suggested in the evidence of water pavilions and the detailing of water edges at, or near, Bijapur, in the sultanate of the Adil Shahs. The placement of palaces on hills overlooking expanses of water and gardens, as at Hyderabad and Golconda, in the sultanate of the Qutb Shahs, was also a contextual response. Gardens were enjoyed during the season of the rains, at Bijapur as well as at Golconda/Hyderabad. Although ladies accompanied the sultans during their visits to gardens, gardens specifically for ladies, called zenana gardens, were located only in the citadels where the privacy of ladies could be ensured. The public, in general, could enjoy royal pleasure gardens only occasionally, following a royal visit. Gardens in the Deccan, in common with those elsewhere in the Indian subcontinent, were used not only by day but especially in the evening. Because many Indian flowers open for pollination in the evening and are white, strongly scented, and tubular to attract nocturnal insects, an Indic tradition of an evening, or moon garden, existed. Traditionally, in the Indian subcontinent, scented flowers have long been associated with love and arousal and it would seem that amorous pursuits were enjoyed in gardens, in particular, at the cooler time of the day when flowers released their fragrances. In conclusion, it could be said that although the gardens of the Deccan share a family likeness with other Indo-Iranian gardens and were used in similar ways, the terrain of the Deccan and the reliance in this region on native Indic practices of water storage and management resulted in landscapes that were rooted in the Indian soil; if, stylistically, these gardens could be considered Iranian, temperamentally they were very much Indian.Keywords: Indo Iranian gardens, Indian gardens, Iranian gardens, Deccan

-

Pages 66-73The recognition and perception of the whole Pasargade complex as the first capital of Achaemenes is not that simple, due to the dispersion of the ruins in the whole plain. Archeological findings were mainly concentrated on components and buildings without providing a general structure for Pasargade. This research, firstly, attempts to prove the existence of a garden as a connecting factor in Pasargade area by studying historical documents along recent archeological findings. Secondly, by analyzing the remained components, based on Persian landscaping traditions such as the existence of the main axis and symmetry, tends to find the geometry of the garden and its pattern. The results indicate that all of the buildings in Pasargade plain are constructed based on a spatial structure and that a large garden surrounded all the elements. The royal garden was only a small component of this large compound. In fact, it seems that the first governmental-ritual Achaemenid center was being constructed under the form of a garden-city with an ordered and integrated structure.Keywords: Persian gardens, Pasargadae, Garden- city, Achaemenid era

-

Pages 74-81This paper explores perception by examining various elements of The Court of the Lions at The Alhambra in Andalusia, focusing mainly on the fourteenth century. The position of The Court of the Lions in relation to the site of The Alhambra is set out within its historical context. The paper outlines the relationship of The Court of the Lions to its adjacent spaces: The Hall of the Two Sisters, The Hall of the Abencerrajes and The Lindaraja Mirador. The muqarnas prisms in the domes of the two halls are described and explored, particularly in terms of how they might function perceptually. The overall context of The Court of the Lions is briefly described in terms of outside and inside spaces. Architectural inscriptions are described and interpreted, particularly poetic epigraphs on specific locations. The perceptual effects produced by all these architectural and poetic features, as well as by still and moving water in the courtyard, do not have a merely aesthetic effect; they are also designed specifically to release and guide our imagination.Keywords: Court of the Lions, Alhambra, Perception, Inscription, Garden

-

Pages 82-89"Garden-axis" the urban structural axis influenced by the gardens- is a great urban element in the cities of the Safavid era. Cities such as Qazvin, Isfahan, Mashhad, Shiraz and Nishabur, developed with garden-axes during this era. The first Safavid rulers built their new capitals by connecting them to old towns with garden cities which were organized around a special kind of public garden spaces (squares and streets).

Shiraz, owes its civic life to existence of gardens, such as "Garden-axes" and also governmental gardens. The main question in this article is What is the role of garden-axes in the development of Shiraz?

To answer this question, at first the concept of garden-axes and two garden-axes on north and west of the city is explained. Then their role in urban development during the Zand era and after it was analyzed and evaluated.

The results show that garden-axes has been an achievement which drove gardens in the historic city of Shiraz in the Safavid era for the physical manifestation of the spatial structure of the city in the new system. Not even northern and western garden-axes of the city were the identification elements in the urban system, but they also have an important role in urban development.

The formation of these garden-axes, represent Safavid basics of building gardens for identifying of the entrances to the city (Estakhri gate) and also led the development of the city during the Zand and Qajar and Pahlavi era. In the period of Karim Khan Zand Government, creation and integration of gardens with government buildings, including Bagh-nazar and Arg-Karimkhan Garden, along with revival of two garden-axes of north and west, strengthened the urban system.

In the early stages of urban development of Shiraz in the first Pahlavi era, the western-oriented garden-axes became Karim Khan Zand street and in later periods, the integration of important administrative activities in this street and the process of development, led to the breakdown and destruction of gardens.Keywords: Garden-axes, Shiraz, Persian Garden, Safavid, Zand -

Pages 90-95Structural and spatial representation of various gardens of different era in Iran based on archeological and historical literatures and documents is one of the major fields in surveying Iranian gardens. These surveys can assist us to gain a better perspective and understanding of pattern and structure of Iranian gardens.

Utilizing a story from Masnavi Haft-Paykar, this current article attempts to introduce a lesser known pattern of Iranian gardens belonging to past historical periods. In this poetry, Nezami describes a complex garden composed of two parts, an internal (Golestan) and an external (Boostan) parts. A mansion (Hejabgah) existed in between those parts. Boostan was an enclosed part located between high walls exclusively for womens privacy and occupancy. The view of Boostan was only available through the mansion. This represents a kind of garden which can be found in Masnawi of Vis-O-Ramin to some extent. Similarly, these spatial images may be extracted from earlier stories with much older historic roots in literature. Furthermore, it is possible that poets such as Fakhreldyn Asad Gorgani and Nezami in narrating older stories visualized their knowledge of fifth and sixth centuries so that the stories could be matched with the ancient stories. Finding a proper answer to this question is extremely difficult. However, existing images in works of both poets can help us in recognizing a new configuration and pattern and allows us to gain a better comprehension of garden design in Iran.Keywords: Persian Garden, Complex garden, Nezami Ganjavi, Masnawi Haft-Paykar -

Pages 96-103Landscape Architect Mohammad Shaheer (1948-2015) was the principal consultant in the restoration of several historic gardens in India and Afghanistan. This article presents his particular approaches and methods in three landscape restoration projects: Humayuns Tomb gardens and Sunder Nursery central axis in Delhi, and Babur garden in Kabul.Shaheer had a deep understanding of Persian Garden and was the Master, discerning the design intention of the Mughal builders. Restoring the authenticity of these historic gardens is the result of this understanding and also his special attention to details. Restoration of water flow and planting in these projects is carried out based on historic description also considering local tradition with the aim of bringing the garden back to the state of a flourishing orchard.

Shaheers thorough understanding of local cultural context and his special style in design_ simple yet to great effect_ has ensured modern functions are incorporated in the historic gardens and turned them into major tourist attraction sites.Keywords: Mohammad Shaheer, restoration, Humayun's Tomb, Baghe Babur, Sunder Nursery