فهرست مطالب

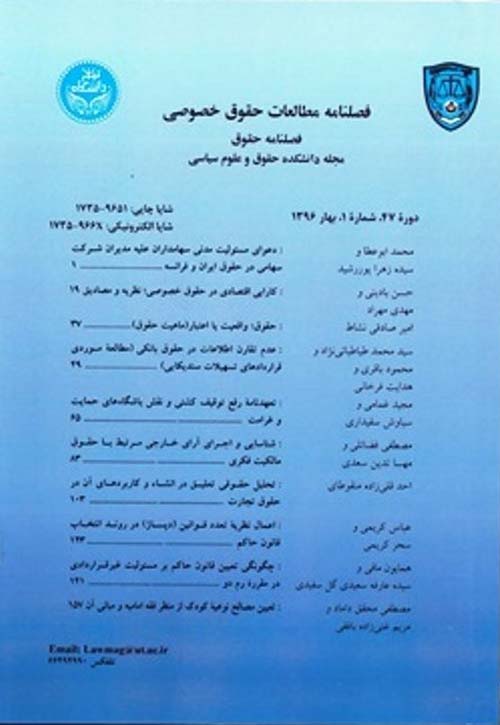

فصلنامه مطالعات حقوق خصوصی

سال پنجاه و یکم شماره 4 (زمستان 1400)

- تاریخ انتشار: 1400/12/03

- تعداد عناوین: 10

-

-

صفحات 605-626

از مهم ترین مراحل عملیات اجرایی، مزایده و فروش اموال منقول محکوم علیه یا متعهد است. اگرچه هدف از تحصیل حکم قطعی یا تنظیم سند لازم الاجرا، برای محکوم له یا ذی نفع سند، اخذ مطالبات یا اجرای تعهدات است، پژوهش حاضر که از نوع توصیفی- تحلیلی است، درصدد پاسخگویی به این پرسش است: آیا به صرف صدور حکم یا تنظیم سند، چنین هدفی حاصل می شود؟ در واقع، اجرا که ادامه فرایند دادرسی و صدور سند است، در مراجع قضایی و ثبتی به سهولت انجام نشده، به دلیل موانع و مشکلات متعدد، مسیر عملیات اجرایی، به ویژه در خصوص مزایده اموال، با چالش های جدی مواجه است. بسیاری از این مشکلات ناشی از سکوت قانونگذار در بیان بعضی احکام و مقررات مزایده، از جمله حذف مقررات حراج در نظام اجرایی ثبتی، سکوت درباره تجدید مزایده، نبود ضابطه در تعیین زمان و مکان فروش، عدم تبیین یا ابهام در آگهی مجدد و روزنامه کثیرالانتشار محلی و نیز تعدد اموال بازداشت شده است، در نتیجه لازم است قانونگذار در این زمینه گام موثری بردارد. ازاین رو رفع آنها در گرو بازنگری و اصلاح مقررات مربوط است.

کلیدواژگان: آگهی اضافی، تعدد اموال، حراج، محل فروش، موعد فروش. -

صفحات 627-648

نقش تجاری فرمانده در صحنه تجارت دریایی و مدیریت اداره کشتی، جایگاه ویژه ای به او بخشیده است تا در شرایط اضطراری که به پایان رساندن سفر، مستلزم اقدام سریع اوست، بدون وجود اختیار واقعی بتواند به منظور تامین خدمه، تعمیر کشتی، تامین نیازهای اساسی و... به نمایندگی از مالک، اقدام کند. اقتدار فرمانده، گاه تنها برگرفته از ظاهری مشروع و متعارف و در نتیجه تصور معقول ایجادشده برای دیگران است. حمایت از اشخاص ثالث با حسن نیت که با اعتماد به وضع ظاهری و با تلقی ماذونیت، به معامله با فرمانده نشسته اند، به تحقق نمایندگی ظاهری او انجامیده است. در این مقاله به این قسم از نمایندگی و شرایط تحقق آن که در معاملات فرمانده همچون فروش کشتی، رهن آن، فروش و رهن بار، اجاره کشتی، صدور بارنامه و مداخله در فرایند دادرسی، نمود عمده خود را می یابد، خواهیم پرداخت.

کلیدواژگان: حسن نیت، شخص ثالث، فرمانده، نمایندگی ظاهری. -

صفحات 649-671در ترجمه متون ایران باستان، واژه «داد»، «دات» یا «داتا» را اغلب معادل «قانون» گرفته اند. اما دقت در مفهوم «قانون» و همچنین تحلیل نحوه کاربرد «داد» در متون مذکور نشان می دهد ترجمه «داد» به «قانون»، به خصوص از دیدگاه حقوقی، نادرست است. «قانون» در ساده ترین تعریف، قاعده رفتار است، اما یک قاعده منفرد برای یک موضوع مشخص. «داد» اگرچه به «همه قواعد» و «قانون مندی» اشاره دارد، هیچ گاه به معنی یک قاعده منفرد و معین به کار نرفته است. «داد» قانون نیست، بلکه «آیینی» است که قانون می تواند از آن برآید. اگر «قانون» مستقیما، عینا و دقیقا یک قاعده است، اما «داد» و در مفهوم وسیع تر - «اشه»- کیفیت آرمانی و «پیش از آمیختگی» کیهان را توصیف می کند و در نتیجه می تواند شکل درست زندگی را نشان دهد و تبعا اقتضایات هنجاری داشته باشد. علاوه بر «داد»، واژگان دیگری نیز به «قانون» ترجمه شده اند که هیچ کدام مناسب این معنا نیست. اساسا متون پهلوی تمایلی به استفاده از مفهوم «قانون» ندارند، چه بسا ادبیات حقوقی ساسانی فاقد واژه ای برای این معنا بوده است.کلیدواژگان: آیین، اوستا، حقوق ساسانی، دین زرتشتی، قاعده، متون پهلوی.

-

صفحات 673-693

بانی نظری نظام بهره برداری از منابع آب در حقوق، مبتنی بر نظریات گوناگونی است که می تواند از مالکیت مطلق مالک اراضی، نظریه حریم، نظریه حق تقدم، نظریه احراز و نظریه امانت عمومی را در برگیرد. این نظریات که در طول تاریخ حقوق، مبانی حق بهره برداری منابع آب را فراهم آورده اند، در نظام فقهی و حقوقی ما نیز کم و بیش مورد استناد بوده است. در فقه امامیه هرچند بنا به قاعده فقهی «من حاز ملک» حق بهره برداری آب را مبتنی بر نظریه احراز دانسته اند که همگان در بهره مندی از آب های مباح حق برابر دارند و هر کس زودتر آن را حیازت کند دارای اولویت خواهد بود، اما قانون اساسی و قانون توزیع عادلانه آب ذیل مفاهیم انفال و اموال و مشترکات عمومی از نظریه ای پیروی کرده اند که با نفی نسبی مالکیت خصوصی و عمومی، مدیریت و نظارت بر نظام بهره برداری از منابع آب را با رعایت مصالح عامه در اختیار دولت قرار داده است. ازاین رو می توان مبنای نظام بهره برداری از منابع آب در ایران را در چارچوب نظریه ای موسوم به «نظریه امانت عمومی» ارزیابی کرد.

کلیدواژگان: احراز، امانت عمومی، انفال، حریم، حقآبه، مشترکات. -

صفحات 695-715

وسایل نقلیه خودران، فناوری هایی هستند که توسط هوش مصنوعی از قدرت تصمیم گیری و تجربه آموزی بهره مند شده اند. این وسایل نقلیه که با حسگرهای متعدد اطلاعات فراوانی را جمع آوری می کنند، از طریق اینترنت اشیا با یکدیگر و با همه چیز در ارتباط اند و اطلاعات را در شبکه هایی منتقل می کنند که در دسترس تاسیسات شهری و جاده ای قرار می گیرد؛ اطلاعاتی که می تواند منتسب به شخصی باشد و ذیل حریم خصوصی وی بیاید. در چنین شبکه هایی، حریم خصوصی اشخاص با خطرهایی مواجه می شوند که قانونگذار باید آنها را به منظور پیشگیری از نقض حریم خصوصی بشناسد. تحقیق حاضر تعابیر حریم خصوصی در قوانین کشورهای اروپایی و ایالات متحده آمریکا، و اندیشه ها تا تعبیر مناسب را بیابد، و از رهگذر ویژگی های وسایل نقلیه خودران، مربوط به نحوه جمع آوری و به کارگیری اطلاعات در مراحل چرخه حیات اطلاعات، و مطالعه پرونده ها، محققان و قانونگذار را با خطرهایی آشنا می سازد که در استفاده از این فناوری متوجه حریم خصوصی می شود و به فراخور هر مرحله الزاماتی حقوقی را برای پوشش این خطرها معرفی می کند.

کلیدواژگان: اطلاعات شخصی، چرخه حیات اطلاعات، داده های شخصی، فناوری خودکار، هوش مصنوعی. -

صفحات 717-737

هر دعوا به طور طبیعی دارای ارکانی است و رای داوری نیز براساس دعوا صادر می شود. این واقعیت به طور طبیعی این پرسش را پیش می کشد که آیا ارکان دعوا باید در رای داور منعکس شوند یا خیر. اگر بر این عقیده باشیم که ذکر ارکان دعوا ضروری است، پرسش دیگری پیش می آید در خصوص اینکه ارکان دعوا کدام اند. به همین ترتیب باید به این پرسش پاسخ گفت که ضمانت اجرای عدم بیان ارکان دعوا در رای داوری چیست؟ در این پژوهش رای داوری به مثابه آیینه دعوا دانسته شده و بر این اساس بیان ارکان دعوا در رای داوری ضروری تشخیص داده شده است. با چنین فرضیه ای طبیعی است که برای عدم بیان ارکان دعوا در رای داوری ضمانت اجرایی در نظر گرفته شود. به نظر می رسد ضمانت اجرای عدم بیان ارکان دعوا (اصحاب، سبب و موضوع دعوا) حسب مورد می تواند ضمانت اجرای بطلان رای داوری یا لزوم اصلاح رای داوری را در پی داشته باشد. عدم ذکر اصحاب دعوا در صورت قابل اصلاح بودن رای، نباید سبب ابطال یا عدم شناسایی آن شود. اما عدم ذکر موضوع دعوا بدین سبب که امکان نظارت قضایی و بررسی اعتبار امر قضاوت شده را برای دادگاه با دشواری مواجه می سازد، خلاف نظم عمومی و از موارد ابطال رای داوری است. عدم بیان سبب دعوا نیز چون منتج به غیر مستدل بودن رای می شود، مخالف نظم عمومی و از موارد ابطال رای است.

کلیدواژگان: ارکان دعوای داوری، ارکان رای داوری، اعتبار رای، ضمانت اجرا، نظم عمومی. -

صفحات 739-761

بحث از مسیولیت مبتنی بر تقصیر و نقش تقصیر در تسبیب، اگرچه از مباحث مورد توجه فقها بوده و نتایج مهمی بر آن مترتب است، با این حال در کتاب های فقهی به طور مستقل به آن پرداخته نشده و فقیهان مفهوم واقعی رابطه سببیت را به روشنی و از حیث نظری تبیین نکرده اند و فقط گاه در ضمن مثال ها و احکام صادره از جانب آنان، دیدگاهشان قابل دریافت است. بر این اساس می توان گفت که عده ای در ضمان ناشی از تسبیب، تقصیر را شرط ندانسته و صرف ایجاد ضرر و رابطه سببیت را برای وجوب ضمان کافی می دانند، در مقابل عده ای دیگر بر این باورند که در تسبیب، بدون احراز عنصر تقصیر ولو تقصیر نوعی قابلیت انتساب ضرر وجود ندارد. این گروه معتقدند مطابق تعریف فقها، سبب در باب اتلاف آن است که فعل عادتا برای ایجاد تلف به کار رود، همچنین به قاعده فقهی «المتسبب لایضمن إلا بالتعمد» استناد می کنند که شرط ضمان را تعمد می داند، مضافا آنکه از نظر آنان روایات وارده، سبب موضوع حکم قرار نگرفته، بلکه مدار مسیولیت در تسبیب مبتنی بر قابلیت انتساب عرفی ضرر و احراز تقصیر عامل است، دیدگاه های حقوقدانان نیز همین مسیرها را پیموده و این اختلاف آرا نیز در میان آنان مشاهده می شود، به نظر می رسد با توجه به مصادیق فراوان و بعضا پیچیده ای که در این زمینه وجود دارد و نظر به تنوع روابط اجتماعی و حقوقی میان انسان ها، مبنا قرار دادن یکی از این دیدگاه ها برای همه حالات و تمامی مصادیق منطقی نباشد، بلکه راه حل اصولی و قابل پذیرش، مراجعه به عرف و معیار قرار دادن آن برای اثبات یا عدم اثبات تقصیر است.

کلیدواژگان: اتلاف، انتساب، تسبیب، تقصیر، ضمان. -

صفحات 763-782

تولد تقویمی، سزارین خارج از موعد مقرر و بدون ضرورت پزشکی است که صرفا هدف آن تولد نوزاد در تاریخی خاص است. این نوع از تولد به دلیل تغییر فرایند طبیعی زایمان ممکن است خطرهای اجتناب ناپذیری را برای مادر و نوزاد به همراه داشته باشد؛ ازاین رو با تمسک به روش کتابخانه ای درصدد شناسایی مسیولان ورود خسارت بر خواهیم آمد. تولد تقویمی افزون بر آنکه مغایر با اخلاق است، از نظر قانونی نیز برای مداخلان در آن مسیولیت مدنی، کیفری و در مواردی انتظامی ایجاد می کند. احراز ارکان مسیولیت مدنی در تولد تقویمی اعم از ورود ضرر، فعل زیانبار و رابطه سببیت، موجبات مسیولیت مدنی پزشک، والدین و مراکز درمان را فراهم می آورد. پزشک در چنین تولدی به عنوان فرد آگاه و خبره، مباشر تولد نابهنگام است و والدین با اعلام رضایت به سزارین خارج از موعد، سبب تولد تقویمی محسوب می شوند. در کنار این دو عامل مراکز درمان با وجود رابطه استخدامی پزشک و قرارداد منعقده بین بیمارستان و بیمار، سبب دیگری بر وقوع خسارت احتمالی اند؛ ازاین رو مطابق ماده 526 قانون مجازات اسلامی، در فرض اجتماع سبب و مباشر، براساس تاثیر میزان رفتار عاملان و به واسطه احراز آن توسط معیار عرفی، مسیولیت جبران خسارت توزیع می شود.

کلیدواژگان: اجتماع سبب و مباشر، پزشک، تولد تقویم، ضمان، مراکز درمان، والدین. -

صفحات 783-805

وابستگی متقابل عوضین در عقود معوض و لزوم اجرای عدالت معاوضی موجب شده است تا حق حبس، به عنوان یکی از راه های اجبار طرفین عقد به اجرای تعهدات، پذیرفته شود. اما قلمرو آن در قانون مدنی به درستی تبیین نشده و صرفا در مبحث بیع، حق حبس برای بایع و مشتری مقرر شده است و اعمال آن در سایر عقود معوض به ویژه شناسایی و اعمال حق حبس در مرحله انحلال قرارداد مورد تردید است. این پژوهش، به شیوه توصیفی -تحلیلی، با اعتقاد به وجود مبانی مشترک حق حبس در دو مرحله اجرای تعهدات قراردادی و استرداد عوضین در زمان انحلال، در پی شناسایی حق حبس به عنوان یک قاعده عمومی در اجرای تمام تعهدات معوض است. بنابراین، حق حبس محدود به مرحله انعقاد قرارداد نیست و به مرحله استرداد عوضین در زمان انحلال قرارداد و حتی در تعهدات متقابل ناشی از ضمان قهری مانند غصب تسری می یابد.

کلیدواژگان: استرداد عوضین، تقابل عوضین، حق امتناع، عدالت معاوضی، عقد بیع. -

صفحات 807-826

ماده 21 گات متضمن استثنای امنیت بر تمامی تعهدات اعضای سازمان جهانی تجارت است. تفسیر آن ماده از ابتدا محل تشتت بوده است. برخی کشورها و نیز مفسران بر آن بوده اند که استناد یک کشور به آن ماده قابل اعتراض توسط سایر اعضا نیست و رکن حل اختلاف نیز صلاحیت رسیدگی به اختلاف های ناشی از استناد بدان ماده را ندارد. در مقابل، برخی کشورها و مفسران قایل به صلاحیت رکن حل اختلاف در خصوص دعاوی ناشی از این ماده بوده اند. هیات حل اختلاف در دعوای روسیه- اوکراین موسوم به دعوای روسیه- اقدامات مرتبط با محموله های در ترانزیت، با تشبث به اصل حسن نیت و نیز تفسیر لفظی، به تفسیر ماده 21 پرداخت. جستار حاضر نشان می دهد که هرچند به سختی می توان از اصول تفسیر معاهدات به معنای مشخصی نایل آمد، با این حال اصل تفسیر مبتنی بر حسن نیت، به عنوان یک اصل حاکم بر تمام مقررات سازمان جهانی تجارت، صحت تفسیر دوم را اثبات می کند.

کلیدواژگان: استثنای امنیت، اصل حسن نیت، سازمان جهانی تجارت، ماده 21 گات، هیات حل اختلاف.

-

Pages 605-626

One of the most important steps of enforcement operations is the high tender and sale of moveable properties of the losing party or promisor (debtor). Although the final objective of the winning party or beneficiary, in obtaining a definitive judgement or drawing up a binding document, is the collection of claims or the implementation of undertakings, if the relevant judgement or binding document is not implemented, the final objective of establishing and implementing the religious and legal justice will not be achieved. The present study, by a descriptive and analytical method, is seeking to answer the question whether by mere issuance of a judgement or by drawing up a document, such an object is accomplished or is faced with some challenges and obstacles. Indeed, the enforcement path, which constitutes the continuance of proceedings process and the issuance of document, , will not be easily attained before the judicial and registration authorities and, due to the multiple problems and impediments in this process, the path for enforcement operations, in particular with regard to the high tender of moveable properties will encounter with serious tardiness and challenges. Many of these problems can be attributed to the Legislature’s silence about articulating some rules and regulations with regard to high tender including elimination of auction regulations in the registration enforcement system, and about questions like the renewal of high tender, the authority competent for determining whether the properties distrained according to the Bylaw for the Enforcement of the Contents of Binding Notarial Documents (1386 SH) should be returned and the time they should be returned , lack of any specification regarding mutual consent on the place and the time of sale in the registration regulations, lack of any criterion for determination of the place and the time where the high tender and the sale must be executed, failing to make clear the concept of ‘local widely-circulated newspaper’ and ambiguity regarding the ‘renewed notice’ and the ‘renewal of notices’, lack of any specification with regard to joint ownership for the sale of movable properties in the Registration Bylaw and, finally, conflicts in certain articles of the Act for Enforcement of Civil Judgements (1356 SH) and in the Registration Bylaw. It is as a result of these problems that the concerns of the beneficiary persons must be understood, as these shortcomings and problems hinder or obstruct the enforcement operations by judicial and registration authorities. On the other hand, since the enforcement of judgements and documents is made through two different notarial and judicial enforcement systems, despite the similarities in the regulations governing, and the methods applied in, the enforcement by either system, there exist many differences between the two. By elimination of the regulations of auction and elucidating the relevant rules of high tender, the law has disarranged both the legal system and the enforcement system of these two legal institutions. Considering the differences between auction and high tender, the elimination of the regulations of auction and its replacement by high tender has created crucial difficulties as well as perplexities. Because, the institution of auction continues to exist in other laws, such as Art. 2 of the Guild System Act (1383 SH) in which the which defines auction by three charactersitics: in-person transaction, cash payment and definitiveness. But, despite the evolutions in the electronic processes in notarial agencies, no authority has yet been assigned for the enforcement of the high tender operations or for the electronic auction. Hence, considering the high prevalence of auctions, in particular the electronic ones, differentiating between high tender and auction and the elucidation of their rules and consequences in the 1356 Act and the 1386 Bylaw, by amending or revising the respective rules, is a necessity. Other problems to be attended include the law’s silence about the second-turn high tender, about the place of keeping and protecting memory and about the definition and instances of ‘local newspapers’, as well as judicial rules and notarial regulations which are inconsistent with, or contradicts, one another in one respect or another. These problems and inconsistencies that make necessary, first, that the Bylaw for the Enforcement of the Contents of Binding Notarial Documents (1386 SH) be given the status of an act of Parliament and, second, that the Act for the Enforcement of Civil Judgements (1356 SH) be wholly revised considering of the long time since it was enacted.

Keywords: Auction, Multiplicity of Properties, Sale Time, Sale Place, Additional Notice -

Pages 627-648

The authority of a captain is not limited to the technical management of the ship during the voyage and the administrative duties concerning the interaction with the administrative organizations located in commercial ports. The captain has, moreover, a special place arising from his role in the maritime trade scene and his role in managing the ship that allows him to act on behalf of the maritime carriers in the transaction or to take other necessary measures in crew recruitment, ship repair, fulfillment of basic needs, etc. in emergencies where the completion of the voyage is subject to prompt action by the captain. The captain's authority is sometimes deemed to stem from the legitimate and conventional appearance and, consequently, from the reasonable perception created for others. However, he does not have such authority in reality. So, the question arises as to whether the shipowner's defense that captain has acted beyond his authority, if proven, is admissible and precludes the legitimate expectations of the other party to the contract about the owner’s commitment to the consequences of the captain’s acts. In other words, can the captain's authority be extended and can he be considered the shipowner’s agent? In response to this question, legal doctrine and jurisprudence have suggested the apparent agency of the captain in support of third parties in good faith who deal with the captain by trusting in the appearance and considering his authoritativeness. In this study, this type of agency of the captain in his interventions is examined in the domestic and foreign legal system. The results indicate that the apparent agency of the captain is represented mainly in his transactions such as ship sales and mortgages, cargo sales and mortgages, ship rental, crew recruitment, and bill of lading. The apparent agency leads to the liability of the ship owner making him responsible for fulfilling obligations arising from the acts of the apparent agent. Although the advancement of knowledge and the development of communication tools in recent years have made it possible to communicate with the owner and ask him for instructions, the notion of the impossibility of extraordinary intervention of the captain as an apparent agent is hardly acceptable. Accordingly, the legal doctrine today emphasizes the apparent agency of the captain, focusing on his specific role and scope of authority as one of the major bases of the apparent agency. In line with the legal literature, the rulings of foreign courts on a variety of issues uphold the captain's authority to steer ships from the port of loading to the port of discharge. The captain's intervention on behalf of the shipowner is sometimes expanded to the point where court documents are sent to him rather than to the owner or even where he is considered a defendant himself, and sparing him from this status is ruled to be void. Although the legal systems has come to hold the view that the captain lacks the authority to sell the ship, his authority in mortgaging the ship and cargo is a point of contention, each legal system having its own position, with minor disagreements within each system. Following Article 28 of the Iranian Amendment to the Maritime Act approved on 9/18/2012, which has replaced Article 89 of the Iranian Maritime Act, obtaining permission from the shipowner, the sender and the cargo owner is a necessary condition for mortgaging the ship. Although the legislature may appear to want to reduce the captain's authority and, consequently, to strip him of his apparent agency, according to the Paragraph A of the above-mentioned article, the captain is still eligible to receive a loan if necessary funds are not provided by the owner or in necessities when urgent interventions are necessary. Moreover, according to Article 33 of the Amendment to the Maritime Act, which has replaced Article 94 of the Maritime Act, the deficiency of the latter, which failed to determine the legal status of the unjustified sale of the cargo, has been eliminated, and by confirming its validity, the apparent agency of the captain in the sale of cargo has been explicitly acknowledged.This agency can also be sustained in concluding a lease in the event of an emergency. Besides, due to the special place of the ship certificate of registry in establishing the ownership in some legal systems such as the French Law, if the tenant's name is not mentioned in the bill of lading, the owner, being named in the ship certification of registry, is considered responsible for the captain's obligations. The apparent agency of the captain in issuing the bill of lading now enjoys an almost consensual endorsement among legal systems of the world.

Keywords: Captain, Apparent Agency, third party, Good Faith. -

Pages 649-671This article is part of a larger study of the philosophy and history of law in Iran. Philosophical studies in Iranian law need to begin with the examination of the most fundamental legal concept, namely the “law” itself. The study of the concept of law, in turn, can begin, as it has been the tradition of old scholars, with a semantic survey of the word “qānūn” (the Persian word for ‘law’). But since “qānūn” is a foreign word that came into Persian after the arrival of Islam, the first step would be to find the word that the ancient Iranians used for “law”. A brief look at the ancient texts and their translations shows that the Iranologists and translators have often translated the word “dād”, “dāta” or “dātā” to “law”. However, considering facts such as a) that, in Pahlavi texts, one of the definite meanings of “dād” is religion/“Aeen”; b) “dād” was used in the oldest texts and poems in New Persian (Dari) in the same meaning as Aeen and that it has apparently never been used to mean “law”; c) that there is no other New Persian word equivalent to “law”; d) New Persian is very similar to Middle Persian (Pahlavi) and there is not a long interval between the prevalence of Middle Persian and the first New Persian texts and poems , this hypothesis arises that in spite of what Iranologists suppose, “dād” in ancient Iranian texts does not signify the law. To find an answer to the research question and verify the hypothesis, we first need to provide a definition of the “law” as part of the theoretical and conceptual framework of the research. Hence, the definitions of “law” given by jurists and legal philosophers will briefly be reviewed. Then, in order to avoid imposing modern conceptual structures and ideas on ancient Iranian texts, as well as to expand the scope of the definition to include all possible examples, some elements of this definition will be set aside so that the law in its simplest definition - the rule of behavior – remains as the basis for this research.Then, a sufficient number of Pahlavi texts and almost all Achaemenid inscriptions will be studied. The research method will be first to examine the translations of ancient texts and, wherever the translators have used the word “law”, to study the transcripts of the original texts in order to find out which words in the original text the translators have taken as equivalents of the law . In other cases, the transcripts of the original texts will be checked first. Wherever the word “dād” is used, translations will then be checked to find out what equivalents the translators have suggested for it. In the last step, by comparing and analyzing sentences and phrases, paying attention to their context, and considering the information available from ancient Iran, the equivalents that translators have suggested for the word “dād” will be evaluated. The results of this study will show that the translation of “dād” to “law”, especially from a legal point of view, is incorrect. “Law”, in its simplest definition, means a rule of conduct, but a single rule for a particular subject. Therefore, if the translation of “dād” to “law” was correct, then it should be possible to find a text in which “dād” means a single, particular rule. It should also be possible to find uses of this word in plural and in indefinite forms, uses such as in “there is a “dād” that stipulates that this must / must not be done”, or in “this text/book contains a few “dād”s applicable to ...”. But the findings of this research do not suggest such a thing. Though “dād” does refer to “all rules”, “being organized by rules” or “legality”, it has never been used to mean a single, definite rule. “Dād” is not law, but a part of a weltanschauung, cosmology or ideology from which the law can be derived. If “law” is directly, exactly and essentially a rule, “dād” and “asha”, a more comprehensive concept, describe merely the utopian state of universe before being invaded and polluted by Ahriman. They can thus illustrate the righteous forms of life, with certain implications about rules and norms. Perhaps it is why the 8th book of Denkard describes “dād” as the knowledge related to material world (Giti). Once it becomes clear that “dād” could not signify the law, the subsidiary question would arise what word was used for this concept in ancient Iran? Reviewing ancient texts shows that in addition to “dād”, some other words have been translated to “law” none of which, however, are suitable for this meaning, as neither is semantically connected to the concept of “law” even to the extent that “dād” is. Since the analysis of Pahlavi legal texts indicates that they do not tend to refer to the concept of “law” and given that the search to find a word equal to “law” in some of the most important legal texts of the Sassanid period fail, this article reinforce the hypothesis that the Sassanid legal literature lacked a word for “law”. Definitive confirmation of this hypothesis requires complete review of all Pahlavi texts. Finding a convincing answer to this question is one of the most important steps that can be taken in studying the history and philosophy of law in Iran.Keywords: Avesta, Pahlavi texts, Religion, rule, Sassanid law, law, Zoroastrianism

-

Pages 673-693

Due to its predominantly arid and water-deficient climate, Iran faces the challenge of dehydration. The rate of exploitation and consumption of water resources plays some role. Iranian civil law, which is the first law governing the processes of water resources exploitation, inspired by Shi’i law, has based its relevant rules on theories such as absolute ownership of land, priority, privacy, and acquisition. The theoretical bases of the legal system of water resources management is thus based on private property, which along with the development of new technologies of drilling and exploitation has led to uncontrolled consumption of water resources. Therefore, the revision of these theoretical foundations is necessary in order to limit and regulate the exploitation of water resources. The first theory listed above, absolute ownership of land, crystallized in Article 96 of the Civil Code, holds that whoever owns a piece of land has the absolute ownership of the water resources under it and can use them however he wishes without any restrictions. Apart from giving rise to disputes among, A second theory, the right of precedence, regulates the use of water resources based on the date of first discovery and exploitation, which is an implication of the precedence rule in Shi’i law according to which prearrangements for reclamation of resources is a basis for priority in possession. . A third theory, territory of land (harim), is another basis granting the owner of a piece of land surrounding a surface water source such as a river or lake the right to own and exploit these water resources. Accordingly, the ownership of water is a function of the land ownership, and there is no right to transfer the ownership of water, independent of the adjacent lands. Some jurists in these cases have relied on the rule ‘Al-Aqrab fa al-Aqrab’ (‘Who is closer takes priority’), based on the fact that whoeveris closer to the water stream, is superior to others, and Article 156 of the Civil Code has been influenced by this theory. But the theory of attainment,which has more supporters in Shi’i law, is based on the possession of water., According to this everyone owns any amount of water that he or she obtained through the possession and branching of surface water or digging wells and aqueducts. Article 149 of the Civil Code regarding the possibility of acquiring surface water and Article 160 of the same Code governing the digging and acquisition of wells and aqueducts have been taken from this theory. These theories, which have led to the private ownership and management of water resources, have led to the development of mechanized methods of exploitation and, in turn, to the destruction of water resources. Articles of civil law and other regulations that are influenced by the aforementioned theories, on the one hand, and a tendency towards a state-centered view of public ownership, on the other, as in the Law of Equitable Distribution of Water, which recognizes the government as the owner of water, by applying proprietary behaviors, makes it an instrument for its economic and social policies, has permitted the unwarranted exploitation and has exacerbated the water crisis. Therefore, based on the environmental needs and the international trends viewing water as a national asset belonging to future generations, this article seeks a theory that can be based on environmental, jurisprudential and legal principles and provides grounds for revising laws and regulations governing the ownership and management of water resources, in particular Articles 149 to 160 of the Civil Code, which make water a common property that is open to free acquisition and private ownership. Accordingly, Article 1 of the Law of Equitable Distribution of Water, enacted in 1982, which is influenced by Article 45 of the Iranian Constitution, has a great potential to change the approach to the ownership of water, based on the concept of public trust, private ownership to one based on the concept of trust. The article relies on the explicit use of the word trust in the Law to lead to more effective policies and regulations in the protection of water resources and in the issuance of licenses for its exploitation, and to prevent unrelenting competition in the consumption of this common resource and uncontrolled harvesting and drastic reduction ofthe country's water reservoirs. This article uses an analytical and descriptive research. Relying on library resources it studies different perspectives in order to answer the question what is the basis of the right to use water resources in the jurisprudential andlegal system of Iran and which theoretical bases can be selected for it. to ensure protection and preservation of water resources. It first suggests and examines various theories, and then seeks to formulate, under the final theory which is based on the concept of public trust, a view in accordance with environmental conditions and water resources crisis based on Islamic legal principles. By amending existing laws and regulations, water can be used as a trust in the hands of the government in the public interest.

Keywords: Achievement, Anfal, Commonalities, Public trust, Privacy, water rights. -

Pages 695-715

The idea of a smart city conveys devices highly equipped with novel technologies performing in place of human beings. For a city to be smart, information flow plays an underpinning role. Devices in smart cities collect enormous amounts of information, enabling their embodied systems to run either as computers tackling ordinary tasks or as intelligent agents making decisions and gaining experiences. Artificial intelligence (AI) and other algorithmic systems in both learning and performing stages rely on learning from information entered by a programmer and transmitted from an external source. AI, in particular, benefits from information to predict the future, make decisions, and use feedback on prior ones for decisions on similar occasions. Therefore, the more information at hand, the more efficient AI performs and the smarter the city is. The growing communication technologies such as 5G internet and the internet of things (IoT) let AI systems access transmitted information at higher rates. Autonomous vehicle (AV) is one of the features by which smart cities are known. Along with IoT and the 5G internet, which make information transfer from other devices and infrastructures faster, AVs benefit from numerous embodied sensors collecting various sets of information from the environment for AI to participate in the vehicles' functions. In a city where people use AVs alongside other smart devices, collecting and transmitting information raises privacy concerns. This study deals with the growing concern over the privacy of the information on which AVs rely to operate. The study's primary purpose is to detect the potential privacy threats by describing the underlying features of AVs in the implementation of which information plays an essential role. Then, considering the potential threats, the researchintroduces and criticizes the current privacy protections in principle and practice, associable with AV's inherence.The study dedicates Section I to the concept of privacy to illustrate the evolution of its definition, dimensions, and legal protections as technologies grew over time. Dividing the process into three courses in which privacy relates different meanings, the study suggests that privacy within the current course is falsely comprehended through data and data protection regulations when instead of information itself, the aim of protection must be the subject person whose information is collected. Not considering different dimensions, the current interpretation provides narrow protection for privacy, although it empowers data transactions where data is not sensitive and the subject person consents. Some recent regulations in the EU and the USA, namely General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and California Privacy Act (CPA), deal with privacy in this sense by protecting data in the collection, transmission, storage, and usage stages against unconsented processes in the technology sector and technological systems, one of which being AVs. Section II provides details on how information flow and IoT enable inter-connected AVs to operate, then elucidates how the usage of such inter-connection has threatened different dimensions of privacy in actual technology cases similar to AVs. There are cases in which different sets of information on people's location, state of body and mind, behavior and action, social life, and media are collected and transmitted in vehicle-to-vehicle, vehicle-to-infrastructure, and vehicle-to-everything networks unconsented or illegally processed. Outlining the four stages of the life cycle of information (collection and storage, processing, usage, and transmission), Section III demonstrates whether AVs impose the risk of breach of privacy by four types of behavior (collection, processing, dissemination, and invasion) and how the current regulations protect privacy in the said types of behavior. Primarily, privacy protection in AVs entails considering legal principles in the design stage as well as the stages of the life cycle of information to guarantee the security and transparency of information flow. Confidentiality and encryption to improve security and inform the data subject of the purpose of processing and implementing data to increase transparency are the legal principles envisaged by current regulations, GDPR and CPA.Equipped with sensors facing the external and internal environments, AVs collect and store information about the bodily and mentally status of people in and around the vehicle, information about the vehicle itself, namely estimating energy consumption, locating the vehicle and other objects around it, and other information necessary for AI to operate the vehicle. Regulations protecting privacy should require prior consent for the collection and that the technologies associated with the collection phase minimize the amount of data collected. The processing phase provides AI categorized, tagged, and patterned sets of information to enable the usage phase. A standard regulation contains provisions on the limitation of the purpose of the processing of data, as well as the ability to modify data for the data subject; therefore, the regulation preserves privacy from threats such as data aggregation, identification, insecurity, secondary use, and exclusion. The collected and processed data enables AVs to anticipate incidents, make decisions, and improve upon them in the usage phase of the life cycle of information. To prevent AI from being biased, intrusive, and decisionally interfering, the regulation must grant the right to reject data usage to the data subject in addition to the purpose limitation requirements. In the last stage of the cycle, AV systems transmit data in networks or delete unnecessary data. The standard regulation grants data subject the right to control over the deletion of their collected data as well as requiring its consent for data dissemination to both maintain transparency and protect privacy against unconsented disclosures and breach of confidentiality.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Automated Technology, The Life Cycle of Information, Personal Data, Personal Information. -

Pages 717-737

There has long been debate over the definition of litigation among lawyers. One of the objections to this attempt was that it was useless or ineffective when each one was defined from a different perspective. We are now dealing with judgments in the courts in which the judge's decision is based on the definition of litigation and should not think that defining and analyzing concepts is completely useless. Sometimes the arbitrator or the court has to identify the meaning of the lawsuit in order to determine the possibility of hearing the lawsuit. Another result of defining a lawsuit and identifying its constituent elements is the effect it can have on the content of the judgment. In the sense that in order to be able to call the arbitrator's writing "award", I need to know the elements of "litigation". In the following, we will see that it is very important to identify the arbitrator's writing as an "award" and also that there is a fundamental connection between the litigation and the verdict in terms of their essential components. In the judicial and arbitration literature, the only issue that has been raised is what parts of the arbitration award are composed. We know that the arbitrator generally consists of three parts: introduction, cause of action, and direct meaning of text, but there is a more important question: What are the essential components of an arbitrator?Because the arbitrator's award is based on a lawsuit, the issue must be viewed from the perspective of the essential components of the lawsuit. Accordingly, the concepts related to the elements of the lawsuit form the conceptual framework of the discussion.To find the answer, the above question is submitted to several other questions: What are the elements of a lawsuit in arbitration? Should these elements be reflected in the arbitration award?Generally, every arbitration has its elements therefore the arbitral award is also issued based on the arbitration elements. This fact raises the question of whether the elements of arbitration should be reflected in the award. If we believe that the citation of arbitration element is necessary, another question comes to mind, as to what are the elements of arbitration? The hypothesis of this research is "arbitration as a mirror of lawsuit", according to which the expression of the elements of litigation in the arbitration is considered necessary and a sanction is considered for not expressing the elements of litigation in the arbitration. The research method here is descriptive-analytical.Accordingly, the question of what are the elements of arbitration should be answered. We believe that arbitrators have the liability to cite the elements of arbitration in the award. Consequently, the lack of element citation would lead to annulment or amendment of the award by an appeal. These elements are including parties, causes and the subject of the arbitration. Failure to mention the plaintiffs, if the award can be amended, should not lead to its annulment or non-recognition. However, not mentioning the subject of the arbitration is a case of annulment due to public order because the supervision on the already issued awards will be impossible for the court. Failure to cite the cause of the arbitration, as it results in the reasoning of the award, is also contrary to public order that result to the annulment of it.

Keywords: Elements of arbitration action, Elements of arbitration award, Sanction, Public Order, Award validity . -

Pages 739-761

Discussion about liability based on fault and the effect of fault in liability is an important topic in today’s law. However, given that the laws have not explicitly required the establishment of fault in causation, there are different views on what role to assign to the fault in tort judgments. Although damage, liability, causation and fault are favorite topics in fiqh (Islamic law) and extensive discussions are devoted to them, they do not convey an explicit position about the place of causality and they have not addressed the “what we are in” theoretically and have not given an independent topic to this issue. Thus both in fiqh and in Iranian law, there are serious uncertainties around the essential question whether any causality relation is enough for necessity of compensation or there should be an element of fault so that a ruling for compensation is issued. And if the latter view is accepted, where is the domain of fault? Despite what is sometimes said in fiqh, detailed reviews indicate that there is consensus among jurists that fault has no role in liability caused by direct loss (itlaf), and inflicting loss and causality are enough for liability. Therefore, it can be said that the domain of effect of fault in civil liability is limited to the indirect loss (tasbib). Islamic jurists, however, have conflicting views over indirect loss. Some have not required fault for liability in this category while majority of them, based on rules such as “the culprit is only liable for what he intended” and “there is no warranty in what is not considered harm by custom and even if it entails what is considered harm”, believe that in the event of indirect loss, the loss cannot be attributed to the agent and hence the liability doesn’t apply to him or her unless fault (even if in the objective sense) can be established. This view on indirect loss can be clearly understood from the writings of jurists such as Gazali, Allama Helli, and Al-Karraki. Thus whenever it is impossible to predict the loss to be resulted from an act so that rarely does that act lead to loss, that action is not subject to liability even if it leads to loss in the particular case. They believe that there is no evidence in the divine texts upholding that causation alone can bring about liability. Liability is, rather, but that accountability in causation is based on the coincidence of causality, the reasonable attributability of loss to the act, and about the establishment of the agent’s fault. In the Iranian law too due to lack of specification, lawyers have followed the same paths and there are two viewpoints among them. Some believe that in neither of direct and indirect losses, does the element of fault have any role and the realization of the three prongs of harmful action, loss and causation is enough for the compensation. This is while the majority of lawyers believe that the the motion for liability will be granted only when the fault exists in the committed act. In their opinion, the role and effect of fault in liability can be inferred not only from the articles 333 and 335 of the Civil Liability Act enumerating some variations of the indirect loss but from the articles 506 and 537 of the Islamic Penal Code. Hassan Emami supports this theory and believes that whoever damages other peopl’s properties will be liable only when he or she has either neglected the predictable results of his or her actions or has committed the act having thoseresults in mind. Given what was mentioned above, this article suggest that applying only one of the mentioned theories to the vast array of examples some of which are quite complicated and to diverse social and legal relations among humans is not reasonable and that a sound, principled approach would be to consult common usage and to use it as a criterion for proving or disproving the role of fault in liability caused by indirect loss.This study is carried out in an analytical-descriptive library method referencing original sources of fiqh and credible law books, and evaluates different viewpoints and their reasoning, examining the soundest among them more thoroughly.

Keywords: loss, Causation, Fault, Liability, Attributability -

Pages 763-782

The family has always been considered as the most basic social institution, paying attention to which is vital for ensuring the health of society’s members. Therefore, governments engage in systematic planning to support this institution, which contributes to the strength and consolidation of the whole society. Childbearing plays a very important role in the development of this social institution, improving the mental health of the family and thus of the community. Recent years have witnessed a special type of childbirth sometimes called calendar birth, in which parents insist, without being medically necessary, on untimely cesarean section to give birth to their child on a special day. This can have serious risks, because according to scientific research, interfering in the natural process of birth will have many negative and irreparable consequences. It is even acknowledged that important phases of fetal brain development take place in the final weeks of pregnancy. Families do this solely for the aim of bragging, and unfortunately it is going to form a new unfortunate, immoral custom. It should be noted that calendar birth is an issue in developed countries as well. It causes enormous costs to the health system of any country, as it deprives the baby of its uterine development, while the optimal growth and development of the fetus is a natural right of hers. Calendar childbirth is thus an emerging issue for discussion that have not been exclusively researched in Iran yet except for one article in which some dimensions of the legal responsibility ensuing from untimely cesarean operations have been examined with the emphasis being on the physician’s liability. The importance of addressing this issue is doubled by the threatening consequences that change the fate of innocent children, especially because this action is carried out by parents for non-therapeutic and unnecessary purposes. Civil liability has specific goals and functions with regard to the individuals directly involved, the wrongdoer and the victim, and to the society as well; therefore, identifying civil, criminal and disciplinary liabilities for those involved in the calendar birth can curb, to a great extent, the continuation of this abnormality.The present article has been written in a descriptive-analytical method using library studies and deductive reasoning, to address the concern thus described.Calendar birth is a cesarean section performed out of time without medical necessity, the sole purpose of which is to give birth to a baby on a specific date. This type of birth has inevitable risks for both mother and baby due to the change in the natural delivery process. Apart from being immoral, and seen from a legal viewpoint, the calendar birth imposes civil, criminal, and in some cases disciplinary liability on involved persons. Demonstrating the elements of civil liability, including 1) the entry of loss, 2) the harmful act and 3) the causal relationship, in calendar birth establishes the civil liability of physicians, parents and health centers. In such a birth, the doctor, having the knowledge and expertise, is the one to whom the untimely birth is directly imputable (direct agent or Mubashir), and the parents provide indirect cause (indirect agent or musabbib) by expressing their consent to the premature cesarean delivery. Health centers are potentially a third agent in possible damages, due to their role in employing the doctor and the health service contract they enter into with the parents.The present study seeks to answer the following questions: First, can civil liability be established in a calendar birth? Second, assuming the answer to the prior question is positive, who can be held liable for compensation? and third, what is the legal bases for such liability? There is definitely a case for civil liability, the article asserts, in the calendar birth, and doctors, parents, as well as medical centers can be held responsible. According to Article 526 of the Islamic Penal Code, in the case where both a direct and an indirect agent exist, the responsibility for compensation is distributed based on the effect of the perpetrators’ behavior and based on an objective standard. Therefore, the following results can be inferred:The calendar birth takes place with the aim of giving birth to a baby on a specific date or occasion, without considering the possible risks of untimely cesarean section. It is not only unethical, but also leads to legal liability.The elements of civil liability, i.e. the occurrence of loss, the harmful act and the causal relationship, can be established in the case of calendar birth for doctors, parents and health centers by deduction from various laws.The most recent policy the Iranian law adopted towards the case in which a direct agent and an indirect agent coexist is promulgated in Article 526 of the Islamic Penal Code enacted in 2013. This article explicitly holds the wrongdoer to whom the crime is imputable to be liable for compensation, and if the crime is imputable to all wrongdoers, they will each have an equal share of the liability, unless the effects of their behaviors in the loss are unequal, in which case their respective shares of responsibility will be proportioned to those effects, being measured according to an objective standard.The doctor, as a knowledgeable, expert professional involved in the calendar birth has the duty of providing adequate explanations to parents about the potential risks, and if cesarean section is performed, he will be held liable as the direct agent of the harmful act whose behavior have the greatest effect on the loss.Parents' consent to premature birth, when they are aware of the possibility of irreparable damages, is a cause of untimely cesarean section. Holding them responsible for their decision, which does have a tangible impact on the situation at issue here, as clearly endorsed by the objective standard, is in accordance with the law and with the interest of society and will help prevent the occurrence of similar incidents.The recognition of the principle of shared liability is Iranian law is attested in Articles 12 and 14 of the Civil Liability Act. The legislator has established a legal conception of causality in these articles, hence protecting the endangered rights in the best possible manner. Considering their employment relationship with physicians and their contract with parents, health centers also have to be held responsible to the extent of the impact of their behavior according to the objective standard.

Keywords: Coexistence of Direct, Indirect Causes in Tort, Physician, Calendar Birth, Civil Liability, parents, Health Centers . -

Pages 783-805

The right to non-performance is mentioned in Articles 377 and 378 of the Civil Code on the subject of sale, as well as in the section on marriage in Articles 1085 and 1086 of the same and in Article 371 of the Commercial Code. According to these articles, either party can refuse to fulfill its obligation in order to urge the other party to fulfill the latter’s obligation. The right to non-performance can be defined as the right of the parties to refuse to fulfill their obligation in order to oblige the other party to fulfill his obligation. This right, which is based on reciprocal justice and the common sense, has been accepted as one of the methods of compelling the fulfillment of contractual obligations in Imami fiqh and in civil law. Article 377 of the Civil Code gives each seller and buyer the right to refuse to surrender the item of sale and the price, respectively, until the other party agrees to surrender. According to this article, the creation of the right of non-performance for the parties to the contract is subject to the following conditions: a) the contract involves an exchange, that is, two mutual obligations; b) the two obligations are supposed to be fulfilled at the same time: this means that the right to non-performance exists either when bothobligations are to be fulfilled immediately once the contract is made or, and based on a broader interpretation of the relevant rules, when the two obligations are agreed to be done at the same time in future.But with regard to the scope of its application, there has been some dispute as to whether this right constitutes an exception to a general rule, hence having to be limited to the contract of sale and to the exchange of the item of sale and the price in it. This probability is supported, on the one hand, by the fact that the right to non-performance is mentioned in the Chapter on Sale, and on the other hand, by considering that, although the right to non-performance is possible in exchange contracts, the bond between the two obligations will be lost as a result of termination or cancellation of the contract and the returning of the objects of the two obligations does not stem from the contract itself, but is a general duty directly imposed by the rule that prohibits individuals from possessing other people’s property without the owner's permission. In addition, the termination of an exchange contract discontinues the mutual obligations of the parties, hence leaving no subject-matter for the right to non-performance, and the parties’ duty to return the items is not the result of the contract, but represents the obligation to give others’ properties back to them. A different view is that the right to non-performance is a general rule in exchange contracts, which is discussed, as is the general practice in the Islamic legal treatises, in chapters on sale as an example of a general rule. A third hypothesis is that the right to non-performance should not be limited to contracts and has to be applicable in all reciprocal obligations, even those imposed directly by law irrespective of the parties’ will. Therefore, this study seeks to answer the question whether the right to non-performance is applicable to all reciprocal obligations regardless of their source- contracts, tort liability or other rules. This descriptive-analytical study hypothesized that failure to recognize the right to non-performance at the stage of dissolution of the contract and other reciprocal obligations is contrary to the principle of the transactional justice and causes problems and unfair consequences when the items of the contracts are returned. Arguing that there is nothing that limits the right of non-performance in the stage of fulfillment of obligations, this article argues that this right exists not only in the stage of concluding contracts, but also in the stage where they are dissolved and the items are returned to their original owners, and also in mutual obligations arising from civil liability rules. The custom and the common sense does not warrant the differentiation between the stage of concluding a contract and its dissolution in both of which the parties are mutually committed to hand over the items to each other. The right to non-performance in the stage of dissolution of the contract exists according to the common implicit intention of the parties, whose authority is indisputably upheld by the custom especially the field of international trade, which gives it the same status as what is stipulated in the contract (Article 225 of the Civil Code). Thus, considering the need to study the principles of the right to non-performance and its conditions and obstacles, this article will first explore the concept of the right to non-performance and its bases and conditions in general and will then focus on the principles applying to, the conditions of exercising, and the effects of the right to non-performance in the stage of the dissolution of the contract and its mutual obligations.A review of the Islamic legal literature shows that the courts have accepted a broader interpretation of the scope of the right to non-performance. Some of the court decisions upholding the termination of the contract of sale have made the return of the sale item to the seller conditional on the refund of its price to the buyer. It should be noted that there are two conditions for exercising the right to non-performance in the stage of dissolution of the contracts: first, there must be two mutual obligations; second, they must have the same cause. The article will, thus, propose the scope of the right to non-performance in the Civil Code to be amended, and the right to non-performance to be recognized as a general rule applicable to the conclusion and termination of all obligations according to which in all exchange contracts, in both stages of conclusion and dissolution, as well as in all non-contractual mutual obligations which have to be performed simultaneously, each party can make the fulfillment of his obligation conditional on the fulfillment of the other's obligation.

Keywords: Right of non-performance, Return of exchanges, Reciprocity of exchanges, Exchange justice, Sale contract. -

Pages 807-826

World Trade Organization was founded with the purpose of freeing the trade between its members, in accordance with the principles of guaranteeing free trade among its members, the reduction of tariffs, the elimination of all forms of trade discrimination, and the transparency of trade laws and regulations. Nevertheless, the freedom of trade without any limits would concern the countries for their sovereignty and national security. Therefore, beside the general exceptions embodied in article 20, the article 21 of GATT was drafted under the title of security exceptions. This article reads as follows:“Nothing in this Agreement shall be construed:(a) to require any contracting party to furnish any information the disclosure of which it considers contrary to its essential security interests; or(b) to prevent any contracting party from taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests (i) relating to fissionable materials or the materials from which they are derived;(ii) relating to the traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and to such traffic in other goods and materials as is carried on directly or indirectly for the purpose of supplying a military establishment; (iii) taken in time of war or other emergency in international relations; or (c) to prevent any contracting party from taking any action in pursuance of its obligations under the United Nations Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security.” From the very beginning of the entry of GATT into force in 1947, until the foundation of WTO and thereafter, the interpretation of article 21 has been a subject of debate between the States and in the relevant literature. The main question in the interpretation of this article is to what extent the State-parties to GATT 1947 (and the members of WTO) have the freedom to invoke article 21, specifically, its paragraph (b). Can refraining by a State from its obligations by invoking this article be objected by other States or assessed by the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB)? We have suggested in this article that security exceptions are not specific to GATT and that several investment treaties, such as the Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations and Consular Rights between Iran and USA, also include similar exceptions. Nevertheless, in a general categorization, the security exceptions are drafted in two different methods. In the first, the language used for the security exception implies a degree of autonomy for States in recognizing security emergency and invoking it. The article 21 of GATT, as can be easily attested, falls in this category. Without using ancillary principles of interpretation, a reader could not reasonably assume any limit for the State’s discretion in invoking the security exception. The first method has thus been called the “self-judging” wording. In the second method, the language used in a treaty does not imply any self-judging property for the security exception. Article 20-1 of the Treaty of Amity between Iran and the USA has been drafted in this latter method. Through the negotiations of GATT in 1947, the security exception was inserted following a proposal from the USA. The history of drafting and resolution of this article shows that it has been found ambiguous from the outset of its drafting. At the 1947 and 1994 rounds, a number of different interpretations for article 21 have been presented. According to one interpretation, any State has full autonomy to recognize national emergency and to legitimately invoke article 21, and such autonomy cannot be objected by other States or assessed by the DSB. According to a second interpretation, although States have full autonomy to recognize national emergency, they shall observe good faith while invoking article 21. In accordance to a third interpretation, although States can themselves determine their security interests, the legitimacy of their invoking of article 21 can, without any boundaries, be retrospectively assessed by the DSB. The thesis proposed in this article is that the first interpretation is not acceptable as the State-parties cannot have limitless freedom to invoke article 21 and that the legitimacy of invoking this article can be assessed by the DSB by considering objective standards, such as good faith. The DSB itself acknowledged the same approach in Russia- Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit. In this case, the panel primarily considered whether it has the jurisdiction to qualify the legitimacy of invoking article 21by Russia. The panel reasoned that since the article 21(b) enumerates a limited number of scenarios, the members can only invoke that paragraph in the event one of those scenarios occur. In addition, the panel found that the emergency circumstances are objective in nature. This objectivity confers the panel to assess the legitimacy of invoking paragraph (b). Since the resources for this study include essays, books and the awards rendered by the DSB, this article first briefly reviews the sources using library research and,then, using descriptive analytic method, attempts to examine the core of the controversy, explore the history of its emergence and evolution, and evaluate the contending readings involved, analyzing both the views submitted in the literature and the positions adopted practically by the States and the DSB.

Keywords: Article XXI of GATT, Principle of Good Faith, Security Exception, World Trade Organization, Panel.