فهرست مطالب

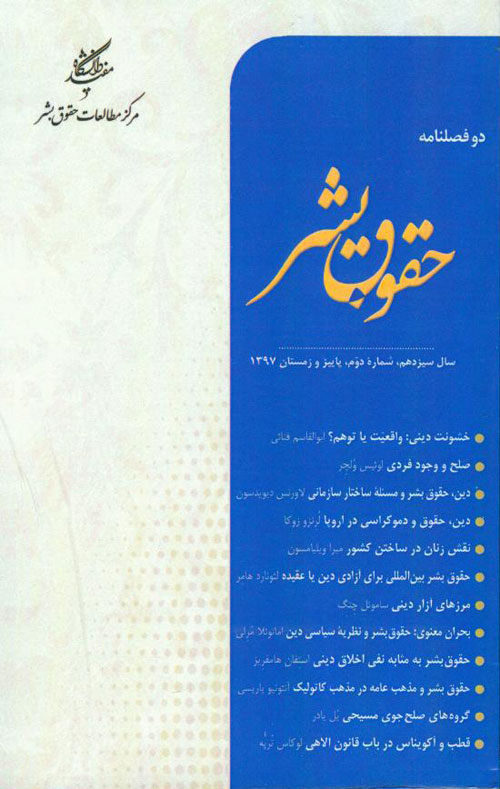

نشریه حقوق بشر

پیاپی 26 (پاییز و زمستان 1397)

- 282 صفحه،

- تاریخ انتشار: 1397/12/01

- تعداد عناوین: 12

-

صفحات 3-30پرسش اصلی این مقاله این است: «آیا خود دین نقشی در خشونت سیاسی بازی می کند؟». در آغاز اصطلاحات مربوط و رایج در ادبیات این بحث، مانند ”دین“؛ ”خشونت دینی“؛ ”خشونت سکولار“؛ ”خشونت سیاسی“ و ”فعل اختیاری“ را تعریف می کنم. سپس به بررسی دو استدلالی خواهم پرداخت که می توان به سود ادعای اینکه خود دین یگانه علت به اصطلاح نوع دینی خشونت سیاسی است، اقامه کرد، و از این بحث نتیجه خواهم گرفت که این دو استدلال در معرض نقد قرار دارند و هیچیک قادر به تایید ادعای مذکور نیستند. در پایان تبیین مورد قبول خود از علت و ریشه اصلی خشونت سیاسی به نحو عام و راه حل درست آن را پیشنهاد خواهم کرد. همچنین از بحث خود نتیجه خواهم گرفت که تفکیک مشهور میان خشونت دینی و خشونت سکولار قابل دفاع نیست.کلیدواژگان: خشونت دینی، خشونت سکولار، خشونت سیاسی، تاریخ دین، تفسیر متون دینی

-

صفحات 31-48تا زمانی که قانون وجود دارد هیچ حقوق بشر جهانشمولی برای صلح وجود نخواهد داشت. این به جهت آن است که خشونت قانونی، چه در عمل و چه در تهدید، از دید کسانی که قانون آن ها را به اجبار سرکوب می کند، با روابط صلح آمیز بسیار متضاد است. قانون نمی تواند بدون آنکه عدالت را نقض کند صلح را فقدان خشونت تعریف کند. همان طور که پاسکال می گوید: «عدالت بدون قدرت بی فایده و قدرت بدون عدالت مستبدانه خواهد بود.» هرچند عواقب قانونی حوادثی مثل سقوط تخته سنگ و چنگ اندازی شیرها همیشه می تواند به دلایل تاریخی نسبت داده شود، اما تجربه به ما می آموزد که بازیگران حقوقی به طور معمول برای قانونی و مشروع نشان دادن اعمالشان، قانون را بر اساس برخی روایت های غیر علی از «حق» و «خوب» پایه گذاری می کنند. بر اساس یک انگاره لیبرالیسم سیاسی که نشانه های آن در اختراع یا (کشف) «من» غیر قابل تقلیل، که فکر می کند آشکار می شود، مشروعیت روایت قانون توسط موضوعات آزاد و عقلانی سیاسی-قانونی اعطا و اخذ می شود. به هر حال در حقیقت، نسبت فلسفی غرب به ما دو ساختار جداگانه برای بحث و بررسی آنچه را که مورد نیاز دو نوع موضوعات عقلانی: پایه ای و علی است، ارائه می دهد. موضوع علی در رابطه با جهان است. عملکرد استراتژیک از آنجایی که منشا اثر است، از جهان مادی و وجود انسان به عنوان غایت خودشان استفاده می کنند. اما موضوع علی به خودی خود ایجاد می شود: خواسته ها و اقدامات آن ها متضمن اثرات تاریخی به وسیع ترین معنای کلمه است. چنین فردی با چنین ساختار و سنتی تبدیل به یک مقصود و یک وسیله در حق خود می شود: به طور مثال یک موضوع برای تحقیق و دانش علمی و به طور کلی وسیله ای برای اهداف موضوعات علی دیگر خواهد بود. از دیدگاه موضوع علی حقوق بشر نمی تواند وجود داشته باشد که مورد استفاده قرار بگیرد یا به عنوان وسیله ای مورد استفاده باشد.

برخلاف موضوع علی تصور می شود که موضوع پایه ای یک منبع واقعی باشد، نه صرفا یک پیوند در زنجیره بی نهایت علل و اثرات. در اصطلاح یونانی این موضوع یک آرخه در مقابل آیتیا است. همچنین این منطبق با معنای اصلی لاتین کلمه sub-ject است. موضوع دوم توسط بسیاری از مفاهیم مختلف از جمله نفس (افلاطون)، آزادی (کانت) و روح (هگل) تعریف شده است. در هر صورت، ایده موضوع پایه ای کار اصلی خود را در حوزه اخلاقی انجام می دهد: این مفهوم قرار است یک پایه امنی ایجاد کند و توضیح دهد که چگونه موضوع علی به عنوان یک ظهور مظاعف ممکن است و همچنین به رد نظریه پولوتوس مبنی بر اینکه انسان گرگ انسان است، بپردازد. اگر موضوع علی بر اساس شیوه حیوانی واکنش نشان می دهد، پس موضوع پایه ای به شیوه منطقی حیوانات پاسخ می دهد. اگر موضوع علی عامل ایجاد اثرات باشد، پس موضوع پایه ای ایجاد کننده است و مسئولیت آن اثرات را به عهده می گیرد.با توجه به تمایزات ذکر شده به نظر می رسد مهم ترین مسئله حقوقی و اخلاقی بشر که در قرن بیست و یکم قرار دارد این است که: چگونه قانون و سیاست می توانند به یکباره، موثر و صرف، قهرآمیز و دلسوزانه، پاسخگو و مسئولیت پذیر باشند؟ به طور خلاصه، آیا ممکن است (با استفاده از ادبیات ظریف) کانت، از خود و دیگر انسان ها، به طور هم زمان به عنوان غایت و وسیله استفاده کرد؟ اما در اینجا مانند جاهای دیگر در فلسفه، ظاهر می تواند فریبنده باشد. زیرا این سئوال پیش فرض های زیادی دارد.این مقاله ارتباط قوی بین مفاهیم قبلی موضوعیت و صلح را بررسی می کند. سوال این نیست که «آیا موضوعات منطقی وجود دارد و آیا می توانند چیز جدیدی مانند صلح عادلانه پیدا کنند؟» در عوض، سوال اصلی و حیاتی این مسئله این است که چطور چیزی سست و بی دوام، مانند «ایده» قادر است چیزی را پیدا کند؟ من تلاش خواهم کرد تا تنش های وحشتناک یا تناقضات بین عدالت و اخلاق، آزادی و مسئولیت، عقل و دلسوزی را پیدا کنم و منشا آن را ردیابی کنم: اراده (یا تمایل) به انکار تراژدی. من ادعا می کنم که مفهوم موضوع پایه ای بیانگر یک تلاش نا امیدانه و بدون هدف نسبت به خنثی کردن آگاهی (و فرار از مسئولیت شخصی) از غم و اندوه ذاتی و تراژدی جهان است. عقل و ایمان وجود انسان را با یک بافت نازک از اظهارات پایه ای که شامل نهادها و تصاویر است می پوشاند. در بهترین حالت این نمادها و تصاویر تنها محرک هستند: اقداماتی که هرگز به اندازه کافی فاصله وسیع وجودی جداکننده بین موضوع پایه ای از موضوع علی را گسترش نمی دهند. همچنین غایات ما از منظورهایمان، سخنان ما از اعمال ها، و به طور کلی از رنج های انسان از سکولار بی پایان و سفسطه مذهبی که در تلاش برای توجیه آن ها هستیم. -

صفحات 49-64این مقاله به دنبال ارائه شناختی از شرایط تاریخی است که همگرایی تعالیم مذهبی انتخاب شده و حقوق بشر را امکان پذیر ساخته و این سوال را مطرح می کند که آیا چنین همگرایی می تواند به موفقیتی که در دین دولتی و یا نهادی یافته است، در یک بروکراسی سلسله مراتبی پیدا کند؟ این مقاله به 3 مورد مطالعاتی نگاه می کند که در آن همگرایی حقوق بشر و مذهب و مبارزه ناشی از آن برای تاثیرگذاری بر رفتار دولت وجود دارد: 1- نمونه آزادی الاهیات مسیحی در آمریکای جنوبی در دهه های 1960-1970؛ 2- نمونه جنبش های خاخام برای حقوق بشر در منطقه اسرائیل از زمان تاسیس آن در سال 1988 تا کنون 3-نمونه Cair (شورای روابط آمریکایی- اسلامی) که در حال حاضر در ایالات متحده فعالیت می کند.

در میان تعالیم اکثر جنبش های بزرگ دینی اصول رفتاری وجود دارد که از مفهوم حقوق بشر جهانی حمایت می شود. هرچند این اصول هنگامی که مورد نیاز نهادها باشند یا دولت یا سلسله مراتب مذهبی تشکیل شده باشند، تحت الشعاع قرار می گیرند. نیازهای نهادها و بروکراسی سلسله مراتبی، حقوق بشر جهانشمول و اصول رفتاری مبتنی بر حقوق بشر جهانشمول را نشان نمی دهد. بلکه، این نهادها، نیازهای خاص گروه های مورد علاقه و نخبه را منعکس می کنند. این نخبگان اغلب می توانند از ایدئولوژی (که ممکن است طبعا مذهبی باشند) استفاده کنند تا منافع خاص خود را جایگزین نیازهای عمومی و منافع جامعه کنند. از آنجا که قواعد رفتاری بر اساس تطابق با دیکته سازمان ها و بروکراسی ها محدود می شوند، حقوق بشر جهانشمول باعث می شود گروه های اقلیت و دیگر افراد در حاشیه جامعه به دنبال تفسیر دوباره و گسترش تعاریف انسان و رفتار شایسته باشند. در کشاش این تفسیر دوباره، قواعد رفتاری در راستای حقوق بشر جهانشمول، همگرایی بین آموزه های دینی و حقوق بشر بیشتر امکان پذیر است. اما بار دیگر این اتفاق در قالب یک اتحاد میان کسانی که خارج از ساختار قدرت غالب هستند، اتفاق می افتد. سه مطالعه موردی که در بالا اشاره داده شده است، نشان می دهد که این کشمکش ها از حاشیه به سه حوزه معاصر راه پیدا کرده اند. نتیجه منطقی که می توان برداشت کرد این است که حامیان حقوق بشر جهانشمول به طرز مضحکی محکوم شده اند که هیچ گاه برای رسیدن به ساختار قدرت مورد نیاز برای اعمال اصولشان در سطح جهانی، تلاش نکرده اند. از این رو، این چنین قدرت ساختاری ای وجود ندارد که برای تحقق این اهداف جهانی طراحی شده باشد. بنابراین حتا در آن موارد نادر که قهرمانان حقوق بشر موفق به رسیدن به قدرت می شوند، هیچ وقت مستقل نبودند و یا توسط ماتریس های نهادی بوروکراتیک قدرت، تضعیف شده اند. تمام این ها به نوع خاصی طراحی شده اند تا منافع خاص و غیر جهانی را ترویج و محافظت کنند. بنابراین، از دیدگاه تاریخی، کسانی که حقوق بشر جهانی را ارتقا می دهند، حتا زمانی که حقوق بشر با آموزه های مذهبی متحد هستند و یا از آنها الهام گرفته اند، همیشه به عنوان بیگانه ها با یکدیگر مبارزه می کنند. برای پیشرفت عمیق تر، باید اصول جهانشمول تبدیل به منافع خاص اجباری شوند. -

صفحات 65-84اروپا یک صورت فلکی از دموکراسی های لیبرال با این اعتقاد است که حوزه عمومی باید کاملا سکولار باقی بماند و استدلال های مذهبی از قلمرو عقل عمومی خارج شوند. ما این نگرش را «اعتماد لیبرال» می نامیم. در سال های گذشته، اعتماد لیبرال تحت فشار قابل ملاحظه ای از طریق موارد متعددی از قبیل حجاب، صلیب در کلاس و داستان کاریکاتورهای محمد [ص] قرار گرفته است. به نظر می رسد اعتماد لیبرال نمی تواند استدلال قانع کننده ای برای تصمیم گیری در مورد این مسائل ارائه دهد.

توضیح عمده برای عدم وجود یک موقعیت لیبرال قانع کننده در شخصیت جزمی منعکس شده است که به جای بیان یک توجیه صحیح، فرض می کند که دین، نمادهای دینی و نظریات دینی بهتر است از منظر دید خارج شوند. این وضعیت مصنوعی به جای حل مشکلات تنش های بیشتری ایجاد می کند و اکنون زمان بررسی این ضعف بنیادین در رشته های اندیشه لیبرال است. این مشکل مسائل مختلف فلسفی را به وجود می آورد. اول به یک چالش معرفت شناختی جدی اشاره می کند، با این عنوان که وضعیت اعتقادات مذهبی در شکل گیری سیاست های عمومی چیست؟ دوم یک مشکل سیاسی در رابطه بین نهادهای سیاسی و مذهبی در سیاست های اروپا را مطرح می کند. سوم، این مسئله اخلاقی بنیادین را به پرسش از عموم ارجاع می دهد: چگونه باید زندگی کنیم؟ با این پرسش که چگونه می توانیم بدون درگیر شدن در این دوره جامع، همان طرز حکومت یکسان را به اشتراک بگذاریم. این امربه این صورت است که باورهای مذهبی و دیگر اعتقادات را در کنار سایر انواع باورها، مهم می شمارد. -

صفحات 85-112«من برای مدت طولانی در تبعید بودم و از انعطاف پذیری، هوش، قدرت و توانایی زنان افغان که از افغانستان و اطراف دنیا آمده بودند، شگفت زده شده ام. من قول می دهم که این زنان بدون هیچ مشکلی کشور را بازسازی کنند.» (Bernard et al, 2008: 150) در این مقاله من بررسی نقش زنان در سناریوهای پس از جنگ به خصوص در موارد حفظ صلح و ساختن کشور را مطرح می کنم. می خواهم از یک بیانیه کلی درباره نقش مهم و برابر زنان در جامعه که هم در اسناد بین المللی حقوق بشر، همچون اعلامیه جهانی حقوق بشر و میثاق بین المللی حقوق مدنی و سیاسی به آن اشاره شده است، شروع کنم. همچنین این اصل توسط ادیان بزرگ از جمله اسلام پذیرفته شده است.

تعداد کمی از سیاستگذاران که مسئول ساختن کشور با هدف نهایی ایجاد جوامع عادلانه دموکراتیک و مسالمت آمیز که حقوق بشر زنان را احترام می گذارد، با آن مخالفت می کنند. با این حال بسیاری از آن ها ابراز نگرانی می کنند که دستیابی به این هدف «بسیار زود» ممکن است قایق را بشکند و در برخورد با یک قایق بسیار لرزان ممکن است تبدیل به هرج و مرج شود و شما نمی توانید ریسک کنید.[1] این مقاله به دنبال تعیین نقش زنان در سناریو های پس از جنگ بدون «سرنگونی قایق» است. این سوال مطرح می شود که تا چه زمانی دخالت زنان باید به تعویق بیافتد تا «وضعیت به ثبات برسد». برخی معتقدند که با توجه به مزایای مختلف دخالت زنان، ترجیحا زودتر به جای دیرتر، دخالت آنان نباید به تعویق بیافتد.[2] در این مقاله به طور ویژه در مورد دخالت زنان در افغانستان تاکید می شود. با این حال افغانستان نمونه هایی از خطر و مشکل ترویج مشارکت زنان در ساختن کشور را فراهم می کند. به عنوان مثال در مورخ 29/9/2008 گزارش شد که یک مامور پلیس افغانی، ملالی کاکار، مورد اصابت گلوله قرار گرفته و کشته شده است و طالبان مسئولیت مرگ وی را بر عهده گرفته است.[3] این نخستین نمونه از ترور مستقیم یک زن مامور پلیس پس از 2001 نبود. سوالی که در این حادثه مطرح می شود این است که آیا تاکید بر ترویج مشارکت زنان در نیروی پلیس پیش از موعد است یا خیر؟ آیا این یک نمونه از «شکستن قایق است» بخشی از ساختن کشور است؟ طرح کلی پیشنهادی این مقاله به شرح زیر است: مقدمه و زمینه های اساسی: برابری و نقش زنان در جامعه: اصول کلی قانونی، اصول اجتماعی و مذهبی؛ زنان و کشور سازی: تعاریف، اصول کلی، اسناد بین المللی و آمار؛ افغانستان: فرآیندها و مشکلات؛ زمینه های تاریخی و مسائل مدرن؛ نتیجه گیری توصیه ها به ویژه برای افغانستان و برای زنان در ساختن کشور به معنای کلی تر. -

صفحات 113-139این مقاله با تشخیص مشکلات ذاتی مرتبط با حقوق بشر بین المللی در آزادی دین یا عقیده، رویکرد جایگزینی را به حق پیشنهاد می نماید.

با توجه به اهمیت دانش و نقش آن در ترکیب با قدرت، می توان از حق سخن گفت. اتخاذ مفاهیمی که ام. فوکو (M. Foucault)، پیشنهاد نموده، زمینه ای را برای تفسیری انتقادی از دین یا عقیده به عنوان بخشی از گفتمان جاری اجتماعی فراهم می سازد. نیازی نیست مظاهر یک دین یا عقیده را کشمکشی بین فرد و دولت دانست، بلکه باید آن را در چارچوبی گسترده تر درک نمود. می توان عوامل دیگری در جهت درک یک عقیده، از جمله اظهارات یک فرد معتقد، را بدون لزوم ارزیابی مزایای آن عقیده بررسی نمود. -

صفحات 141-174حق آزادی مذاهب و یا باورها از زمان آغاز دوران مدرن حقوق بین الملل در ابزار های حقوق بشری به خوبی پایه گذاری شده است. هرچند، آزادی درونی عقیده مورد اعتراض قرار نگرفته است، توانایی آشکار کردن این باورها به طور عمومی به محدودیت هایی برای اهداف خاصی نظیر امنیت عمومی و نظم، سلامت، اخلاق، حقوق اساسی و آزادی های دیگر تبدیل شده است. میزانی از این محدودیت ها در اعمال مذهبی تحت قوانین حقوق بشر بین المللی ممکن است قابل پذیرش بوده و همچنان مورد بحث قرار بگیرد. از آنجا که آزار و شکنجه به دلایل مذهبی یکی از پنج زمینه مندرج در کنوانسیون 1951 مربوط به وضعیت پناهندگان است، حقوق بین المللی پناهندگان نقش مهمی در حفاظت از آزادی مذهبی ایفا کرده است. تا چه میزانی از اعمال محدودیت بر اعمال مذهبی مجاز است؟ و چه میزانی از این محدودیت ها به سطح آزار و شکنجه نیازمند حمایت بین المللی می رسد؟ بررسی قوانین پناهندگی دولت هایی که ادعاهای مرتبط به مذهب را مورد قضاوت قرار می دهند، کمک خواهد کرد مرزهای مبهم تعریف آزار و شکنجه در بستر اعمال مذهبی تشخیص داده شود و برخی از عوامل و گرایشات که بر تصمیم گیری پناهندگان تاثیر می گذارد را مشخص می کند.قسمت اول مقاله ، مرور کلی بر حقوق بین الملل پناهندگان را در رابطه با مذهب ارائه می دهد و زمینه وستفالی را که در آن ایجاد شده است را توصیف می کند. دوران مدرن حقوق بین الملل به شدت تحت تاثیر جنگ های مذهبی و اصل کویوس رجیو، ایوس رلیجیو (Cuius Regio, Eius Religio) قرار گرفت - کسی که حکومت او دین اوست – این اصل بر احترام به حاکمیت ملی و عدم دخالت در امور مذهبی دولت به عنوان ضرورت ثبات بین المللی تاکید دارد. قانون بین المللی پناهندگان که در اصل در واکنش به جنگ جهانی دوم و هولوکاست توسعه یافته است، تلاش می کند که احترام به حاکمیت ملی همراه با حمایت از دغدغه های بشر دوستانه را از طریق اعمال این حمایت ها به افراد خارج از کشورشان به تعادل برساند. قسمت دوم مقاله قوانین پناهندگان که در آن محدودیت های مذهبی یک ترس شناخته شده نسبت به آزادی و اذیت را شامل می شود، تفسیر می کند و مسائل مهمی که مرز آزادی و اذیت را تشکیل می دهند، برجسته می کند. چگونه قوانین پناهندگی تبعیض را تشخیص داده و حمایت بین المللی در برابر آزار و اذیت را شایسته نمی داند؟ آیا پناهندگان می توانند از معضلاتی که زندانیان درگیر آنان هستند، دوری کنند. مانند اینکه هویت و اعتقاداتشان را انکار کنند و یا با اذیت و آزار مواجه شوند و آیا اعمال یک دیدگاه اخلاقی آسیب جدی یا شدیدی را به همراه خواهد داشت؟ چه تفاوتی باید بین دولت های مذهبی که مذهب خاصی را از طریق قوانین شرعی و یا دیگر قوانین مذهبی مبنای دولت قرار می دهند، [با دیگر دولت ها] قائل شد؟ آیا آزار و شکنجه می تواند توسط عاملان غیر دولتی یا افراطیان مذهبی اعمال شود و آیا خشونت های فرقه ای غیردولتی به قوانین پناهندگان مربوط می شود؟ قسمت سوم مقاله بر روی ارتباطات درهم آمیخته میان دین، سیاست، اقتصاد و فرهنگ در پرتو توجه به این واقعیت که مذاهب از پیروان خود انجام برخی از اعمال را می خواهند و برخی از استانداردهای رفتار اجتماعی را [برای آن ها] تعیین می کنند، تمرکز می کند. این بخش ارتباط بین دولت ها و مذاهب را مورد بررسی قرار می دهد و بررسی می کند آیا و چگونه حقوق بین الملل پناهندگان مدارای دینی و تنوع مذهبی را ترویج می کند.

-

صفحات 175-192هدف من در این تحقیق تمرکز بر ایده بحران معنوی در عرصه حقوق بشر است. موضوعی که من آن را مورد بحث قرار می دهم به مجموعه ای اساسی از مسائلی مرتبط می شود که به هدف حقوق بشر، پایه اخلاقی آن ها و زمینه متافیزیکی غایی آن ها مربوط می شود. به شکل ساده تر این پرسش را مطرح می کنم که آیا در افراد نوع بشر چیز خاصی وجود دارد که آن ها را مستحق داشتن حق می کند؟ برخی از استدلال ها مانند عامل انسان، کرامت و قانون طبیعی کاملا انتزاعی هستند. بنابراین می توان چنین فرض کرد که چون مسئله اهمیت کاربردی زیادی ندارد، این استدلالات مرتبط نیستند. اما این فرض کمی عجولانه است، زیرا تعیین پایه و اساس حقوق بشر به معنی تعیین مشروعیت خود حقوق بشر در عرصه بین المللی است. من دیدگاه عملگرا ایگناتیف را که می توان به صورت یک جمله کلیدی خلاصه کرد در نظر می گیرم: «بدون هولوکاست اعلامیه حقوق بشر وجود نداشت. به خاطر هولوکاست، هیچ اعتقاد بی قید و شرطی در این اعلامیه وجود ندارد.» و دین داری استاک هاوس در دین و حقوق بشر توسعه یافته است: متکلمان دینی. هدف من این است که هر دو دیدگاه را بررسی کنم. هم دیدگاه ایگناتیف که از پرداختن به زمینه های مذهبی حقوق بشر دوری می کند و یک دیدگاه با پایه های سکولار با ایده عاملیت انسان ارائه می دهد و هم دیدگاه مکس استاک هاوس که بر خلاف ایگناتیف از اخلاقی دینی به عنوان پایه های حقوق بشر دفاع می کند. اول از همه از طریق این تجزیه و تحلیل، قصد دارم اشاره کنم در حالی که از یک سو احترام به هم نوعان ما نیازمند یک رویکرد محبت آمیز است و تعهد ما به حفظ نوع بشر نیازمند تقویت توسط ایمان دارد؛ از سوی دیگر پایه گذاری حقوق بشر در دین بسیار خطرناک است و ممکن است درگیری های خشونت آمیز میان مذاهب مختلف به وجود آورد. دوما به انتقاد از دیدگاه ایگناتیف می پردازم، چرا که دفاع از حقوق بشر به عنوان ابزار عملگرایانه، در زمینه های عملی بسیار ضعیف است و نظام حقوق بشر نیازمند مبانی اخلاقی و متافیزیکی است که به طور جهانی شناخته شده باشد و به اجرا درآمده باشند. سوما و در نهایت با استفاده از مفهوم رالز در خصوص همپوشانی اجماع، قصد من نشان دادن عدم نیاز به توافق بر سر «بنیان های واحد» می باشد. در نظر گرفتن یک بنیان واحد توانا و معتبر برای حقوق بشر، ریسک پذیر است. در حالی که یک رژیم حقوق بشری بر بنیان های چندگانه استوار است. پذیرش حقوق بشر با بنیان های چندگانه توسط ما به پذیرش وسیع تر آن توسط مردم کمک می نماید. اگر به علت گوناگونی به طور عمومی از حقوق بشر دفاع کنیم، به درستی ثابت می کنیم که هیچ پایه متافیزیکی مناسبی وجود ندارد.دلیل خوبی برای آنکه که چرا ما نیازمند زمینه های حقوق بشری در هر متافیزیک خاص نیستیم می تواند این باشد که آن ها هم اکنون نیز به بسیاری از متافیزیک ها متکی هستند و در حال حاضر می توانند از منابع بیشتری بهره ببرند. از این رو ارزشمند و عاقلانه است که از ادعاهای غیر انحصاری متکثر مرتبط با راه هایی که حقوق بشر [به واسطه آن ها] به طور قانونی پایه گذاری می شود، استقبال کرد. برای مثال عاملیت انسان، کرامت انسانی، ایجاد برابری، نمونه هایی از مبانی مختلفی هستند که منحصر به فرد و ناسازگار با دیگری نیستند.

-

صفحات 193-203در مقاله حاضر، گفته ای از متکلم و نظریه پرداز حکومتی، جورج ویلهلم فردریش هگل در صدر مقاله آمده است. هگل اصلاحات را گذاری از جزم گرایی به سمت عقلانیت در دین می دانست که با تثبیت حکومت نوین سکولار در اروپا همزمان گردید. این مقاله استدلال می نماید که گرچه حقوق بشر به عنوان تمایل یا محتوای اخلاقی حکومت عقلانی نمودار می گردد، اما پیامد یا مکملی را برای دین ارائه نمی دهد. در واقع این حقوق غالبا اصول محوری اکثر ادیان عمده را نقض یا نفی می کنند. استدلال مربوطه آشکار است: به نظر من نمادهای اصلی دینی یعنی تکلیف و وحدت تکلیف یکی نسبت به دیگری و وحدت با خداوند در حقوق بشر کنار گذاشته می شوند. حقوق بشر روابط تکلیفی را تبدیل به نظام هایی از مالکیت و دین می کند (من دیگر نسبت به تو تکلیفی ندارم؛ بلکه تو به من مدیونی). این حقوق رابطه ای را بین دولت و فرد به گونه ای آرمانی نشان می دهد که اساسا با مفاهیم وحدت مغایر است. این استدلال تحت چهار عنوان پیش می رود: نخست من نگاهی به آزادی دارم و از نظریات هگل در این مورد استفاده می کنم که حقوق بشر باید ابزاری برای اخلاقیات دینی در یک حکومت سکولار تلقی شود. ثانیا من برای مفهوم جلوه الاهی در قالب گناه و تکلیف، به فروید و لویناس اشاره می کنم؛ من مختصرا بیان مذهبی این مفاهیم را با آنچه در گفتمان حقوق بشر یافت می شود مقایسه می کنم. ثالثا بخشی از مقاله در باب «جامعه» استدلال می نماید که این مفهوم در گفتمان حقوق بشر صرفا نادیده گرفته نمی شود، بلکه فعالانه تضعیف می گردد. نهایتا من نگاهی به نظریه و عملگروی حقوق بشر در قالب نظامی از خویش و حاکمیت از طریق قانون و حکومت خواهم داشت. این استدلال ناسازگاری بین حقوق بشر و دین را به عنوان موضوعاتی مربوط به اعتقاد فردی در نظر نمی گیرد، با این وجود رقابت بین رهنمودهای هنجاری در مورد رفتار و خودشناسی را که در حوزه عمل بر هر یک تاثیر می گذارد، تشخیص می دهد.

-

صفحات 205-220متکلمانی که توجه خود را به ملاحظات اجتماعی اختصاص داده اند، این را می دانند که تصویر مسیحیت از رستگاری شامل یک تعهد اخلاقی است و به مراتب فراتر از مرزهای خوشبینی است. قلب این تصویر، ایده پادشاهی خدا به عنوان تحقق ارزش های خاص (صلح و عدالت) و تجدید ساختار بشریت است که ملهم از برادری و همبستگی می باشد. افزایش روابط انسانی یکی از ویژگی های برجسته جهان امروز است که توسعه خود آن همراه با پیشرفت تکنیکی می باشد. تبادل دوستانه چنین ایده هایی در میان مردم از طریق چنین پیشرفت هایی به دست نمی آید، بلکه این پیشرفت ها در عمیق تر شدن روابط افراد جامعه است و این امر مستلزم احترام متقابل نسبت به شان معنوی آن هاست. مفهوم منافع مشترک در این مقاله به روش های مختلفی تعریف شده است.

-

صفحات 221-240این مقاله ارتباط بین دین و حقوق بشر را که در قالب کار و ماموریت گروه های صلح طلب مسیحی و تیم های صلح طلب مسلمان تجسم یافته است، بررسی می کند. این نوشتار مدل هایی مانند نظریه های مارگارت کک و کاترین سیکینک را برای ارائه چارچوبی برای درک، نقد و نحوه کارکرد CTP و MPT برای مقایسه ارائه می دهد. گروه های CTP و MPT از طریق قرار دادن خود در موقعیت های جنگی به منظور کاهش تمام اشکال خشونت علیه غیرنظامیان با خشونت مبارزه می کنند. این جنبش در دهه 1980 بر اساس رویه «کلیسای صلح» مسیحیان متولد شده و این حرکت تا جرقه تشکیل جنبش های کمتر شکل یافته صلح طلبان مسلمانان گسترش یافته است. در حال حاضر دو گروه از طریق تمرینات مشترک و اهداف آموزشی همکاری می کنند. CTP و MPT یک مثال منحصر به فرد از ادغام دین و حقوق بشر را ارائه می دهند. در حالی که CPT به طور وسیع کار کرده است و تجربیات خود را به طور گسترده ای منتشر کرده است، هر دو گروه نمونه های همکاری بالقوه گروه هایی هستند که به منظور پیشبرد حقوق بشر از مذهب استفاده می کنند. از آنجایی که CPT ساختار سازمانی شکل یافته تری دارد، این مقاله بر روی این گروه تمرکز دارد تا اصولی که هر دو طرف به آن عمل می کنند را مشخص کند. به همین ترتیب، پرسش هایی درباره نحوه ارتباط بین حقوق بشر و مذهب در نحوه عملکردCPT بسیار مشخص است. هدف اصلیCPT کاهش خشونت علیه غیرنظامیان از طریق قراردادن خود در معرض خطر است؛ به علاوه، CPT از طریق ایجاد شبکه هایی از جوامع مذهبی، سازمان های حقوق بشری و غیره تلاش می کند تا تغییرات کلانی را صورت دهد، حتا اگر بیشترین فعالیت ملموس آن ها بسیار کوچک باشد. CPT و MPT به وضوح از بنیاد عمیق مذهبی بهره می گیرند. تاکید بر انعکاس عادت های معنوی، تجربه معنوی جمعی و عبادت عمومی و خصوصی این بنیان ها را برجسته می کند. برخی دیگر از تاکتیک های کوچک این گروه ها عبارتند از اعتراضات مدنی، حفظ هویت غیر پرتستانی یا تبلیغی، اجتناب از ادامه بی عدالتی و اجرای آموزه ها و نمونه هایی از صلح طلبی از حضرت محمد و حضرت عیسی. بخشی از پارادوکس ناراحت کننده که برای مقاله ناگزیر است، مرتبه ای ست که به نظر می رسد در میان گروه های همجنس و مشابه، موثرتر باشد. داستان تام فاکس (عضو CPT) این اصل را شرح می دهد. در حالی که اخیرا مدرسه بهداشت بلومبرگ دانشگاه جان هاپکینز میزان مرگ و میرهای عراق را از سال 2003 بیش از 650000 نفر اعلام کرده است، ربودن و مرگ فاکس در سال 2005 به میزان قابل توجهی [بیش از خبر کشتار عراق] توجه رسانه های غربی را جلب کرده است. رسانه هایی که به وضوح تبعیض آمیز عمل می کنند و توجه افکار عمومی، مواردی هستند که گروه هایی مانند CPT به منظور جلب توجه و ایجاد تغییر در شرایط درگیری باید با هر دوی آن ها مبارزه کنند و همچنین در شرایطی از آن ها استفاده کنند. بدین منظور، گروه هایی مانند CPT و MPT تلاش می کنند تا موانعی را که رسانه ها و دولت های قدرتمند آن ها را ایجاد کرده اند، کنار بگذارند. این مقاله به دنبال جدی گرفتن شان و منزلت تلاش-های مسلمانان و مسیحیان است.

-

صفحات 241-256در نیمه اول این مقاله من اهمیت صلح را به عنوان آرمان سنت لیبرال بررسی می کنم. من با ترسیم سیر تکاملی این آرمان از طریق آثار هابز، روسو و کانت نشان می دهم که چگونه این آرمان که روابط انسان نباید بر نیرویی متکی باشد، در قلب سنت لیبرال قرار دارد. با این حال، در میان برخی از لیبرال های معاصر، به ویژه کسانی که تحت تاثیر جان رالز قرار دارند، پیشنهاد می شود که صلح لیبرال تنها میان افرادی وجود دارد که تمایل به جدا سازی رادیکال حوزه های مذهبی و سیاسی دارند و دین را صرفا به حوزه خصوصی مختص می دانند. در نیمه دوم این مقاله من این ادعا را مورد سوال قرار می دهم و استدلال می کنم که صلح لیبرال لزوما شامل خصوصی سازی دین نیست. من معتقدم که این سوال در شرایط واقعی بهتر بررسی می شود تا در یک شرایط انتزاعی و من بر متفکر خاصی متمرکز هستم که کاملا مخالف خصوصی سازی دین است: سید قطب. در ظاهر ممکن است چنین به نظر برسد که صلح دراز مدت میان سکولارهای لیبرال و یک متفکر مانند سید قطب امکان پذیر نیست، زیرا به نظر می رسد که او یک دشمن کینه توز علیه دموکراسی لیبرال است. بخشی از تاثیرگذارترین و رادیکال ترین اثر او، نقطه عطف عملکرد او، به عنوان بخشی از یک نوشتار در باب یک اختلاف نظر در برابر آن دسته از مسلمانانی بود که باور داشتد قرآن فقط جهاد دفاعی را تضمین می کند نه جهاد ابتدایی را. قطب چنین استدلال می کند که اسلام یک پیام جهانی را ارائه می دهد و در قلب این دین جهانی، نفرت از استبداد است. بنابراین، مسلمانان نباید فقط برای دفاع از سرزمین اسلامی در مقابله از حمله دفاع کنند، باید در مقابل استبداد در هر جایی مبارزه کنند. قطب استبداد را جامعه ای تعریف می کند که مردم آن حاکمیت خدا را قبول نداشته باشند. اکنون، از آنجا که جوامع لیبرال غربی بر پایه ایده حاکمیت مردمی و خودمختاری هستند، ممکن است چنین به نظر برسد که قطب بر مشروعیت مسلمانانی که جهاد خشونت آمیز علیه دموکراسی های لیبرال غربی را انجام می دهند، استدلال می کند. او توسط بسیاری از لیبرال های غربی و جهادگرای معاصر اسلامی چنین شناخته می شود. با این حال، من استدلال می کنم که این نتیجه گیری شتابزده برای جلب توجه است، زیرا مشخص است که هدف اصلی قطب، رژیم های استبدادی ظالمانه در جهان عرب است و دیدگاه های وی نسبت به جوامع دموکراتیک لیبرال غرب، بسیار مبهم است. اولا روشن نیست که سنت لیبرال به نحوی که قطب آن را رد می کند، واقعا مبتنی بر ایده حاکمیت انسان باشد، زیرا این سنت قانون طبیعی تراوشاتی داشته است و در میان لیبرال ها یک توافق قوی وجود دارد که یک جامعه مشروع توسط قانون اداره می شود و نه خواسته های خودسرانه انسان ها. دوم، اگر چه قطب با ایده حاکمیت مردمی مخالف است، به نظر می رسد که خود چیزی شبیه قرارداد اجتماعی ارائه می کند. زیرا معتقد است که اگرچه تمام این قوانین در نهایت از خدا می آیند، قانون اسلامی نمی تواند به وسیله زور اعمال شود و بنابراین قبل از اینکه جامعه ای بتواند توسط قوانین الاهی اداره شود، نیاز به یک جامعه اسلامی است و تنها از طریق اعطای آزادی از جانب قانون به اعضای جامعه می تواند وجود داشته باشد. در نهایت، دیدگاه های قطب درباره هرمنوتیک نیز نشان می دهد موقعیت های بسیار لیبرال تری در مقایسه با آنچه به او نسبت می دهند، ارائه می دهد.

-

Pages 3-30The main question of this article is this. Does religion itself play a role in “political violence”? After clarifying the meaning of relevant terms such as “religion”, “religious violence”, “secular violence”, “voluntary action” and “political violence”, I will examine two arguments that can be formulated in favour of the claim that religion itself is the unique cause of the so-called religious type of political violence, concluding that both of these arguments are subject to criticism and neither is successful in supporting that claim. Then I will suggest my own explanation of the real cause and origin of political violence in general and its proper solution. I will also conclude that the well-known distinction between religious and secular violence is not tenable.Keywords: Religious Violence, Secular Violence, Political Violence, Hisory of Religion, Interpretation of Religious Texts

-

Pages 31-48So long as there is law there can be no universal human right to peace. This is because legalized violence, whether in threat or in deed, constitutes the very antithesis of peaceful relations from the point of view of those whom law represses. Law cannot define peace as the absence of all violence—and still less as the absence of all legalized suffering—without gainsaying justice, for as Pascal says, “Justice without might is helpless; might without justice is tyrannical.” Although legal outcomes, like falling boulders and pouncing lions, can always be imputed to historical causes, experience teaches that legal actors generally seek to legitimate their deeds by grounding the law in some non-causal narrative of the right or the good. According to a tenet of political liberalism that can be traced to Descartes’ discovery (or invention) of the irreducible “I” that thinks, the legitimacy of law’s narrative is both given and taken by free and rational politico-legal subjects. In truth, however, the Western philosophical tradition gives us two separate grammars for discussing what it takes to be two different kinds of rational subjects: the causal subject and the grounding subject. The causal subject stands in a relation to the world. Acting strategically as the cause of effects, it uses the object world and other human beings as means to its ends. But the causal subject is also itself caused: its desires and actions are effects of history in the largest sense of the word. Such a one is fated by grammar and custom to become an object and a means in its own right: an object for scientific inquiry and knowledge, for example, and, more generally, a means to the ends of other causal subjects. From the standpoint of the causal subject, there can be no human right not to use or be used as a means.

Unlike the causal subject, the grounding subject is supposed to be a genuine origin rather than a mere link in an infinite chain of causes and effects. In Greek terms, this subject is an archē as opposed to an aitia. It also corresponds to the original Latin meaning of the word “sub-ject”: it is thrown (jacere) under (sub) its world as (not in) an unmediated relation to its projects. This second kind of subject has gone by many different names, including “soul” (Plato), “freedom” (Kant) and “Spirit” (Hegel). In one way or another, the idea of the grounding subject performs its primary task within the moral sphere: it is supposed to provide a secure foundation which explains how it is possible for its doppelganger, the causal subject, at once to accomplish something in the world and to refute Plautus’s notorious argument that man is wolf to man. If the causal subject reacts in the manner of an animal, then the grounding subject allegedly responds in the manner of an animal rationale. If the causal subject produces effects, then the grounding subject is supposed to create and bear responsibility for those effects.

Given the foregoing distinctions, the most pressing juridical and moral question facing twenty-first century humanity seems to be: How can law and politics become at once effective and just, coercive and compassionate, responsive and responsible? How, in short, is it possible (to borrow Kant’s somewhat quaint terminology) to use oneself and other human beings simultaneously as ends and as means? But here, as elsewhere in philosophy, appearances can be deceiving, for this question presupposes far too much.

This paper investigates the strong connection between the foregoing concepts of subjectivity and the notion of a just peace. The question is not, “Are there rational subjects and can they found something new, such as a just peace?” Instead, the question at the heart of the matter is how something as flimsy and ephemeral as an “idea” could ever found anything at all. I will attempt to unmask the terrible tensions or contradictions between justice and ethics, freedom and responsibility, and reason and compassion, and trace them to their origin: the will (or desire) to deny tragedy. I claim that the concept of the grounding subject represents a desperate and ultimately futile attempt to repress awareness of (and evade personal responsibility for) the essential sadness and tragedy of the world. Reason and faith provide the human body with a thin tissue of grounding statements comprised of symbols and images. At best these symbols and images are mere stimuli: action-triggers that will never adequately span the vast existential distance separating the grounding subject from the causal subject, our ends from our means, our words from our deeds, and, more generally, human suffering from the endless secular and religious casuistries we offer to justify it.Keywords: peace, Universal Human Right, Law, Philosophical Tradition, Subjectivity -

Pages 49-64This paper will seek to present an understanding of the historical conditions that make possible a convergence of the selected religious teachings and human rights, and ask the question if such a convergence can operate successfully within a hierarchal bureaucracy such as found in government or institutional religion. The paper will look at three specific case studies where there has been a convergence of human rights and religion and the resulting struggle to influence the behavior of the state: 1. the example of Christian liberation theology in South America in the 1960s and 70s. 2. The example of the movement Rabbis for Human Rights within the Israeli milieu from its founding in 1988 to the present. 3. The example of CAIR –The Council on American-Islamic Relations– which presently operates in the U.S.

Within the teachings of most great religious movements are found principles of behavior that support the concept of universal human rights. However, these principles are overshadowed when the religious teachings are enlisted to the needs of institutions, be they of the state or established religious hierarchies. The needs of institutions and hierarchical bureaucracies do not reflect universal human rights and the principles of behavior that underpin them. Rather, such institutions reflect the particular needs of interest groups and elites. These elites often are able to use ideology (which may be religious in nature) to cause their own special interests to be substituted for a community’s more general needs and interests. As the rules of behavior narrow to accommodate institutional and bureaucratic dictates, universal human rights becomes the cause of minority groups and others on the margin of society seeking to reinterpret and broaden the definitions of what is humane and proper behavior. It is within this struggle to reinterpret rules of behavior along the lines of universal human rights that a convergence between religious teaching and human rights becomes most possible. But once again, this will happen as an alliance of those outside the dominant power structure. The three case studies given above demonstrate how this struggle from the margins has been fought in three contemporary arenas. A reasonable conclusion drawn from this is that supporters of universal human rights seem, ironically, condemned to never to attain the structural power necessary to enforce, on a universal scale, the practice of their principles. For, no such structural power exists that is designed to realize such universal ends. Thus, even on those rare occasions when champions of human rights manage to attain positions of power, they are always restrained, co-opted, or otherwise compromised by the institutional and bureaucratic matrices of power–all of which are typically designed to promote and protect particular, and not universal, interests. Thus, from an historical prospective, those promoting universal human rights, even when allied to or inspired by religious teachings, are condemned to always fight as outsiders. For to move inside is to transform universal principles into special interest dictates.Keywords: Problems in Organizational Structure, Religious Study, human rights, Historical Conditions -

Pages 65-84Europe is a constellation of liberal democracies characterised by the conviction that the public sphere should be strictly secular and should rule out religious arguments from the realm of public reason. We may call this attitude ‘the liberal confidence.’ In the last years, the liberal confidence has been put under considerable strain by a number of cases such as the scarf, the cross in the classroom or the Mohammad cartoon saga. It quickly appeared that the liberal confidence could not provide convincing arguments to decide those issues. The principal explanation for the lack of a convincing liberal position is reflected in the dogmatic character of the liberal confidence which assumes, instead of articulating a sound justification, that religion, religious symbols and religious opinions are best kept away from our sight. This artificial situation creates more tensions than it solves and it is time to review this fundamental weakness in the liberal strand of thought. This problem raises various philosophical issues. First, it points to a serious epistemological problem, namely what is the status of religious beliefs in the formulation of public policies? Second, it raises a political issue regarding the relationship between political and religious institutions in European polities. Third, it brings back to the public forum the fundamental ethical question –How should we live?- by asking how can we possibly share the same polity without engaging in these issues in comprehensive terms (that is, in a way that takes seriously everyone’s religious and other beliefs alongside with other types of beliefs).Keywords: Europe, human rights, democracy, Liberal Approach, Religious Opinions

-

Pages 85-112I have been in exile for a long time, and I was amazed at the resilience, intelligence, strength and ability of the Afghan women that I met who came from inside the country and around the world. These women, I promise, can rebuild the country with no problem. (Bernard et al, 2008: 150) In this paper I propose to examine the role played by women in post-conflict scenarios, especially with regards to peace-keeping and nation building. I would like to begin with a general statement about the important and equal role of women in society, a principle which is enshrined in both international human rights documents such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It is also a principle that is accepted by the major religions, including Islam. The proposed title of the paper takes its inspiration from the following quote:Few policymakers responsible for nation-building would argue against the ultimate goal of establishing equitable, democratic and egalitarian societies in which the human rights of women are respected. Many however, express the fear that pursuing that goal “too soon” may rock the boat, and that in dealing with a boat so shaky that it may capsize anyway, you just can’t take the risk.

This paper seeks to determine what role women should play in post-conflict scenarios, without “capsizing the boat”. It questions to what degree women’s involvement must be postponed in order to first “stabilize the situation”. Some would argue that given the various advantages in women’s involvement sooner rather than later, that their involvement ought not to be postponed. The paper will particularly draw upon the involvement of women in Afghanistan. However, Afghanistan itself provides examples of the danger and difficulty of promoting women’s involvement in nation-building. For example, as recently as Sunday 29th September 2008 it was reported that an iconic Afghan policewoman, Malalai Kakar, had been shot and killed, and that the Taliban had claimed responsibility for her death. This was not the first instance of a woman in Afghanistan’s post-2001 police force being directly targeted for assassination. The question these incidents raise is whether an emphasis on promoting the participation of women in the Afghani police-force is premature: is this an example of “rocking the boat” or is this all part and parcel of nation-building? The proposed broad outline for the paper is as follows: Introduction and basic premises: The equality of women and the role of women in society: general legal, social and religious principles; Women and nation-building: definitions, general principles, international documents and statistics; Afghanistan: processes and problems – historical context and modern issues; Conclusion recommendations for Afghanistan in particular and for women in nation-building in a more general sense.Keywords: Nation Building, human rights, Afghan Women, Women’s Role -

Pages 113-139Recognising the inherent problems associated with the international human right to freedom of religion or belief, this article proposes an alternative approach to the right.

One can begin to address the right by clarifying the importance of knowledge and the role that it plays when combined with power. Adopting notions proposed by M. Foucault provides the groundwork for a transgressive interpretation of religion or beliefs such as to account for assertions of a religion or a belief as part of the ongoing social discourse. Manifestations of a religion or belief need not be understood as a struggle between the individual and state, but rather within a broader framework. Consideration could be made of additional factors towards understanding a belief, including the assertions of a believer, without necessarily weighing the merits of the belief.Keywords: Foucault, Religion, Freedom, Alternative Approach -

Pages 141-174The right to freedom of religion or belief has been well-established in human rights instruments since the inception of the modern era of international law. However, while inner freedom of belief has been uncontested, the ability to manifest those beliefs publicly has been made subject to limitations for certain purposes which include public safety and order, health, morality and the fundamental rights and freedoms of others. The degree to which such restrictions on religious practice may be permissible under the rubric of international human rights law has been and continues to be under debate. International refugee law has played an important role in safeguarding religious freedom, as persecution for reasons of religion is one of the five grounds enumerated in the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. To what degree are restrictions on religious practice permissible and at what point do such restrictions rise to the level of persecution meriting international protection? An examination of the refugee jurisprudence of States adjudicating religion-based claims will help illustrate the nebulous boundaries of the definition of persecution in the context of religious practice and identify some of the factors and trends which influence refugee decision-making.

Part I will provide an overview of international refugee law as it relates to religion and describe the Westphalian context under which it was constructed. The modern era of international law was strongly influenced by wars of religion and the principle of cuius regio, eius religio – whose the rule, his the religion – which emphasized respect for national sovereignty and non-interference in religious affairs of the state as essential to international stability. International refugee law, developed largely in response to World War II and the Holocaust, attempts to balance respect for national sovereignty with humanitarian protection concerns by only applying to persons outside their country of origin. Part II will discuss refugee jurisprudence interpreting the point at which religious restrictions constitute a well-founded fear of persecution and highlight issues which form the boundaries of persecution. How does refugee law distinguish discrimination, which does not merit international protection, from persecution? Should refugees be able to avoid the prisoners’ dilemma of either renouncing their identity or beliefs or face persecution and should the imposition of a moral view constitute serious or grave harm? What deference should be given to religious States who advocate a certain religion as an affair of the State, whether through Shari’a or other religious laws? Can persecution be caused by non-State actors or religious extremists and is non-State sectarian violence a matter for refugee law? Part III will reflect on the inextricable links between religion and politics, economics and culture in light of the fact that religion demands practice by adherents and dictates standards of social conduct. It will discuss the relationship between States and religion and consider whether and how international refugee law promotes religious toleration and pluralism.Keywords: Refugees, Religious Persecution, Restrictions, Pluralism -

Pages 175-192My intention in this research is to focus on the idea of spiritual crisis in human rights arena. The topic I shall be discussing concerns a basic set of issues dealing with the purpose of human rights, their moral foundation and their ultimate metaphysical ground. Simply put I shall be asking whether there is something special in human beings which entitles them to rights. Some arguments such as human agency, dignity and natural law tend to be quite abstract. It could therefore be tempting to assume that the issue, being of not much practical importance, is not relevant. But this would be a rush assumption because determining the foundation of human rights means determining the very legitimacy of human rights themselves in the international arena. I will consider Ignatieff’s pragmatic point of view that can be summed up with a catch phrase: “without the Holocaust no Declaration, because of the Holocaust, no unconditional faith in the Declaration either” and Stackhouse’s religious one developed in Religion and Human Rights: a Theological Apologetic. My purpose is to analyse both Ignatieff’s view, that avoids contentious religious ground for human rights and offers a secular ground designed with the idea of human agency, and Max Stackhouse who, instead, defends the idea of a theological ethic as religious ground for human rights. First of all, through this analysis I aim at pointing out that while on the one hand the respect for our fellow human beings needs a reverential attitude and our commitment to protect our species needs to be sustained by some faith; on the other hand grounding human rights in religion is extremely dangerous and may imply violent clashes between different religious faiths. Secondly, I also aim at criticizing Ignatieff’s view because a defence of human rights as pragmatic instruments on pragmatic grounds seems to be too weak and human rights regime needs moral and metaphysical foundations to be universally recognized and implemented. Thirdly and ultimately, using Rawls’s concept of overlapping consensus I aim at showing the unecessity to agree upon a “single foundation”. A single foundation risks to be authoritative, whereas, what a human rights regime relies on is a plural foundations. If we arrive at respecting human rights on a plurality of grounds, then we are making them more broadly acceptable to people. If we publicly defend human rights for a plurality of reasons, we are rightly proving that there is no “proper” metaphysical foundation.

A good reason why we do not need to ground human rights in any particular metaphysics can be that they are already grounded in many metaphysics and can already derive sustenance from many sources. Hence, it would be worthwhile and wise to welcome a plurality of nonexclusive claims concerning the ways in which human rights can legitimately be grounded. Human agency, human dignity, equal creation are, for instance, some examples of different foundations that are not mutually exclusive.Keywords: human rights, Political Theory, Spiritual Crisis, Human Dignity, Moral Foundation -

Pages 193-203The present paper takes as its moniker an assertion of that theologian-cum-state theorist, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel saw the Reformation as a moment of transition from dogma to reason in religion, concomitant with the establishment of the modern secular state in Europe. This paper will argue that whereas human rights appear as the ethical content or desire of the rational state, they do not offer a simple corollary or complement of religion; indeed they tend to reverse or negate principles that are central to most major religions. The argument is straightforward: I suggest that core religious symbologies of obligation and community—the obligation of one toward another and the community in God—are vacated in human rights. Human rights transform relations of obligation into systems of ownership and debt (I am no longer obliged to you; rather you are indebted to me). They idealise a relation between the state and the individual that is fundamentally hostile to notions of community. The argument proceeds under four headings: first I look at ‘freedom’—drawing on Hegel for the thesis that human rights be read as a vehicle of religious ethics in a secular state. Second, I refer to Freud and Levinas for the sense of the divine expressed through (or manifest in) guilt and ‘obligation’; I contrast briefly the religious expression of these notions with that found in human rights discourse. Third, a section on ‘community’ argues that this is not merely ignored in human rights discourse, it is actively undermined. Finally, I look at the contemporary practice and theory of human rights envisaged as a system of self and sovereignty channelled through ‘law’ and the state. The argument does not assume incompatibility between human rights and religion as matters of personal belief—it does however identify rivalry between the normative directives on behaviour and self-understanding that inform each as a matter of practice.Keywords: Ethics, human rights, Religious View, Freedom, Obligation

-

Pages 205-220Theologians whose attention is devoted to social considerations know that the Christian picture of salvation carries with it an ethical commitment which goes well beyond the bounds of intimism The heart of this picture is the idea of the Kingdom of God as the fulfilment of certain values (peace and justice) and recomposition of a humanity imbued with new brotherhood and communion. The increase of human relationships is an outstanding feature of today's world, whose development is itself fuelled by concomitant technical progress. Fraternal exchange of ideas between peoples is not achieved via such progress, but more deeply in the community of persons, and this demands reciprocal respect for their full spiritual dignity. The concept of the common good is elaborated and formulated in several ways in this article.Keywords: human rights, common good, Catholic Point of View, Theological Foundation

-

Pages 221-240This paper will explore the links between religion and human rights as embodied in the work and mission of the Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT) and Muslim Peacemaker Teams (MPT). The paper compares models such as those of theorists Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink in providing a framework in which to understand, critique and build on the work of CPT and MPT. The CPT and MPT groups “get in the way” of violence through placing themselves in conflict situations for the purpose of reducing all forms of violence against civilians. Born out of the “Peace Church” traditions of Christianity in the 1980s, the movement has expanded to spark formation of the less formalized Muslim Peacemaker Team. The two groups now collaborate through shared training exercises and goals. CPT and MPT present a unique example of the integration of religion and human rights. While CPT have worked more extensively and published their experiences more broadly, both groups exemplify the potential synergy of groups who draw on religion in order to advance human rights. As CPT has a more formalized organizational structure, the paper focuses on this group in order to lay out principles from which both operate. As such, the questions of how human rights and religion are interconnected become very clear in the work of CPT. CPT main goal is to reduce violence against civilians through putting themselves in harms way; in addition, CPT also conscientizes the broader public through publishing accounts of their work, particularly on the internet. CPT works to establish networks of faith communities, human rights organizations, etc. to effect macro-level change, even as their most tangible work is very micro-level. CPT and MPT clearly operate out of a profoundly religious foundation. An emphasis on regular spiritual reflection, communal spiritual experience, and public and private prayer underlines this. Some of the groups’ other specific micro-level tactics include civil protest, maintaining a non-evangelical or proselyte identity, avoiding perpetuation of injustices and living out the teachings and examples of peacemaking from the Prophet Mohammed and Jesus. Part of the troubling paradox that necessitates the paper is the degree to which conscientization proves most effective among homogeneous and similar groups. The story of CPT member Tom Fox illustrates this principle. While recent John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health estimates place the number of Iraqi deaths at more than 650,000 since 2003, the abduction and death of Fox in 2005 captured a tremendously disproportionate amount of Western media attention. The obviously discriminatory media and general public attention is something that groups like CPT must both combat and utilize in order to draw attention to and bring change surrounding conflict situations. In so doing, groups like CPT and MPT seek to bridge the barriers that the media and powerful nation-states perpetuate. This paper seeks to take seriously the dignity of both Muslim and Christian efforts.Keywords: Peacemaking, Christian, Muslim, Reduce Violence

-

Pages 241-256In the first half of this paper I examine the importance of peace as an ideal in the liberal tradition. I begin by tracing the evolution of this ideal through the works of Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau and Kant, showing how the idea that relations between human beings should not be based upon force lies at the heart of the liberal tradition. Amongst some contemporary liberals, however, especially those influenced by John Rawls, there is a suggestion that liberal peace is only possible between individuals who are willing to make a radical separation between the religious and political domains, assigning religion exclusively to the private domain. In the second half of this paper I question this claim and argue that liberal peace does not necessarily involve the privatization of religion. I believe that such question are better discussed in concrete rather than abstract terms and I so focus on a particular thinker who is clearly against the privatization of religion: Sayyid Qutb. On the surface it might seem that long term peace between secularist liberals and a thinker like Qutb would be impossible, because he seems to be an implacable enemy of liberal democracy. His most radical and influential work, Milestones, was, in part, written as a polemic against those Muslims who believed that the Koran only sanctions defensive Jihad and not offensive Jihad. Qutb argues that Islam offers a universal message and at the heart of this universal faith is a hatred of tyranny. Therefore, Muslims must not just struggle to defend Islamic lands from attack but must fight against tyranny wherever it occurs. And Qutb identifies tyranny with any society where human beings have usurped the God’s sovereignty. Now, in so far as western liberal societies are based on the idea of popular sovereignty and self-determination this might seem to suggest that Qutb is arguing for the legitimacy of Muslims waging violent jihad against western liberal democracies, and this is how he is often read, both by many western liberals and by contemporary Islamic jihadists. I argue, however, that this is a hasty conclusion to draw, for it is clear that Qutb’s primary target was oppressive authoritarian regimes in the Arab world and his views towards western liberal democratic society were far more ambiguous. Firstly, it is not clear that the liberal tradition is really based upon the idea of human sovereignty in the way Qutb rejects it, for this tradition is seeped in the natural law tradition, and there is a strong agreement amongst liberals that a legitimate society is one ruled by law and not the arbitrary will of human beings. Secondly, although Qutb is opposed to the idea of popular sovereignty, he himself seems to offer an analogue of the social contract, for he believes that although all law ultimately comes from God, Islamic law cannot be imposed by force and so that before one can have a society governed by divine law there needs to be an Islamic community, and which can only come into existence through the free submission of its members to the law. Finally, Qutb’s views on hermeneutics also suggest a far more liberal position that is usually attributed to him.Keywords: Qutb, Aquinas, divine law, limits