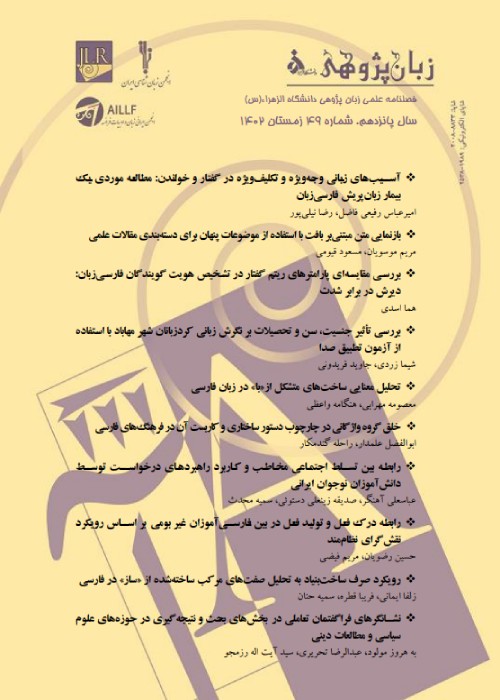

فهرست مطالب

نشریه زبان پژوهی

پیاپی 35 (تابستان 1399)

- تاریخ انتشار: 1399/06/15

- تعداد عناوین: 12

-

-

صفحات 7-34

اسم صفت ها، صفت هایی هستند که به وسیله فرایند اسم شدگی به اسم صفت تبدیل می شوند. اسم صفت و به طور کلی اسم شدگی از موضوع هایی هستند که در ساخت واژه، نحوو درمکتب های گوناگون زبان شناسی نظری مطرح شده اند. هر چند تاکنون پژوهشی در زمینه اسم صفت های زبان فارسی انجام نگرفته است. این پژوهش، برآن است تا در چارچوب نحوی برون اسکلتی بورر (Borer, 2013) به تحلیل این مقوله بپردازد. بورر (همان) معتقد است که واژه ها فاقد هرگونه طبقه واژگانی هستند و طبقه واژگانی خاص آن ها فقط در بافت نحوی مشخص می شود. وی براین باور است که اسم صفت ها از ادغام وندهای اشتقاقی با ریشه صفتی در فرایند اسم شدگی مشتق می شوند. او، همچنین، به پیروی از روی (Roy, 2010) اسم صفت ها را به دو دسته اسم صفت های کیفیت و بیانی تقسیم می کند. یافته های پژوهش نشان می دهد زبان فارسی دارای اسم صفت های پسوندی است. این اسم صفت ها به دو دسته اسم صفت های کیفیت و بیانی گروه بندی می شوند. از این نظر، یافته های پژوهش حاضر با دیدگاه های بورر در چارچوب برون اسکلتی همسو است. همچنین، نتایج پژوهش نمایانگر این دیدگاه است که زبان فارسی نوعی اسم صفت نتیجه ای نیز دارد.

کلیدواژگان: رویکرد بروناسکلتی، اسمشدگی، اسمصفت، اسمصفتکیفیت، اسمصفت بیانی، اسمصفتنتیجهای -

صفحات 35-54

بازتحلیل واژگانی، یکی از جلوه های بومی سازی است که در اثر ناآگاهی افراد از ریشه واژه، رخ می دهد. در بازتحلیل واژگانی، جزیی از وام واژه بر اساس شباهت ظاهری، با یک تکواژ یا واژه مشابه، اشتباه گرفته می شود و با آن جایگزین می شود. پدیده بومی سازی در هر زبانی با توجه به قواعد خاص آن زبان، شکل ویژه ای به خود می گیرد و در پی آن نامی مرتبط با اسم همان زبان، بر آن گذارده می شود. بنابراین دراین مقاله، بومی سازی وام واژه ها در زبان فارسی، «فارسی سازی» نام گرفته است. هدف این پژوهش، بررسی ساختاری بازتحلیل واژگانی به عنوان یکی از روش های ویژه فارسی سازی و دسته بندی آن بر پایه ساختار ارایه شده است. در همه موارد بازتحلیل واژگانی، سه مولفه مشترک (وام واژه، بوم واژه، و ویژگی های معنایی وام واژه) وجود دارد و بین این سه مولفه نیز سه رابطه (دال و مدلولی، شباهت صوری، و ارتباط مصداقی) حاکم است. رابطه سوم، یعنی ارتباط مصداقی بین مفهوم وام واژه و بوم واژه بر اساس شکل، کارکرد و یا معنای وام واژه که در مولفه سوم نمایان شده است، تغییر می کند. بر همین اساس، پدیده بازتحلیل به انواع بازتحلیل صوری، بازتحلیل نقشی و بازتحلیل معنایی گروه بندی می شود و ضمن ارایه نمونه هایی، هرکدام جداگانه مورد بررسی قرار می گیرد.

کلیدواژگان: وام گیری، فارسیسازی، بازتحلیل واژگانی، وامواژه، بومواژه -

صفحات 55-82

از آن جایی که زبان آموزان دارای پیشینه های فرهنگی متفاوتی هستند، باید از هوش فرهنگی مناسبی برای یادگیری زبان فارسی به عنوان زبان دوم برخوردار باشند. هوش فرهنگی این امکان را به زبان آموز می دهد تابا به کارگیری دانش و دقت عمل،تفاوت های فرهنگی رادریابد و در برخورد با دیگر فرهنگ ها رفتاردرستی درپیش گیرد. در پژوهش حاضر، در راستای اهمیت هوش فرهنگی در زبان آموزی و به منظور کیفیت بخشی روش تدریس زبان فارسی، الگویی به نام الگوی «هیجامد» معرفی شده است. الگوی هیجامد به نقش حواس و هیجانات در زبان آموزی پرداخته و متشکل از سه مرحله هیچ آگاهی (تهی)، برون آگاهی (شنیداری، دیداری، لمسی-حرکتی) و درون آگاهی (درونی و جامع) است. به منظور سنجش تاثیر استفاده از این الگو بر هوش فرهنگی فراگیران زبان فارسی از دو پرسش نامه هیجامد و هوش فرهنگی استفاده شد. 60 زبان آموز زن غیر فارسی زبان از 16 کشور با سطح زبانی یکسان در زبان فارسی (سطح زبان فارسی 7) به روش نمونه گیری در دسترس انتخاب شدند. آن ها پس از گدراندن 22 جلسه آموزش برای 4 گروه (هر گروه شامل 15 نفر) و در مدت زمان 6 هفته، بر اساس الگوی هیجامد مورد ارزیابی قرارگرفتند. یافته های پژوهش نشان داد که تدریس مبتنی بر الگوی هیجامد بر میزان هوش فرهنگی زبان آموزان غیرفارسی زبان تاثیر معنادار مثبت داشته است و کیفیت یادگیری زبان فارسی را از طریق ایجاد ارتباط بین فرهنگی میان مدرس و زبان آموزان افزایش داده است. بنابراین به نظر می رسد از این الگو می توان در تدریس زبان فارسی و مهارت های مربوط به آن بهره برد و درک بین فرهنگی زبان آموزان را ساده تر کرد.

کلیدواژگان: یادگیری زبان فارسی، هَیَجامَد، هوشفرهنگی، هیجان، حواس -

صفحات 83-109زبان عربی، از جمله زبانهای سامی است. به سبب آنکه، عربی زبان دین و مذهب بوده، سخنگویان بسیاری دارد. زبان انگلیسی از جمله زبانهای هند و اروپایی است. زبان انگلیسی، زبان علم و فنآوری بوده و از سوی دیگر به دلیل سخنگویان بسیار و جهانی بودناش، جایگاه ویژه ای دارد. این پژوهش، به مقایسه فرایندها در زبان عربی و انگلیسی پرداخته و قصد دارد که به بیان شباهت ها و تفاوت ها در فرایندها مشارکین اصلی و عناصر پیرامونی بپردازد. بر این مبنا، مقاله حاضر بر آن است تا به تعریف فعل و فرایند و گذرایی در دو زبان، تفاوت ها و شباهت ها در نوع فرایندها بپردازد. دستور نقش گرایی هلیدی با فرض اینکه الگوهای تجربه در قالب فرایندها و نظام گذرایی در زبان بازنمایی می شود، فرایندهای شش گانه را مطرح ساخت. فرایند اصلی به مادی، ذهنی و رابطه ای تقسیم می شوند و فرایندهای فرعی به کلامی، رفتاری و وجودی. بررسی کتاب های دستور سنتی و زبانشناسی نوین نمایانگر آن است که اختلاف دیدگاه در بیان گذرایی در اصطلاحها و نامگذاری است. تعدی و گذرایی به یک معنا مورد استفاده قرار گرفتهاند و تفاوت اساسی میان فرایند ربطی و کلامی مطرح است. در زبان انگلیسی فرایند ربطی و کلامی در قالب فرایند ربطی آورده میشود، درحالی که در زبان عربی فرایندی وجود ندارد. فرایند کلامی نیز در زبان عربی محذوف است و دارای جانشینی به اسم حرف ندا است.کلیدواژگان: زبان انگلیسی، زبان عربی، نقشگرایی، گذرایی، فرایندها

-

صفحات 111-130

پهلوی اشکانی، یکی از زبان های ایرانی است که نوشته های آن در دوره میانه زبان های ایرانی از اشکانیان، ساسانیان و پیروان دین مانوی بر جای مانده است. در دوره نو زبان های ایرانی، دیگر اثری از این زبان در دست نیست. با این همه، گویش های ایرانی نو هر یک به گونه ای دنباله یکی از زبان های ایرانی در دوره میانه و باستانی زبان های ایرانی هستند. پاره ای از زبان های ایرانی دوره نو را می توان دنباله یکی از زبان های ثبت شده دوره میانه دانست. برای نمونه، زبان فارسی دنباله فارسی میانه است و یغنابی دنباله سغدی است. پرسش این است که آیا می توان گویشی ایرانی در دوره نو را دنباله پهلوی اشکانی دانست؟ این پژوهش بر آن است تا با بررسی نوشته های برجای مانده از فرقه حروفیه که در کتاب واژه نامه گرگانی صادق کیا (Kya, 2012) آمده است، پیوندهای زبانی میان پهلوی اشکانی و گویش گرگانی را از دید واژگانی، واجی و نحوی روشن نماید. برای این کار، واژه ها و جمله هایی از پهلوی اشکانی تورفانی و کتیبه ای برگزیده شده و با واژه ها و جمله هایی از گویش گرگانی در نوشته های فرقه حروفیه سنجیده شده است. در پایان، این نتیجه به دست آمد که گویش گرگانی یکی از بازمانده های زبان ایرانی پهلوی اشکانی بوده که تا دوره تیموری یا پس از آن در گرگان رواج داشته و سپس رو به خاموشی رفته است.

کلیدواژگان: پهلوی اشکانی، زبانهای ایرانی، گویش گرگانی، فرقة حروفیه، زبانشناسی تاریخی -

صفحات 131-150

پژوهش حاضر، با استفاده از روش پتانسیل های وابسته به رویداد (ای.آر.پی)، به بررسی چگونگی پردازش زبان لفظی و استعاری در زبان فارسی و نقش نگاشت مفهومی در فرایند این پردازش پرداخته است. پیش بینی نگارندگان این است که درک جمله های لفظی و جمله های استعاری متعارف همزمان روی می دهد. درک جمله های استعاری بدیع نسبت به جمله های استعاری متعارف کندتر انجام می گیرد. همچنین، پیش بینی شد، نگاشت مفهومی در استعاره های متعارف و استعاره های بدیع به شیوه ای متفاوت روی می دهد. چهارصد جمله لفظی، استعاری متعارف، استعاری بدیع و بی معنی (هر وضعیت صد جمله) با استفاده از نرم افزار سایکوپای طراحی شد و روی صفحه رایانه نمایش داده شد. امواج مغزی 22 آزمودنی به هنگام خواندن این جمله ها، با استفاده از دستگاه ثبت ای. ای. جی ثبت گردید. اطلاعات مربوط به دامنه میانگین مولفه N400، با استفاده از نرم افزارهای ای. ای. جی لب و ای. آر. پی لب استخراج شد. داده ها، با استفاده از روش اندازه گیری تکراری (آنوا) و مقایسه دوسویه در نرم افزار اس.پی.اس.اس تحلیل گردید. یافته های مربوط به روش پتانسیل وابسته به رویداد نشان داد که جمله های لفظی و استعاری متعارفپردازش یکسانی دارند. استعاره های متعارف سریع تراز استعاره های بدیع پردازش می شوند. نگاشت مفهومی در درک استعاره های بدیع به وسیله فرایند قیاس روی می دهد، اما در درک استعاره های متعارف از طریق فرایند مقوله بندی روی می دهد.

کلیدواژگان: پردازش زبان مجازی، استعاره مفهومی، استعاره متعارف، استعاره بدیع، روش پتانسیل وابسته به رویداد، مولفه N400 -

صفحات 151-175کاربردشناسی، یکی از گرایش های نسبتا نوظهور در رشته زبانشناسی است که همواره مورد توجه پژوهشگران بوده و به حوزه مستقل از پژوهش های زبانشناختی تبدیل شدهاست. با توجه به اهمیت دانش کاربردشناسی در بهبود توانش ارتباطی زبانآموزان، پژوهش حاضر به بررسی تاثیر آموزش تلویحی و تشریحی با استفاده از برشهای ویدیویی بر درک کاربردشناسی دو کنش گفتاری معذرت خواهی و امتناع پرداختهاست. به این منظور، تعداد 49 دانشجوی نیمسال اول رشته ادبیات و آموزش زبان انگلیسی سطح متوسط از دانشگاه گلستان برمبنای آزمون تعیین سطح آکسفورد به عنوان جمعیت نمونه انتخاب شدند. محدوده سنی این زبان آموزان، بین 18 الی 33 سال بود. زبان آموزان به صورت تصادفی در سه گروه آموزش تلویحی، آموزش تشریحی و کنترل گروه بندی شدند. در گروه تشریحی، زبان آموزان توضیحات فراکاربردشناسی، بازخوردهای مستقیم وآموزش های مستقیم ارتقاءآگاهی دریافت کردند. هر چند زبان آموزان گروه تلویحی تحت آموزش ضمنی قرارگرفتند. در آموزش گروه تلویحی و تشریحی از 60 فیلم کوتاه استفاده شد که از سریال «فرار از زندان» و مجموعه فیلمکتاب «تاچ استون 2» برگرفته شده بودند. در مقابل، گروه کنترل هیچ گونه آموزشی برای یادگیری چگونگی استفاده از کنش های گفتاری معذرت خواهی و امتناع دریافت نکردند و بخش های گوناگون کتاب «تاچستون 2» آموزش داده شد. پیش و پس از دوره 10 جلسه آموزش، هر سه گروه در آزمون تکمیل کلام چندگزینه ای شرکت کردند. یافتههای بهدستآمده از آزمون تحلیل واریانس یک متغیره نشان داد که درک زبان آموزان از کنش گفتاری معذرت خواهی و امتناع در گروه آموزش تلویحی و تشریحی، پس از اجرای آموزش ارتقاء و پیشرفت داشتهاست. همچنین، یافتههای آزمون شفه نشان داد عملکرد گروه آموزش تشریحی بهتر از گروه تلویحی بوده و همچنین عملکرد گروه آموزش تلویحی بهتر از گروه کنترل بودهاست. بر پایه نتایج این پژوهش به آموزگاران زبان انگلیسی پیشنهاد می شود که با استفاده از برش های ویدیویی راهکارهای آموزش تشریحی را بیش از آموزش تلویحی مورد توجه قرار دهند.کلیدواژگان: کاربردشناسی، آموزش تلویحی، آموزش تشریحی، معذرتخواهی، امتناع

-

صفحات 177-204

براهویی، زبانی غیر ایرانی و از شاخه شمالی خانواده زبان های دراویدی است که محل اصلی رواج آن، کشور پاکستان است اما در ایران نیز گویشورانی دارد. امروزه اغلب گویشوران براهویی در ایران در منطقه سیستان و بلوچستان زندگی می کنند اما گروهی اقلیت با جمعیت کمتر از هزار نفر در جنوب کرمان زندگی می کنند. بخشی از این گروه اقلیت، در روستای تم میری شهرستان رودبار جنوب ساکن اند و علاوه بر براهویی، به زبان فارسی و نیز گویش رودباری که گویش مسلط منطقه است، سخن می گویند. دو قرن مجاورت و هم زیستی با بومیان اصلی منطقه و استفاده از گویش رودباری برای تعامل با آن ها، سبب به وجود آمدن گونه ای جدید از زبان براهویی شده است که می توان آن را گونه براهویی رودبار جنوب نامید. منطقه مورد پژوهش، روستای تم میری شهرستان رودبار جنوب است. تمام داده های این پژوهش، به شیوه میدانی و به وسیله مصاحبه با گویشوران مرد و زن (30 نفر)، از سطح های مختلف سنی (از 9 تا 100 سال) و تحصیلی (از بی سواد تا تحصیل کرده) گردآوری شده است. هدف پژوهش حاضر، توصیف و بررسی ساختمان فعل در این گونه زبانی است. فعل در این گونه به دو شکل ساخته می شود؛ در برخی افعال، فعل بر پایه یک ماده ساخته می شود. به بیان دیگر، ماده فقط بر عمل دلالت می کند. در برخی دیگر، فعل بر پایه دو ماده ماضی و مضارع ساخته می شود. وجه های این گونه زبانی، اخباری، التزامی و امر هستند. و زمان های براهویی، مضارع اخباری، مضارع التزامی، مضارع مستمر، آینده، امر، ماضی ساده، ماضی استمراری، ماضی مستمر، ماضی نقلی و ماضی بعید هستند.

کلیدواژگان: ساختمان فعل، گونۀ زبانی براهویی رودبار، خانوادۀ زبانهای دراویدی، رودبار جنوب -

صفحات 205-240

این پژوهش، با روشی مقابله ای و انتقادی بر آن است تا به واکاوی ایدیولوژی پنهان قدرت، در لایه های گفتمانی متن حاصل از دو قانون اساسی مرتبط با «حقوق ملت» بپردازد. این دو قانون مشتمل بر قانون جمهوری اسلامی (1358هجری شمسی، 1979 میلادی) و قانون اساسی مشروطه (1285 هجری شمسی، 1906 میلادی) هستند. به این منظور، 17 سازه استدلالی-گفتمانی (گزینش واژه ها و تعبیرات خاص از طریق نام دهی)با استناد به آرای انتقادی فرکلاف (Fairclough, 2015)، ون لیون (Van Leeuwen, 2008) و مشخصه های بافت محور هایمز (Hymes, 1974) در دو متن حقوقی، تفسیر و تبیین گردیدند. در این پژوهش،مولفه های معنا جامعه شناختی مستخرج از دو متن قانون اساسی و مشروطه از طریق اعمال فرمول مجذور خی از جنبه کمی مورد بررسی قرار گرفت. نتیجه این بررسی نشان داد که در میزان بهره گیری از مولفه های طرد، جذب و زیرشمول های آن ها در بازنمایی ایدیولوژی پنهان قدرت بین دو قانون اساسی، تفاوت معناداری وجود دارد. همچنین، بر پایه تحلیل کیفی بین صورت بندی های ایدیولوژیک و طبیعی شدگی مناسبات قدرت، از طریق لایه های صوری زبان، ارتباطی دوسویه برقرار است. بنابراین، در فرایند تحلیل انتقادی این دو متن، به واسطه ساخت ایدیولوژیک استنتاج شده از دو متن حقوقی، میزان آگاهی بخشی، قدرت دهیو روابط نابرابر قدرت،از طریق بازنمایی سازه های استدلالی-گفتمانی، به دست می آید.

کلیدواژگان: سازههای استدلالی-گفتمانی، تحلیل گفتمان انتقادی- حقوقی، صورتبندیهای ایدئولوژیک قدرت -

صفحات 241-265

تفکر نقاد و خودمختاری فراگیران، ازجمله موضوعاتی است که بسیار در پیشینه پژوهش های آموزش زبان انگلیسی مورد بحث و بررسی قرار گرفته است. در این راستا، برای پی بردن به کارآمدی بیشتر این دو مقوله در زبان آموزی، مطالعه حاضر به مقایسه تاثیر آموزش تکنیک های تفکر نقاد با تکنیک های خود مختاری در پیشرفت مهارت گفتار زبان آموزان انگلیسی پرداخت. به این منظور، 90 نفر زبان آموز سطح متوسط کلاس های یکی از آموزشگاه های آزاد زبان در تهران که پژوهشگران این مطالعه به آن ها دسترسی داشتند، در یک نمونه آزمون اولیه انگلیسی (پت) شرکت کردند. در نتیجه، 64 نفری که نمره های آن ها در محدوده یک انحراف معیار بالا و پایین میانگین نمره های کلی آن 90 نفر قرارگرفته، انتخاب شدند. لازم به اشاره است که این آزمون پیش از این، میان 30 زبان آموز دیگر در همان آموزشگاه پیش آزمون شده بود. در مرحله بعد، آن 64 نفر به صورت تصادفی به دو گروه آزمایشی گروه بندی شدند تا یک گروه تحت آموزش تکنیک های تفکر نقاد و گروه دیگر تحت آموزش تکنیک های خودمختاری به عنوان دو روش آموزشی مختلف قرار گیرند. پیش از آغاز آموزش نیز مهارت گفتاری هر دو گروه با استفاده از پیش آزمون گفتار مورد سنجش قرار گرفته بود و تفاوت معناداری بین میانگین نمرات آن ها مشاهده نشد. در انتهای دوره آموزشی 14 جلسه ای، دو گروه در پس آزمون یکسان گفتار شرکت کردند. نتیجه تحلیل آماری مربوطه (آزمون نمونه های مستقل تی) نشان دهنده آن بود که آموزش تفکر نقاد، تاثیربرتری بر مهارت گفتار نسبت به آموزش خودمختاری دارد. یافته های مورد اشاره، بیش از پیش برتری آموزش تفکر نقاد در کلاس های زبان را نسبت به سایر روش های تدریس نشان می دهد و بر ضرورت توجه بیشتر به این سبک آموزش تاکید می کند.

کلیدواژگان: آموزش زبان انگلیسی، مهارت گفتار، تفکر نقاد، خودمختاری -

صفحات 267-295

تحلیل گفتمان انتقادی، پیوند میان زبان، قدرت و ایدیولوژی را به وسیله کشف ساختارها یا مولفه های گفتمان مدار نمایان می سازد. پژوهش حاضر، با هدف کشف لایه های پنهانی معانی تمبرهای پیش و پس از انقلاب در چارچوب تحلیل گفتمان انتقادی به انجام رسیده است. تحلیل گر این پژوهش با بررسی متن های تصویری نوشتاری می کوشد تا دریابد چگونه تمبرها زبان را به عنوان فرهنگ بدیهی، طبیعی و اجتناب ناپذیر به تصویر می کشند و کارکردهای متفاوت گفتمانی، اجتماعی و فرهنگی آن ها را بررسی می نماید. بنابراین 78 نمونه (39 تمبر پیش از انقلاب و 39 تمبر پس از انقلاب) از تمبرهای دهه 50 (1360-1350ه.ش) با بهره گیری از مولفه های جامعه شناختی-معنایی الگوی ون لیوون به صورت کیفی و کمی تجزیه تحلیل شدند. تجزیه و تحلیل داده ها نشان داد که ایدیولوژی حاکم بر اذهان طراحان، صاحبان اندیشه و حاکمان هر دو دوره با بهره گیری از مولفه های گفتمان مدار همچون تشخص بخشی، فردارجاعی، مکان مداری، ابزارمداری، منفعل سازی، کمرنگ سازی، پنهان سازی و موارد مشابه در متون بازنمایی می شوند. با این وجود، تجزیه و تحلیل داده های آماری هم درستی این یافته ها را تایید کردند. همچنین مولفه های گفتمان مدار با ایدیولوژی و روابط قدرت در تعامل تنگاتنگ هستند و رابطه دوسویه با هم دارند که با بررسی این ساخت ها در متن ها و نهادهای اجتماعی قابل تبیین است.

کلیدواژگان: تحلیل گفتمان انتقادی، قدرت، ایدئولوژی، مؤلفههای جامعهشناختی- معنایی(Van Leeuwen، 2008) -

صفحات 297-318

بسیاری از آثار موجود در حوزه واج و آواشناسی، ساخت هجای زبان فارسی را به صورت CV (C (C)) در نظر گرفته اند. در نظر گرفتن چنین ساختی برای زبان فارسی، به این معناست که اولا در زبان فارسی هیچ هجایی با واکه آغاز نمی شود و دوما در زبان فارسی توالی واکه ها امکان پذیر نیست. این جستار، با هدف بررسی امکان التقای واکه ای در گفتار محاوره ای، سریع و پیوسته و همچنین واکاوی تاثیر عناصر صرفی (به طور خاص واژه بست ها) بر میزان و چگونگی بروز التقای واکه ای انجام شد. به این منظور، 1500 داده گفتاری که دربرگیرنده (5 واکه (1)* 6واکه (2)* 5 محیط [4 محیط پی بستی + e معرفه]* 10 گویشور) بودند، ضبط شدند. سپس این داده ها، با استفاده از نرم افزار پرات ویرایش 19. 0. 6 مورد تجزیه و تحلیل صوت شناختی قرار گرفتند. نگارندگان با تکیه بر یافته های بهدست آمده از تحلیل های صوت شناختی پی بست های واکه ای بر این باورند که از نظر آوایی می توان الگوی VC را نیز برای ساخت هجایی زبان فارسی مفروض دانست. همچنین در مواردی که با التقای واکه ها روبه رو هستیم، در 73/55 درصد موارد هیچ گونه همخوان میانجی ای میان دو واکه درج نشده است. در 27/44 درصد موارد نوع همخوان میانجی درج شده وابسته به شرایط آوایی و صرفی واژه میزبان و پی بست اضافه شده به آن واژه است. علاوه بر این، میزان درج همخوان میانجی در دو پی بست واکه ای o (عطف) و o (کوتاه شده را) که تلفظ یکسانی دارند، نمایانگر تاثیر شرایط صرفی و واجی پی بست های واکه ای بر نوع و میزان رخداد التقای واکه ای است.

کلیدواژگان: پیبستهای واکهای، التقای واکهای، هجابندی، زبان فارسی گفتاری، عناصر صرفی

-

Pages 7-34

Nominalized words are complex nominals, which have their own particular derivational structure. These nominals can be derived from different parts of speech. Correspondingly, a deadjectival nominal is a nominal that is derived from an adjective; Although deadjectival nominals and nominalization, in general, have been cases of the most important issues of syntax and morphology in theoretical linguistics, less attention has been paid in the literature to deadjectival nominals (Roy, 2010; Alexiadou & Martin, 2012; Borer, 2013; Arch & Marin, 2015). On the other hand, a large number of works on nominalizations is concerned with deverbal nominals (Chomsky 1970; Grimshaw 1990; Picallo 1991; Marantz 1997; Alexiadou 2001; Borer 2013, among many others).With reference to Persian deadjectival nominals no attention has been paid to these nominals; therefore, the present study is an attempt to provide a descriptive syntactic analysis of Persian deadjectival nominals based on the Exoskeletal framework as developed in Borer (2013). Borer’s (2013) theoretical framework gives a complete account of nominalization with a detailed syntactic explanation of the underlying syntactic structure of deadjectival nominals; consequently, this approach is opted as the theoretical framework of the present study due to the following reasons: first, the model in which all word formation takes place in syntax is premier to the models sticking to a supreme lexicon; second, since all categories are syntactic and functional, the redundancy between lexical and functional categories is omitted. Borer (2005, 2013) hypothesizes that words do not have any specific lexical category and their exact category is dependent on their syntactic context they occur. Regarding nominalization process, Borer (2013) argues that derivational suffixes merge with their roots in the syntax rather than morphology, that is to say, there is a particular syntactic mechanism that underlies the formation of nominals. Also, she, following Roy (2010), divides deadjectival nominals into two groups: Stative deadjectival nominals and Quality deadjectival nominals. She claims both types of deadjectival nominals have argument structure. However, Stative deadjectival nominals have different syntactic structure from Quality deadjectival nominals. Borer (2013) asserts, although Stative deadjectival nominals contain complete predicative structure with overt external argument and Degree phrase[1], Quality deadjectival nominals never have a complete predicative structure; also, the external argument in these nominals are covert (pro) and the occurrence of Degree phrase in their structure is not necessary. As aforementioned, in the present study, we try to analyze the underlying syntactic structure of Persian deadjectival nominals adopting Borer’s (2013) Exoskeletal framework. The range of data under analysis is restricted to a single language i.e., Persian. The data were taken from Derivational suffixes in Modern Persian (Kashani, 1992), The Derivational Structure of Word in Modern Persian (Kalbassi, 2008) and Dictionary of prefixes and suffixes in Persian (Farshidvard, 2007). It is worth noting that Persian deadjectival nominals are characterized by the presence of derivational suffixes. The categorial suffixes in Persian deadjectival nominals are: /-ӕk/ in /zӕrd-ӕk/ ‘carrot’; /-ɑ/ in/rowʃӕn-ɑ/ ‘light’; /-eʃ/ in /nӕrm-eʃ/ ‘leniency’; /-kɑr/ in /sefid-kɑr/ ‘coppersmith’;/-gӕri/ in /vӕhʃi-gӕri/ ‘brutality’; /-nɑ/ in /tӕng-nɑ/ ‘restriction’; /-e/ in /zӕrd-e/ ‘yolk’; /-jӕt/ in /hӕsɑsi-jӕt/; ‘allergy’; /-i/ in /ʧɑq-i/ ‘obesity’ (all data were taken from Kashani (1992/1993), Farshidvard (2007) and Kalbassi (2008)). The results of the present study show that the structures of Persian suffixal deadjectival nominals are coincident with Borer’s Exoskeletal framework (i.e Persian has both Stative deadjectival nominals and Quantity deadjectival nominals). The deadjectival nominal /vӕhʃi-gӕri/ ‘brutality’ is an instance of Persian Stative deadjectival nominals which can appear in /vӕhʃigӕri-e ӕli/ ‘Ali’s brutality’, in the derivation of which CN[A][2] needs to scope over the predicate structure that entails Degree phrase. In other words, the Stative deadjectival nominal /vӕhʃi-gӕri/ is derived from merging the derivational suffix /-gӕri/ with the extended projection of the adjective. In the structure of this Stative deadjectival nominal, first the adjective /vӕhʃi/ moves to Degree phrase to achieve its predicative case. Then it moves to become the complement of the extended projection of the adjective CN [A] to merge with the categorial suffix /-gӕri/; at this point, the derivation of the Stative deadjectival nominal /vӕhʃi-gӕri/ will be completed. Also in the derivation of this structure, the determiner phrase /ӕli/ which is in the specifier of Stative phrase raises to the extended projection of nominal(EXSN) to get the genitive case. In Persian the realization of genitive marker (ezafe) is post-nominal. On the other hand, in the Persian Quality-deadjectival nominals like/ʧɑqi/ ‘obesity’ which is obtained from /?ӕli-j-e ʧɑq/ ‘obese of Ali’ the adjective / ʧɑq / moves to the extended projection of nominal [EXSN] then it raises to state phrase to achieve its predicative case. Then it moves to become the complement of the extended projection of the adjective CN [A] to merge with the categorial suffix /-i/. At this point, the derivation of the Quality deadjectival nominal /ʧɑqi / will be completed. Similarly, in the derivation of this structure, the external argument pro which places in the specifier of Stative phrase raises to the extended projection of nominal(EXSN) to get the genitive case. It is worth mentioning that Quality deadjectival nominals (e.g. /mӕhdud-i-jӕt/ ‘restriction’), have Stative deadjectival nominal counterparts which have complete predicative structure with an overt external argument. In addition, Quality deadjectival nominals denote the mass abstract entities. Moreover, the research results indicate, although Borer(2013) didn’t introduced Result deadjectival nominals in her model, Persian has a kind of Result deadjectival nominals which does not have an argument structure. Result deadjectival nominals, (like: /sӕbz-e/ ‘grass’) only have the attributive structure and represent the count concrete entities. [1] Borer (2013) believes that presence of Degree phrase is necessary in the derivation of Stative deadjectival nominals [2] C-functor which projects the nominal and takes adjective

Keywords: Exoskeletal approach, nominalization, deadjectival nominals, stative deadjectival nominals, quality deadjectival nominals -

Pages 35-54

Human communities with different languages, because of business transactions, cultural and religious relationships and even war, have always been in close contact with each other. One of the consequences of these relationships is transmitting the language elements and structures from one language to another. This phenomenon is generally called “borrowing”. Borrowing occurs in all levels of language ranging from orthography to phonetics, phonology, morphology and syntactic structures, but the most frequent type of borrowing is lexical borrowing or borrowing the whole word (Arlotto, 2005). One of the important facts of borrowing is that through this process, borrowed words conform to the grammatical rules of the borrowing language. This phenomenon is called “nativization”. Since, nativization in any language occurs on the basis of the specific grammatical rules of that language, it gets a title related to the name of that language; for instance, nativization in German is called “Germanization (Eindeutschung)” (Lane, 2012, p. 8), or in Arabic is entitled “Arabicization (التعریب)”, (Khadim, 2012, p.16); therefore, it is proposed to name this process in Persian language as “Persianization”. One of the manifestations of nativization is “reanalysis”, the primary cause of which is illiteracy, ignorance and unacquaintance of native speakers with the etymology of borrowed words. In reanalysis, a part of a borrowed word, because of formal similarity, is mistaken for a native word or morpheme and is substituted by that native word or morpheme. The works conducted so far on nativization, either have not paid any attention to reanalysis, or just mentioned some instances of this phenomenon without giving any structural analysis or classification of it. Therefore, in this paper, attempts are made to investigate the structure of reanalysis and to classify it according to its structure. The data of the study have been collected in informal situations from the colloquial communications of low-educated old people or illiterate young children who are not familiar with the original or written forms of borrowed words. Because of the rising educational level of common people and their excessive contact with written media and the messengers of cyber space, the frequency of the data is dramatically decreasing. In all the cases of reanalysis, three common elements can be found. These elements include: borrowed word, native word, and the relevant semantic feature of borrowed word. The relevant semantic feature of the borrowed word can be the function, the formal shape or the meaning of the borrowed word. There exist also three relationships among these elements: The first one is the conventional relationship between the borrowed word and its semantic feature which is a signifier and signified relationship. The second one is the accidental relationship between the borrowed word and the native word which is the result of accident and a formal similarity relationship. The third one, is the relationship between the native word and the semantic feature of the borrowed word which is an indicative relationship. To occur an instance of reanalysis, all of the above mentioned factors and relationships must be met and the absence of one of them, prevents its occurrence. As it is revealed, the indicative relationship between the semantic feature of borrowed word and native word can vary according to form, function and meaning of the borrowed word. With respect to these variables, reanalysis can be classified into formal reanalysis, functional reanalysis and semantic reanalysis. In the following, each of these types of reanalysis is further explained with an example. Formal Reanalysis occurs on the basis of the formal shape of the object that the borrowed word denotes it. For example, the borrowed word “hamburger” has been reanalyzed as “hamburger”. It has occurred on the basis of the indicative relationship between the round shape of the object that the word “hamburger” denotes it and the meaning of native word “gerd” with the meaning “round”. Therefore, “hamburger” has been reanalyzed to “hamburger”. In Functional Reanalysis, the function of the borrowed word and its accidental similarity with the native word play the main role in forming the functional reanalysis. For instance, the borrowed word “address” which refers to the details of the place someone lives and the function of which is to help somebody else to reach there, has been reanalyzed to “address”. The reason is that the final syllable of the borrowed word (-ress) is similar to the native word “ras” with the meaning “to arrive” or “to reach”. Therefore, the final syllable “-ress” has been replaced by “ras”; and the borrowed word “address” has been reanalyzed as “addras”. In Semantic Reanalysis, there is no formal or functional relationship, rather, there exists an indicative relationship between the meaning of the borrowed word and the native word, therefore the native word replaces the whole borrowed word or part of it. For example, the borrowed word “double” means something that is twice as big as something else. The part “dou-” is also accidentally similar to the Persian native word “do” which means “two”. Because of the indicative relationship between the meaning of “double” with the native word “do” on the one hand, and the accidental similarity between the part “dou-” and the native word “do” on the other, the native word “do” has replaced the part “dou-”. This construction has been further reanalyzed by substituting the native word “do” with another native word “se” with the meaning “three” and producing the colloquial word “suble” which means “something that is thrice as big as something else”.

Keywords: Borrowing, Persianization, lexical reanalysis, Borrowed word, Native word -

Pages 55-82

Given their diverse cultural backgrounds, language learners should possess an appropriate level of cultural intelligence to learn Persian as a second language. In recent years, various students from different cultural backgrounds have joined the education system of Iran, most of whom are non-native Persian speakers with little previous exposure to the Persian language. In such a situation, owing to the lack of intercultural adaptation, individuals may experience culture shock. Culture shock is the type of experience that second language learners might face while learning a language in a different context. Therefore, learning the target culture in second language learning classes turns into a crucial concern. Cultural intelligence which is nowadays a buzzword refers to individuals' sensitivity and adaptability to cultural issues, contributing to more intercultural understanding. Cultural intelligence, which manifests itself in intercultural communcations, is a form of communicitve competence that highlights effective interpersonal interactions in culture-bound situations. According to Earley and Ang (2003), cultural intelligence corresponds to the individuals’ successful compatibility with the cultural environments which are different from those of their own. Students’ cultural intelligence can help them understand the target language norms and values and have more effective communication with their teachers. Owing to the importance of this new form of intelligence and its potential role in the enrichment of Persian teaching methods, the current study intends to introduce and thereafter implement the emotioncy-based language instruction (EBLI) model, constituting avolvement (null), exvolvement (auditory, visual, and kinesthetic) and involvement (inner and arch). Emotioncy, which is a blend of emotion and frequency of the exposure to different senses, was first introduced by Pishghadam, Tabatabeeyan, and Navari (2013, p. 149). The concept is based on developmental, individual differences, relationship-based (DIR) model that takes emotions as the basis of learning. According to the emotioncy model, the vocabularies of a given language have different emotional levels for different people, and the higher the level of emotioncy for a word is, the easier it is to be learned. Emotioncy consists of different types and kinds including avolvement (null), exvolvement (auditory, visual, and kinesthetic), and involvement (inner and arch). In this categorization, null refers the person with no previous experience of a given item/concept. At the auditory level, the person is supposed to have heard some points about the given word. At the visual level, the person has not only heard about the concept but has seen it as well. The next level is the kinesthetic, at which the person touches the item in addition to involving the senses mentioned above. At the inner level, the person directly experiences the item and at the final level, namely arch, the person reaches the highest level of knowledge about the concept by conducting research on it. It should be also mentioned that emotioncy levels are hierarchical. To evaluate the extent to which this model contributes to the build-up of the Persian language learners’ cultural intelligence, the emotioncy and cultural intelligence scales were used to collect data from 60 non-Persian female students coming from 16 different nationalities. The participants were categorized into four groups and were instructed based on the varieties of the EBLI in a total of 22 sessions during 6 weeks. Four cultural issues addressing different dimensions of the Iranian culture were selected in a way to be unfamiliar to the participants. To check the level of familiarity, the participants were asked to take a scale containing 12 culture-related issues and concepts to guarantee that they had zero knowledge of them. To make the comparisons more logical, the researchers tried to teach all cultural issues and concepts to all groups of participants in a way that everybody could experience all types of emotioncy levels (null, auditory, visual, kinesthetic, inner, and arch). The instructor’s overall evaluation of the learners revealed that the EBLI could significantly boost the non-Persian language learners’ level of cultural intelligence. It was further concluded that those language learners with higher levels of cultural intelligence see classes as a place where they can improve their linguistic competence, have better ideas and stronger relations, and communicate more effectively with their teachers and classmates. They, therefore, can openly express their feelings, easily accept others, and speed up their own language learning process. Consequently, The EBLI is suggested to be applied in Persian language teaching classes. In the end, it is our belief that this new perspective which places more emphasis on the interface of sense and emotion can open up new horizons for second language teachers to do more research into it, contributing to language learning processes.

Keywords: Persian learning, emotioncy, Cultural Intelligence, Emotion, senses -

Pages 83-109Arabic language is among Semitic languages and because of being the religion language has a huge number of speakers. English language is among Indo-Europeans and it is science and technology language; furthermore, for being spoken globally, it has a significant status. In new theories, Halliday’s grammar is compiled with functional objectives. Clause is the main unit in Halliday’s grammar and each utterance which is concentrated around a verbal group is a clause. He has studied ideational, intersectional and textual meta-functions in his grammar. Textual meta-function is represented in theme and rhyme, intersectional meta-functions in the relation between speaker and addressee, and ideational meta-function in transitivity and processes. In his systematic grammar and transitivity structure, the process is the origin of every event and is represented by ideational meta-function. In Ideational meta-function, language arranges person experience. Empirical processes are the core and the center of a clause. A clause has participant and other circumstantial elements which have an effect on the amount of transitivity. Holliday’s functional grammar has paid vital attention to the meaning. Based on the assumption that experience patterns are DE codified in processes and transitivity, he has posed sextet processes. The main process is subdivided to material, mental and relational. Secondary process is divided to verbal, behavioral and existential. Main Participants of these processes are named differently such as actor in material, sensor in mental carrier in relational, sayer in verbal, behaver in behavioral and existent in existential. This inquiry studies comparative processes in the Arabic and English languages and tries to express differences and similarities in processes, main participants and circumstantial elements. It makes an effort to answer these questions: what is the definition of processes and verbs, transitivity in two languages, differences and similarities in process type. Structuralism believes that all verbs are transitive or intransitive and in the transitive verb, the action extents from verb to subject and object, but in functional grammar as Halliday and Mattsin have expressed: the more participants and circumstantial elements, the more is transitivity. The study of traditional grammar and modern linguistic in two languages shows that dissension in transitivity is in terminology and naming and in Arabic and English languages, it is used in the same meaning, but in the Arabic language in addition to being in context, there are some special forms making the verb transitive or intransitive, e.g. adding some prefixes, doubling a letter, etc. can make a verb transitive or vice versa that is very important. In Arabic language, transitivity is for verb and those verbs are called transitive verbs, but in practice whole clause is involved in belonging to verb, as in the English language it is extended to the whole clause and the clause is transitive or intransitive. Unlike Arabic language, there are no processes in the English that have three objects leading to more transitivity and the first object and second are direct and indirect, respectively. There is no category like those of Halliday in the Arabic language. Only Mental processes in Arabic are separated from others based on having two or three objects and they have been named (qolob) which means some thing related to heart, but in taking a clause as a phenomenon both languages are the same. Crucial differences are in relational and verbal processes. In English, there is a relational process which is mentioned in the clause and is like other processes, but it does not exist in Arabic language. The theme and rhyme can clarify the meaning of the clause, as Halliday and Matssin have described clearly in their book: “Introduction to functional grammar”. In some cases, there is a relational process with different names. In Arabic, verbal processes are deleted and substituted by interjections. About existential process, both languages are different. In English language, the word (there) fills the subject place but originally it is not a subject. In Arabic, we have existential verb with subject like other processes and even some relational verbs can be used as existential when they are complete. It means they do not need another participant to completed. Some terminologies in functional grammar have different expressions in Arabic, e.g. attribute in material processes is (Hall) in Arabic language, so circumstantial elements in both languages, despite different expressions, have their effects on clause and consequently, on transitivity.Keywords: English language, Arabic language, functional grammar, transitivity process

-

Pages 111-130

The term Iranian language is used for any language which is descended from proto-Iranian language, spoken in central Asia. Iranian languages have been spoken in the areas from Chinese Turkistan to the Western Europe. This language (proto-Iranian) comes from proto Indo-Aryan. The Iranian and Indo-Iranian (Aryan) languages belong to the main language called proto-Indo European language. This language perhaps was spoken in the area of southern Russia. The Iranian languages have three chronological periods: Old, Middle and New Iranian languages. Persian is the only language which has document in three stages. The Iranian languages in old Iranian stage are Median, Persian, Saka and Avesta which have corpus or words in corpus languages. The Iranian languages in Middle stage are Persian, Parthian, Sodian, Bactria, Chorosmian, and Saka languages from which the Parthian belongs to the north west Iranian languages. The Parthian languages have evidences in Middle stage and New stage of Iranian languages. This language has also evidences in Parthian period and Sassanian period. The Parthian evidences are also from Manichaean literature. The Manichaean literature belongs to Manichaean Religion. It is from Arsakid and Sassanian period and also from Islamic period. The known Middle Iranian language spoken from about 3 centuries include: Khotanese, Sogdian, Chorasanian, and in Bactria Bactrian was spoken. In Parthia, Parthian was spoken as the language of Arsacids. In pars of pre-Sasanian dynasty, Middle Persian, called Pahlavi was spoken. This language became the official language of Sassanian dynasty. It was the language of Zoroastrian literature called Pahlavi. Today the Iranian language is spoken in Turkey, Iran, Caucasus, in the west of Chinese Turkestan and Pakistan, Afganistan and Tajikistan. These languages are Ossetic spoken in Ossetia: Digoroa and Iron. Kurdish spoken in three variants in eastern Turkey and Syria, northern Iraq and west Iran, Baluchi, spoken in eastern Iran and western Pakistan and in southern Afghanistan and central Asia and Pashto spoken in Afghanistan and Pakistan. These languages and dialects can be divided in to several larger groups on the basis of grammatical, phonetic and lexical isoglosses. The languages of southeastern and southern Iran often have a/d/ where other Iranian languages have /z/ (for example, dân, Farsi to know, but zân in Kurdish). Other asoglosses, for example the word for “to do” kar/Kard (Kird) and kun/kurd (kird), gōw-goft in farsi and wāč- (wāj-/wāxt) in west Iranian dialects (Kurdi, Gruganni, Taleši and so on). The start of Parthian period may be placed after the middle of the 3rd century BCE. When the conflict between Seleucus II and his brother Antiochus Hierax opened the way for the eruption of the nomadic Iranian Parthians in to the province of Parthian in north west of Iran also the (Selucid dynasty). After that, they become known as Parthian and they used the Middle Iranian language of north west of Iran (Parthian language). The subsequent establishment of the Parthian empire took place in two stages: Mithradatse I (ca 171-139 BCE) and Mithradates II (ca 124-88 BCE). In this time the territorial expansion completed. As said, Parthian in one the Iranian language the text of which has remained in the middle period of Iranian languages from the Parthians and followers of Manichaean religion. There is no trace of this language in the modern period of Iranian languages. Nevertheless, the New Iranian dialects each follow one of the Iranian languages in the middle and ancient period. Some of new Iranian languages can be considered the sequel of the Middle period languages. For instance, the Persian language is classified a continuation of Middle Persian and the Yaghani is a continuation of Sogdian. The question is, can an Iranian dialect in the new era be considered as a continuation of Parthian language? The study aims to clarify the linguistic links between the Parthian and Gorgâni dialect from the verbal, phonological, and syntactic point of view, by examining the literary works of Hurufiyye sect, written in Sadegh Kia’s Gorgâni Dictionary. To this end, words and sentences have been selected from the Turfan and inscriptional Parthian, and have been compared with the words and sentences of the Gorgâni dialect in the Hurufiyye works. The Hurufiyye works belong to an Islamic sect, which believe in the meaning of the words. This sect had written these works in new Persian, but with elements from Gurgâni dialect. In the end, the result shows that Gurgâni dialect, in the investigated evidence, can have links with one of the survivors of the Middle Iranian language, the Parthian. This dialect has been prevalent in Gurgâni since the Teymurid era or later, and then has gone into silence.

Keywords: Parthian, Iranian languages, Gurgâni literary works, Hurufiyye sect, historical linguistics -

Pages 131-150

There are three primary models to deal with literal/non-literal language processing. The first is the indirect access model proposed by Grice (1975) and Searle (1979). As indicated by this model, sentences are first processed literally when the literal meaning was not the adequate interpretation; at that point the look for the metaphorical interpretation begins. The second is the direct access model proposed by Glucksberg et al. (1982). As indicated by this model, metaphors are processed as easily as literal sentences. Their findings demonstrated that there is no contrast between the processing of literal sentences and metaphor. The third is a continual processing model, for example, “The contemporary theory of metaphor”, Lakoff (1993); “the Gradient Salience Model”, Giora (1997, 2003) and “the Career of Metaphor Model”, Bowdel and Gentner (2005). In these models, literal sentences and conventional metaphors are processed in the same way. Lakoff (1993) believes that the meaning of literal sentences and conventional metaphors are accessed at the same time since they both are retrieved from memory. But Giora (1997, 2003) believes that the reason for this simultaneous processing is that conventional metaphors are as salient as literal sentences. Novel metaphors are processed more slowly than literal sentences and conventional metaphors. Their processing includes more cognitive efforts. Lakoff (1993) asserts that this slower processing of novel metaphors is due to the comparison and the conceptual mapping of the source domain on the target domain (online processing compared with retrieving from memory). Bowdel and Gentner (2005) believe that novel metaphors are processed as “analogy”, but conventional metaphors are processed as “categorization”. However, Giora (1997, 2003) considers the non-saliency as the main cause of this slower processing. Behavioral researches have mainly focused on the reaction time of subjects during the processing of metaphors. The improvement of brain imaging technologies in recent decades has motivated researchers to use techniques such as ERP, PET, and fMRI, to study the processing of non-literal language including metaphors. Kutas, Federmeyer, Coulson, King, and Munte (2000) state that techniques with high temporal resolution, for example, ERPs and eye tracking, can help revealing how language processing unfolds over time. They can be used to track the availability of different sorts of linguistic information and the temporal course of their interactions. Since 1980, many researches, including Pynte, Besson, Robichon and Poli (1996), Tarrter, Gomes, Dubrovsky, Molholm, and Stewart (2002), Coulson, and van Petten (2002), Iakimova, Passerieux, Laurent and Hardy-Bayle (2005), Arzoan, Goldstein, and Faust (2007), Lai, Menn, and Curran (2009), Lai and Curran (2013) have used ERP and N400 to study metaphor processing. This research, using Event-Related Potential technique, studies the processing of literal and metaphorical sentences in Farsi and the role of conceptual mapping in this process. We anticipate literal sentences and conventional metaphors to be processed at a similar speed, but conventional metaphors are processed quicker than novel metaphors. In other words, more cognitive effort happen during the processing of novel metaphors. We also expect that conceptual mapping to occur during the conventional and novel metaphors in different ways. Four hundred sentences (literal, conventional metaphor, novel metaphor and anomalous) were made, then these sentences were designed by Psycopy software to be displayed on the computer screen. The brain electrical signals of 22 participants, were recorded during the reading task by a 64 channels EEG set made by Ant company and ASA lab software. The sample rate was 512 Hz, and the electrodes were arranged based on the 10-20 system. The signals were recorded from 32 electrodes. Using EEGLAB and ERPLAB, the mean amplitude of N400 in 7 areas including midline channels (Fpz, Fz, Cz, Pz, Oz), left medial channels (FC1, CP1, C3), right medial channels (CP2, C4, FC2), left lateral channels (CP5, F3, P3, FC5), right lateral channels (CP6, P4, F4, FC6), left peripheral channels (Fp1, F7, T7, O1) and right peripheral channels (Fp2, F8, T8, O2) were extracted. The data were analyzed by repeated measure (ANOVA) and pair-wise comparison (SPSS). The repeated measure analysis (ANOVA) showed that mean amplitude of four conditions: literal, conventional metaphors, novel metaphors and anomalous sentences in the midline, left and right medial and right peripheral were significantly different. Pair-wise comparison of the amplitude of 400 in 7 areas did not show any significant differences between literal sentences and conventional metaphors, but the pair-wise comparison of the mean amplitude of N400 in left medial channels showed a significant difference between conventional metaphors and novel metaphors processing. The Findings of this research showed that the processing of literal language and conventional metaphors take the same speed and cognitive effort. However, the processing of novel metaphors need more cognitive efforts, which can be considered as an evidence of conceptual mapping. Our findings are consistent with this premise that conceptual mapping in novel metaphors occurs through analogy and in conventional metaphors it happens through categorization.

Keywords: Figurative language processing, Conceptual, conventional, novel metaphor, Event-Related Potential, N400 -

Pages 151-175Within the broad domain of SLA, ‘pragmatic competence’ was brought to the fore following the assertation of communicative competence, but explicitly premiered in Bachman’s (1990) model of communicative competence, accentuating the significance of the relationship between “language users and the context of communication” (p.89). The vitality of L2 pragmatic competence alongside grammatical competence is the main motive behind the multitudinous number of studies carried out since the communicative revolution in language teaching in an effort to improve L2 pragmatics instruction. Ever since, a welter of studies have sought answers to three main questions as constituting the essence of interlanguage pragmatic competence research: whether and how pragmatic competence can be instructed, whether instruction is more effective than no instruction, and whether different instructional approaches addressing interlanguage pragmatics can be differentially effective (Kasper & Rose, 2002). Scholarships have corroborated that pragmatic features are amenable to instruction; however, more research is still needed to find out which interventional approaches and what type of instructional input and materials are more conducive to learning. One potential framework within which pragmatic competence can be investigated from an acquisitional perspective is Schmidt’s (1993) noticing hypothesis and Sharwood Smith’s (1981) consciousness raising. Since these postulations, a large number of studies have been conducted to substantiate claims as to the significance of learners’ pragmatic consciousness for interlanguage development. However, the pendulum has swung towards the production of speech acts, and comprehension of speech acts in interlanguage pragmatic competence seems to be an under-explored area of research. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the effects of implicit vs. explicit instruction on the pragmatic comprehension of two speech acts of apology and refusal being taught through video prompts. These two speech acts were opted because of their face-threating features. In doing so, a quasi-experimental pretest posttest research design was used. To this end, of 68 initial participants, 49 (F=33; M=16) intermediate EFL learners majoring English Literature and Teaching English as a Foreign Language from a state university were selected based on Oxford Quick Placement Test (2004). The age of these participants ranged from 18 to 33. These participants were randomly assigned into three groups: explicit, implicit, and control. The explicit and implicit treatment groups received two different types of instruction accompanied by specific tasks on pragmatic awareness using 60 video-driven prompts extracted from Prison Break movie series and Touchstone 2 video book series (Höst, 2006). The explicit group received metalinguistic explanation, feedback, and discussion, whereas the implicit group received implicit feedback through examples. In contrast, the control group did not receive any specific instruction on the use of apology and refusals and they were taught different sections of Touchstone 2. A validated Multiple-choice Discourse Completion Test (MCDCT) which consists of 128 items including 8 conversations for the speech act of refusal and 8 conversations for the speech act of apology was used. The results of running One-way ANOVA indicated that learners’ comprehension of speech act of apology and refusal across the two treatment groups developed after the treatment, and they outperformed the control group. Moreover, the explicit group outperformed the implicit group and the control group. The present paper recapitulates some pedagogical implications for materials developers, teachers, and learners. In the light of the results gained, it was proved that instruction had a positive influence on the pragmatic comprehension of apologies and refusals, substantiating that pragmatics is impervious to teaching drawing on dichotomous (explicit vs. implicit) approaches of language teaching. With respect to learning pragmatics, learners are advised to pay attention to the language forms, sociocultural facets of language and the germane contextual factors that could possibly affect the forms in the given context. The results suggest that sole exposure to contextualized input, video vignettes, may not necessarily result in students’ gain in pragmatics. Consequently, learning is augmented if the linguistic, analytic, and cultural features along with sociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic features are brought to learners’ attention. Moreover, when instructing various speech acts, sociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic features in the movies should be taught directly and explicitly which per se contributes to more pragmatic awareness and comprehension. Our findings are suggestive of the fact that scenes from movies serve as a contextualized source of pragmatic input inasmuch as they encompass a myriads of conversational exchanges in which the speaker’s reply does not provide a straightforward answer to the question. To obviate such a downside, audiovisual materials can be capitalized upon to enrich our language classes if students are provided with explicit feedback and practice. In a nutshell, it can be argued that sociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic features, through video-driven materials to simulate real life situations, should be juxtaposed in the textbooks by textbook developers and materials designers.Keywords: Pragmatic Competence, Implicit Instruction, Explicit instruction, Apology, Refusal, Noticing Hypothesis, Consciousness Raising

-

Pages 177-204

In India, the majority of people speak in one of the Indo-European languages, or more specifically, one of the languages derived from Sanskrit. However, in the southern part of this country there are several prevalent languages related to a family of languages that has existed since before the era of Indo-European languages, and these languages are still expanding and flourishing. This family of languages is called Dravidian, and the most important members are: Tamil, Telegu, and Malayalam. A family of languages with about 70 prevalent languages in Southern Asia belongs to the Dravidian family. They are more than 215 million people who speak in one of the Dravidian languages, who typically live in India, Pakistan, and Srilanka. The Proto-Dravidian language is the common mother language of all Dravidian languages, which has been reconstructed by linguists. The Proto-Dravidian language is divided into three sub families: Proto-North-Dravidian, Proto-Central-Dravidian, and Proto-South-Dravidian. A group of Dravidian speaking people have migrated to the borders of India and have taken residence in Aryan settlements. This group consists of Brahui in the Northwest, and Kurux and Malto in the Eastern India, the three of which belong to the family of North-Dravidian languages. Of these, the Brahui are the farthest with respect to geographical distance from their mainland, i.e. India. Almost none of the ancient characteristics of the Proto-Dravidian have been preserved by the Brahui. This language has been in contact with Indo-Aryan languages, such as Persian, for centuries and has been surrounded by these languages. At the moment, only five percent of the words used in Brahuidi language are of Dravidian origin. The Brahui language is the secluded member of the Dravidian family of languages and sometimes has been recorded as Brahuidi, Brahuigi, Bruhi, Bruhaki, and Kurgali. The first significant presence of Brahui in history goes back to the 17th century and the transcripts left by Mongols in Khanate Kalat. The Brahui language is spoken in Balochistan, mostly in the Pakistani part of the region. Brahui speakers also reside in Kalat, Karachi and Heidarabad, and most of them are Bilingual (Brahui and Balochi). The Brahui language consists of three main dialects: (1) Sarawani, (2) Jhalawani, and (3) Kalati. Because of the seclusion from other languages of the Dravidian family, and also multilingualism and minority of the speakers, this language has been influenced by the non-Dravidian languages in its proximity. During the past centuries, a group of Brahui people migrated to Iran by way of Pakistan and Afganistan border. According to experts and local speakers, the Brahui first entered Iran about three or four hundred years ago. A group of them has migrated from Sistan and Baluchestan to Southern Kerman and today most of them reside in Tom-meyri village, which is a part of Rudbar Jonoub division. About two centuries after migration and mingling with the people of Rudbar, they have severed all their racial and emotional ties with their siblings in Sistan and Baluchestan region. Due to being a minority, and the need to communicate with their hosts, they have learned the language of the majority (Rudbari language variety) and have used it in their everyday lives. In recent decades, the abundance of social changes have resulted in the addition of Persian to the collection of the languages used by this people, especially the youth and the middle aged. As a result of this trilingualism, their language variety is different from the Brahui languagespoken inBaluchestan. According to the statistics presented by the rural municipality of this village, the number of the Brahui who live in the region is 750 people and 155 households. Proximity with the people of Rudbar and mingling with them for two centuries have resulted in the assimilation of the Brahui with most of the cultural components of the Rudbari people. The Brahui are Muslims and they were followers of the Sunni tradition, but the Brahui of Rudbar have converted to Shiism. There is no difference between the clothing, traditions, customs, conventions, and rituals of the Brahui and the original people of Rudbar. Today, the only distinctions between the Brahui and the original people of Rudbar are the differences in appearance and language; that is, the Brahui of Rudbar are all trilingual. They speak Brahui among themselves, and use the Rudbari variety in their communications with the people of Rudbar, and they use verbal Persian in their contacts with other people. Two centuries of proximity and coexistence with the main natives of the region and the use of Rudbari dialect to interact with them have created a new variety of Brahui language, which we can call it the Brahui variety of Rudbar-Jonub. The research area is Tom-meyri village of Rudbar-Jonub. All the data in this study were field-specific and interviewed by male and female speakers (30) / from different age levels (from 9 to 100 years) and from different education. The purpose of this study is to describe the structure of verb in this variety. The verb is made in this variety by two forms; in some verbs, the verb is made on the basis of one stem. In other words, the stem implies only action. In others, the verb is made on the basis of two stems: past and present. Brahui of Rudbar-Jonub has 3 modes: indicative, subjunctive and imperative. This variety has 9 tenses: simple present, simple past, present continuous, future, imperative, past continuous, continuous past, present perfect, past perfect.

Keywords: Structure of verb, Language variety of Rudbar-Jonub, Dravidian Family, Rudbar-Jonub -

Pages 205-240

Language with a socially oriented nature is the realization of values, social behaviors and the ideologies as the unsaid and implicit proposition located in linguistic structures and function. Critical discourse analysis, like other hermeneutic methodologies, seeks to describe, interpret, and explain language across texts and socially oriented contexts. The present study is an attempt to investigate power differences and inequalities arising from discourse conventions, situational context and events in two different constitutional laws. These discursive conventions are ideologically-structured together within the orders of the texts and discourse of constitutions to naturalize the power relations. The emphasis in this study is upon the discursive structures not as a product rather as a dynamic process based on developing a triangulated theoretical framework of interrelated concepts and categories projecting power relations and facilitating the linguistic manifestations between discourse and other social and forensic elements through sociocultural changes at societal (national), regional, institutional and organizational levels in the early and middle twentieth century. To do the aims of this research and to find answers for the research questions both qualitative and quantitative approaches served the needs in this study. The qualitative data analysis of this study was based on critical discourse analysis inspired by Fairclough (2015), Hymes’s (1974) pragmatic approach, and the quantitative data analysis was based on 20 out of 50 social constituents of Van Leeuwen (2008) which was calculated through Chi square. The findings of this study manifested how lexical and textual choices have intensified and made some of the power relations more visible across the language from the section of people’s rights in both constitutions, Islamic Republic of Iran (1979) and Persian constitution (1906), to contrast and analyze the discursive and non-discursive structures of two aforementioned texts as well as to interpret and determine the discursive features, the social conditions of the century. Besides, the forensic contexts of these two texts should be related to three different strata of the texts: the linguistic environment in which the discourse occurs; the level of social institution which constitutes a wider interpretation and explanation for the discourse; and the level of forensic context as a whole. The social and forensic conditions which lighten the ideology, power relations and inequalities shape the linguistic production on the surface. Also, the pivots of gathering data were allocated to the social features proposed by Van Leeuwen (2008) such as the inclusion and the exclusion constituents as an evaluation method to contrast the lexical choices for language and power manifestations in texts such as “all and every versus none”, “dishonor versus offensive”, and “law versus Islamic law (religious law)”. The social interaction of these features was manifested through the linguistic choices in the constitutions. The subcategories of inclusion and exclusion are as follows: Inclusion: Nomination Objectivation Impersonalization Differentiation Personalization Identification Indifferentiation Specification Determination Appraisement Dissociation Assimilation Association Individualization Categorization Collectivation Exclusion Backgrounding Suppression The quantitative data were analyzed (applying SPSS software) through calculating Chi square (the non-parametric statistics) to compare the observed and expected frequencies of utilizing lexical choices in both texts.According to the research analysis, the theoretical framework focused and put forward a multiple method that represented the relations between language, power and context as three interrelated systems, in which there is an ongoing dynamic interaction. Consequently, this research proposed and applied an eclectic selection of discursive tools, a pragmatic context-based approach and socially oriented criticism as the most appropriate method to analyze forensic contexts of the constitution for Islamic Republic of Iran (1979) and Persian constitution (1906). This method as the eclectic includes discourse analysis, critical approach and forensic linguistics which intersect with each other and partly overlap, using different options, yet functioning as one structured whole, the members of which are interdependent. Based on the contrastive analysis of this research, the two texts draw on different interpretation in approaching the forensic context to distinguish the ideology and power relations in deeper strata. According to the findings, ideological formulations of power along with unequal relations dictated lexical choices in forensic text and manifested that discourse practices and orders of discourse represent ideological-discursive formulations along with power across linguistic disciplines. The power relations have special significance in the execution of laws and ordinances of Islam and in achieving just relations in society. The power also plays a vital role toward the ultimate goal of the critically discursive structures.

Keywords: Forensic-Critical discourse analysis, Discursive structures, Ideological formulations of power -

Pages 241-265

The present study was an attempt to compare the effect of teaching critical thinking and autonomy techniques on EFL learners’ speaking skill. There is of course ample research on critical thinking and autonomy in the ELT classroom. Qamar (2016) showed that autonomy teaching had a significant effect on EFL learners’ speaking while Karakoc (2016) demonstrated that critical thinking is no doubt necessary in language learning. Mall-Amiri and Sheikhy (2014) concluded that there was no significant difference between the impact of autonomy and critical thinking on EFL learners’ writing achievement. In another research, Vahdani and Tarighat (2014) found that critical thinking had a significantly positive impact on the speaking proficiency of Iranian female adult EFL learners. This aligns with the findings of a similar study conducted by Malmir and Shoorcheh (2012) in which they concluded that critical thinker is a better language learner. To the best knowledge of the researchers, there is no study comparing the effect of using critical thinking and autonomy improvement strategies on EFL learners’ speaking; hence, this research was conducted with the aforesaid purpose in mind to fill the existing gap in the literature. The present study set out to respond to the following research question:• Is there any significant difference between teaching critical thinking and autonomy on EFL learners’ speaking? Initially, the researchers piloted the sample PET and following item analysis, the modified version of the test was administered to 100 students through which 60 whose scores fell within one standard deviation above and below the mean were chosen as the main participants. Next, the 64 participants were randomly divided into two experimental groups of 32 in each: one as the autonomy group and the other as the critical thinking group. Once the two groups were formed, a statistical test was run on the participants’ scores on the speaking part of the sample PET to see if the two groups were homogeneous regarding their speaking ability prior to the treatment. The classes of the two groups were hold two days a week for a total period of seven weeks (14 sessions each lasting 120 minutes) and they took the same midterm test on the seventh session and the final test on the 14th session. Both groups were taught by the same teacher using the same materials. In one of these two experimental groups, the researcher used autonomy techniques during the course as treatment while in the other group, he taught the course using critical thinking techniques as the treatment. The design of this study was quasi-experimental posttest-only and comparison group. In this study, the independent variable was the type of instruction with two modes of practicing critical thinking and autonomy and the dependent variable was the learners’ speaking ability. The proficiency level of the participants and their age were the control variables of this study while the unequal number of males and females was the intervening variable. A series of descriptive and inferential statistics were employed in this research. For the homogenization process and speaking posttest, descriptive statistics was applied. The mean and standard deviation of the raw scores were calculated. The reliability of the sample PET was estimated through the Cronbach alpha formula and the Pearson Product Moment was used to estimate the inter-rater reliability between the raters for the writing and speaking sections. Ultimately, an independent samples t-test was conducted in order to test the hypothesis. All prerequisites for running parametric tests were also put in place beforehand. Following the treatment, the results of the independent samples t-test conducted on the posttest scores (t = 1.735, p = 0.008< 0.05) indicated that there was a significant difference between the mean scores of the two groups at the posttest with the critical thinking group who gained a higher mean score on the posttest compared to the autonomy group outperforming the latter and thus benefiting more in terms of improving their speaking. Following the rejection of the null hypothesis, the researchers were interested to know how much of the obtained difference could be explained by the independent variable. To determine the strength of the findings of the research, that is, to evaluate the stability of the research findings across samples, effect size was also estimated to be 0.82. According to Cohen (1988), this is a strong effect size. Therefore, the findings of the study could be strongly generalized. The result of the data analysis revealed that the critical thinking class enjoyed a far better performance in L2 speaking than the autonomy class. The present finding is in line with that of a good number of previous studies (discussed below) focusing on the effects of critical thinking and autonomy on L2 speaking among EFL learners. This study has certain pedagogical implications in favor of the application of critical thinking instruction in the ELT classroom.

Keywords: ELT, Speaking, Critical thinking, Autonomy -

Pages 267-295

Critical discourse analysis is a new branch of discourse analysis that addresses the cause and justification of contents and, in other words, the disclosure of information. Critical discourse analysis reveals the relationship among language, power and ideology through discovering discursive structures or features. Analyzing the discursive features of texts (stamps), the author intends to link them to the methods of representation of actors to reach hidden messages in texts and show that the methods of representation of actors are different, depending on stamp producers’ attitudes, and that stamps are directional. Text production, including image, seems to be a discourse, a social act. The effective use of language means that ideological constructions are indirectly presented to listeners through language. To realize this, language and discourse should include levels and layers. Language and discourse include ideology and the relations of power and domination at lower levels, and include discourse structures and events at higher levels. The present research aims to discover the hidden layers of stamp meanings within the framework of critical discourse analysis. Analyzing visual and written texts, the author explores how stamps portray language as evident, natural and inevitable culture and examine its different discourse, social and cultural functions. According to Fairclough (1989), critical discourse analysis represents communications kept hidden from the eyes of people in society. In critical discourse analysis, there is a tendency towards image analysis, as if images are linguistic texts. Van Leeuwen (1996) tried to create a theory and method to analyze multi-modal texts, which use different semiotic systems like language, image, or voice. Using elements, symbols and images, the discourse system of stamps is able to reproduce cultural and national identities in line with governments’ political, cultural, and social beliefs, and stamps use both visual and written layers to represent historical memory for one’s audiences. In fact, a stamp is a record of an event or presence that always persists over time and introduces a trace of represented memory of history. In the research, utilizing the Van Leeuwen pattern and analyzing stamps of the 50’s, the author intends to show that the writing style and ideology of text (stamp) designers and producers are represented within the discursive structures, and both interact closely. The main research questions include: How the discourse system of stamps can represent national identity process based on cultural and historical elements? What is the relationship between structural and visual elements and hidden power? The research methodology is from structure to content, which is reached by half a look at social semiotic image analysis from the point view of Kress and Van Leeuwen. In the research, for the analysis Van Leeuwen’s socio-semantic pattern is used. This pattern utilizes two main mechanisms, which are exclusion and inclusion, to represent social actors in a socio-semantic approach favorable by Van Leeuwen. In the research, purposive sampling was used. Therefore, 78 samples (39 stamps before the Revolution and 39 stamps after the Revolution) from stamps of the 50’s were analyzed by Van Leeuwen’s socio-semantic features qualitatively and quantitatively. It should be noted that the results obtained are generalized within the seventy-eight selected stamps, but not in general population, because giving a definitive answer to the research questions requires a very large sample and further research. In order to further clarify the first question, we checked the selected stamps of the 50s comparatively, based on the Van Leeuwen pattern from a socio-semantic perspective (according to discursive features), and found that the choice of images used in the stamps greatly depends on the rule based on which stamps had been published and are tools of transferring information from one generation to another. This is because using elements, symbols and images, the discourse system of stamps is capable of reproducing cultural and national identities in line with the political, cultural and social beliefs of governments. The majority of political, social, and cultural thoughts hidden in the heart of images are transferred through suppression and backgrounding features to their audience. Discourse features can be linguistic or socio-semantic, but by examining the images and the results obtained, it can be said that all the socio-semantic features do not necessarily have formal linguistic representations. An important point on socio-semantic features is that efficiency of socio-semantic features should be more in representing different discourse layers and in revealing the hidden meaning of the text. With regard to the second question, it can be said that the relationship between structural and visual elements in the stamp with power discourse varies according to statemen’s state functions, and the ideology governing the minds of the statesmen is reflected in the texts (stamps) by using specific discursive features, such as personalization, passivation, backgrounding, suppression, and other Van Leeuwen’s discursive features. In fact, there is a bilateral relationship between the discursive features and ideology. For this purpose, looking at the total findings from the statistical analyses, it has been found that some discursive features, such as backgrounding, suppression, collectivation, utterance autonomization, indetermination, passivation, differentiation and instrumentalization, have a higher frequency in the texts; while some socio-semantic features, such as individualization, functionalization, activation, association, personalization, nomination, indentification and spatialization, have a lower frequency. The motivation for the present research is to raise awareness and strengthen critical thinking, since one can consider critical discourse analysis as one of the most useful tools to examine texts in order to track the ideologies dominated on them. Van Leeuwen’s pattern of social actors is an effective pattern to do research in this area. In the authors’ view, such research can be used in the following organizations and institutions: The Organization for Educational Research and Planning of the Ministry of Education, International Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Deputy for Information and News Unit of IRIB, Deputy for Research of Universities (by holding conferences) (Disclosure: Raising university academic degree and rank, print and publication of educational book; Suppression: Income for university), Iranian Psychological Association, etc.

Keywords: critical discourse analysis, power, ideology, Socio-semantic features, Van Leeuwen’s pattern -

Pages 297-318