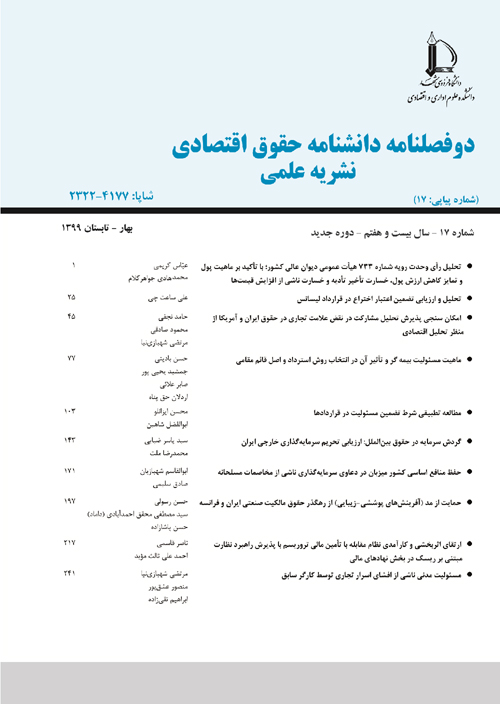

فهرست مطالب

دانشنامه حقوق اقتصادی

سال بیست و هفتم شماره 1 (پیاپی 17، بهار و تابستان 1399)

- تاریخ انتشار: 1399/11/05

- تعداد عناوین: 10

-

-

صفحات 1-24

در این مقاله، رای وحدت رویه شماره 733 هیات عمومی دیوان عالی کشور، با روش توصیفی تحلیلی و با هدف تعیین خسارت قابل جبران در فرض مستحق للغیر درآمدن مبیع، تحلیل شده است. ظاهر رای نشان می دهد که تنها کاهش ارزش پول بر مبنای نرخ تورم قابل جبران بوده و خسارت ناشی از افزایش قیمت ها از شمول رای خارج است؛ این در حالی است که اختلاف شعب دادگاه های تجدیدنظر استان آذربایجان غربی، امکان جبران خسارت ناشی از افزایش قیمت ها بوده است. نظریه مشورتی اداره حقوقی قوه قضاییه مورخ 19/2/1394 نیز کاهش ارزش پول را براساس ماده 522 ق.آ.د.م. و بر مبنای شاخص بانک مرکزی قابل جبران دانسته است. بر این اساس، بایع فضولی باید کاهش ارزش پول (ثمن) را بدون آنکه نیازمند مطالبه باشد، بر مبنای نرخ تورم به خریدار بپردازد؛ ولی جبران خسارات ناشی از افزایش قیمت ها تابع قواعد عمومی ضمان قهری و ماده 391 ق.م. است و فروشنده فضولی باید تفاوت ثمن و قیمت روز مبیع از باب عدم النفع مسلم جبران کند. از حیث میزان خسارت قابل جبران نیز بایع اصولا باید تفاوت ثمن با قیمت روز «امثال مبیع» را در زمان تادیه، پرداخت کند؛ اما پیش بینی های متعارف افراد و شرایط ویژه مبیع نیز باید لحاظ شود.

کلیدواژگان: رای وحدت رویه شماره 733 دیوان عالی کشور، کاهش ارزش پول، خسارت ناشی از افزایش قیمت ها، ربا، خسارت تاخیر تادیه، عدم النفع -

صفحات 25-44

در پژوهش حاضر یکی از مسایل مهم حقوق قراردادی در حوزه مالکیت صنعتی مورد بررسی واقع شده است. پرسش مهمی که وجود دارد آن است که در قرارداد لیسانس اختراع آیا لیسانس دهنده، تعهدی در خصوص تضمین اعتبار اختراع دارد؟ در پاسخ به سوال طرح شده، اکثریت دکترین حوزه مالکیت فکری بر این دیدگاه است که وجود چنین تعهدی در قرارداد لیسانس ناممکن است. در این راستا برخی از دکترین داخلی، امکان وجود تضمین اعتبار اختراع را به طور کلی غیرممکن دانسته و مشهور دکترین خارجی با دلایلی چون عدم معقولیت؛ وجود دکترین تغییرات در حوزه اختراعات و همچنین به جهت ماهیت قرارداد لیسانس، احراز چنین تعهدی در قرارداد لیسانس را ناممکن می دانند. با وجود این، بررسی ها نشان می دهد دلایل مورد استناد در خصوص نفی کلی وجود چنین تعهدی، صحیح نبوده و همچون دیدگاه غالب نویسندگان در حوزه مالکیت فکری، اصل تعهد صحیح به نظر می رسد. اما در رابطه با دلایل مربوط به عدم احراز چنین تعهدی در قرارداد لیسانس اختراع، لازم است میان شروط اعتبار اختراع، قایل به تفکیک بود به این صورت که تضمین اعتبار اخراع از حیث جدید بودن آن با توجه به آن که تمامی منابع علمی موجود در اختیار نیست اصولا ممکن نبوده و در مقابل؛ تضمین اعتبار از حیث کاربرد صنعتی وگام ابتکاری در پاره ای از موارد به طور ضمنی قابل احراز می باشد.

کلیدواژگان: عدم معقولیت، دکترین تغییرات، قالب قراردادی، شروط ماهوی اختراع، تضمین اعتبار -

صفحات 45-76

در حقوق آمریکا، نقض علامت تجاری به دو طریق واقع می شود؛ مستقیم و غیر مستقیم. در نقض غیر مستقیم، شخص بدون ارتکاب عملی که مشمول نقض علامت تجاری شود، رفتاری را انجام می دهد یا در وضعیتی قرار می گیرد که حسب مورد، مسبب نقض مشارکتی (و انگیزشی) یا نیابتی می گردد. علامت تجاری، جزو نوآوری های غیر فناورانه است و توسعه ی حمایت از آن به طور مستقیم به افزایش میزان بهره وری اقتصادی منتهی نمی گردد. افزایش حمایت از علایم تجاری در قالب توسعه ی مسئولیت ناشی از نقض آن، در صورتی مطلوب است که نوآوری فناورانه در وضعیت بهینه ای قرار داشته باشد. با عنایت به وضعیت مطلوب نوآوری فناورانه در آمریکا، شناسایی چنین نهادی موجه به نظر می رسد. در مقابل، در نظام حقوقی ایران، مسئولیت غیر مستقیم ناشی از نقض علامت تجاری پیش بینی نشده و مصادیق مختلف این نوع نقض، مشمول مقررات عام مسئولیت مدنی بوده که این امر با عنایت به وضعیت کمتر مطلوب نوآوری فناورانه در ایران از وجه منطقی برخوردار است. هدف از تحقیق حاضر، با استفاده از روش توصیفی- تحلیلی و تحلیل اقتصادی شامل اثباتی و هنجاری، بررسی مسئولیت نقض غیر مستقیم علامت تجاری از منظر آثار آن در حوزه ی فناوری است. وضعیت آمریکا به لحاظ فناوری، شناسایی و اعمال چنین مسئولیتی را با توجه به ارکان آن، موجه جلوه می کند اما با عنایت به وضعیت نوآوری فناورانه در ایران و با لحاظ جمیع شرایط از جمله، مقررات بین المللی، وضعیت سیاسی- اقتصادی ایران در عرصه ی بین المللی، عدم شناسایی نهاد مسئولیت غیر مستقیم ناشی از نقض علامت تجاری و اتکا به مقرات عمومی مسئولیت مدنی در این زمنیه، توجیه شده و توصیه می گردد.

کلیدواژگان: نقض غیر مستقیم، علامت تجاری، برند، فناوری، حقوق ایران، حقوق آمریکا -

صفحات 77-102

یکی از ابهامات موجود در عقد بیمه چیستی و ماهیت مسئولیت بیمه گر در عقد بیمه است. بدین معنا که پرداختی بیمه گر، دارای ماهیت «طلب» بیمه گذار است یا «خسارت» واقعی؟ و کشف این ماهیت چه تاثیری در توجیه مبنای«اصل قایم مقامی» و انتخاب روش «استرداد» در چگونگی اعمال همزمان نظامهای پرداخت دارد؟ ماهیت مسئولیت و پرداختی بیمه گر به بیمه گذار حتی در بیمه هایی که پرداخت تابع اصل جبران خسارت است، ماهیت طلب و عوض قراردادی دارد و حق مراجعه به عامل زیان از باب خسارت برای بیمه گذار (بوسیله قایم مقام قانونی وی یعنی بیمه گر) وجود دارد. اگر ماهیت جبران در بیمه، خسارت فرض شود و رجوع به عامل زیان مشمول قاعده «منع جبران مضاعف» شود، چنین حقی برای قایم مقام وی(بیمه گر) نیز متصور نخواهد بود زیرا با جبران از سوی بیمه گر، خسارت زیاندیده جبران شده و دیگر نمی توان (اصالتا یا وکالتا) به عامل زیان رجوع نمود، به عبارت دیگر «طلب» دانستن ماهیت پرداختی بیمه گر لازمه توجیه «اصل قایم مقامی» و نظام «استرداد» است. مبنای انتخاب نظام «استرداد» و وجود اصل قایم مقامی را باید در مبنای «قانونی- قراردادی» مسئولیت در بیمه و نظام «تضمین گروهی» و «سیاست توزیع ضرر» جستجو کرد.

کلیدواژگان: قائم مقامی، بیمه گذار، بیمه گر، خسارت، روش استرداد -

صفحات 103-142

شرط تضمین مسئولیت از اقسام شروط ناظر به مسئولیت و از ابزارهای تخصیص ریسک اقتصادی است که به ویژه در قراردادهای حوزه نفت و گاز استفاده می شود. این نهاد از منظر اقتصادی کارکرد پارتویی دارد و بار ریسک اقتصادی را برعهده ی طرفی قرار می دهد که معمولا توانایی بیشتری برای تحمل خسارت دارد. درباره ی مفهوم این نهاد در نظام کامن لا و همینطور در حوزه ی قراردادهای تجاری بین المللی ابهاماتی است که در حقوق ایران نیز می تواند محل بحث باشد. همچنین وجود نهادهای مشابه به ابهامات موجود درخصوص این نهاد دامن زده و استفاده صحیح از آن را پیچیده ساخته است. درخصوص اعتبار این نهاد نیز تردیدهایی با محوریت نظم عمومی مطرح شده که اگرچه اصل اعتبار آن را مخدوش نساخته، اما سبب طرح موانعی برای نفوذ آن شده است. درنهایت، آثار این شرط نیز مجرای مسایل حقوقی دقیقی است که ملاحظه ی برخی آرای متشتت صادره از دادگاه های ایران، ضرورت بررسی آن را آشکار می سازد. هدف این مقاله، زدودن برخی نکات مبهم پیرامون مفهوم این شرط، در کنار بررسی اعتبار و واکاوی آثار آن است. بدین منظور، با روشی توصیفی-تحلیلی در ابتدا به مفهوم شناسی این نهاد پرداخته شده است؛ سپس اعتبار این تاسیس حقوقی مطالعه شده و در نهایت آثار آن بررسی گردیده است.

کلیدواژگان: بیمه مسئولیت، حق جبران غرامت، تخصیص ریسک اقتصادی، شرط تضمین جبران خسارت، شرط جایگزینی مسئولیت -

صفحات 143-170

جریان آزاد سرمایه در راستای آزادسازی تجارت جهانی مورد توجه اقتصاددانان بوده است. صندوق بین المللی پول، سازمان تجارت جهانی، اتحادیه اروپا، سازمان همکاری اقتصادی و توسعه، گروه بیست، موافقت نامه های تجارت آزاد و معاهدات دوجانبه سرمایه گذاری خارجی بر این اصل تاکید داشته اند. استثنایاتی نیز بر جریان آزاد سرمایه وارد شده است که باید مضیق و محدود اعمال شود. این محدودیت ها شامل فقدان زیرساخت های اقتصادی، فقدان تراز پرداخت ها، وجود مشکلات مالی خارجی، مغایر بودن با نظم و منافع عمومی جامعه و بحران های اقتصادی و مالی است. مقاله حاضر به دنبال پاسخ به این سوال است که تحریم سرمایه گذاری خارجی ایران در پرتوی مقررات مربوط به گردش آزاد سرمایه در حقوق بین الملل چگونه تحلیل می شود؟ تحلیل مورد نظر با روش توصیفی-تحلیلی در چهار بخش شامل تحدید و گردش آزاد سرمایه در اقتصاد بین الملل، تحدید و گردش آزاد سرمایه در حقوق بین الملل، سرمایه گذاری خارجی در حقوق بین الملل: از تشویق تا تحریم و ارزیابی تحریم سرمایه گذاری خارجی ایران صورت گرفته است. در نهایت این نتیجه حاصل گردید که ورود و خروج سرمایه یا ارز به دولت ها به نحو ارادی و غیرارادی صورت می پذیرد. در این میان تحدید ارادی ورود سرمایه و تحدید ارادی خروج خاص سرمایه می تواند مغایر با برخی تعهدات حقوق بین الملل باشد. تحدید ارادی خروج سرمایه به یک کشور خاص همان تحریم سرمایه گذاری خارجی دولت است که مغایر با برخی تعهدات بین المللی است. تحریم سرمایه گذاری خارجی ایران با هیچ یک از استثنایات مذکور در اسناد بین المللی مطابقت ندارد و نیز مغایر با تعهدات ناشی از معاهدات دوجانبه سرمایه گذاری خارجی، موافقت نامه مودت و برنامه جامع اقدام مشترک (برجام) است.

کلیدواژگان: تحریم، سرمایه گذاری خارجی، گردش آزاد سرمایه، جریان آزاد سرمایه، جمهوری اسلامی ایران -

صفحات 171-196

با توجه به افزایش مخاصمات مسلحانه، تعداد کشورهای میزبان سرمایه گذاری که توسط سرمایه گذاران آسیب دیده به داوری فراخوانده می شوند بسیار افزایش یافته است. استناد اغلب این سرمایه گذاران به استاندارد حمایت و امنیت کامل مندرج در معاهده دوجانبه سرمایه گذاری میان کشور متبوع خود و کشور میزبان سرمایه گذاری است. از آنجا که اغلب معاهدات به روشنی ماهیت و قلمرو این استاندارد را مشخص ننموده اند، دیوان های داوری به اختیار خود به تفسیر آن پرداخته و در مواردی با ترجیح منافع سرمایه گذار بر منافع دولت میزبان بدون توجه به شرایط خاص موجود در مخاصمات، اقدام به صدور رای نموده اند. این مقاله با اتخاذ روش توصیفی-تحلیلی می کوشد تا با مراجعه به رویه داوری و معاهدات سرمایه گذاری به منظور حمایت از منافع دولت میزبان به شفاف سازی ماهیت و قلمرو استاندارد حمایت و امنیت کامل در شرایط مخاصمات مسلحانه بپردازد. واقعیت آن است که دولت میزبان تنها ملزم به رعایت همان تعهداتی است که صراحتا در متن معاهده سرمایه گذاری پذیرفته است و دیوان های داوری در ارزیابی رعایت این تعهدات باید به شرایط، امکانات و منابع هر کشور به صورت موردی توجه نمایند و قلمرو تعهدات دولت میزبان را با اعمال تفاسیر موسع از این تعهدات افزایش ندهند.

کلیدواژگان: داوری سرمایه گذاری، مخاصمات مسلحانه، معاهدات سرمایه گذاری خارجی، منافع دولت میزبان -

صفحات 197-216

با گسترش مفهوم و مصادیق صنعت، آموزه ها و دکترین حقوق آفرینش های مرتبط با مد نیز به مثابه یکی از مهم ترین جلوه های حقوق مالکیت فکری، توسعه پیدا کرده و حمایت از آن، تا حد قابل توجهی در دو نظام حقوقی ایران وبه ویژه در حقوق فرانسه مورد توجه قرار گرفته است. آفرینش های مرتبط با مد، صرف نظر از مفهوم و مصادیق گسترده و متنوع خود، از بعد حقوق مالکیت صنعتی، در حقوق فرانسه همچنان که در نوشتارهای حقوقی مرتبط با این موضوع آمده، در چارچوب مصادیق مختلفی از جمله حقوق ناظر بر طرح ها و مدل ها، حق اختراع، طرح صنعتی، اسرار تجاری، علامت تجاری و...قابل حمایت بوده و مقررات هریک از موارد مذکور، نسبت به آن قابل اعمال خواهد بود. در حقوق ایران نیز، به رغم آنکه چه در بعد تقنین و چه در بعد تفسیر این بحث در تالیفات حقوقی، به مانند حقوق فرانسه چندان سخنی به میان نیامده است، با این حال، با استقرای در آموزه های حقوق مالکیت صنعتی فرانسه و مقایسه آن با حقوق ایران و با لحاظ معیار اسلامی - ایرانی امر مزبور و هم چنین، تطبیق قواعد ناظر بر هریک از مصادیق مالکیت صنعتی در رابطه با این موضوع، یافته های این پژوهش نشان گر آن است که می توان مصادیق متعددی به منظور حمایت از مد از جمله حق اختراع، طرح صنعتی، نشانه های جغرافیایی، علامت تجاری و اسرار تجاری را بر آن منطبق ساخت.

کلیدواژگان: حقوق مالکیت صنعتی، مد، حق اختراع، طرح صنعتی -

صفحات 217-240

نظارت بر نهادهای مالی به ویژه بانک ها از حیث اجرای قوانین و مقررات مقابله با تامین مالی تروریسم یکی از مهمترین موضوعاتی است که اسناد بین المللی بر آن تاکید نموده اند و کشورها باید در جهت ارتقای اثربخشی و کارآمدی نظام مربوط به آن تلاش کنند. سازمان ها، موسسات و گروه های بین المللی، راهبرد مدیریت ریسک را جهت افزایش اثربخشی و کارآمدی نظام مقابله با تامین مالی تروریسم پیشنهاد کرده اند. اعمال این راهبرد مستلزم ایجاد مبانی حقوقی و به کار بستن تدابیر اجرایی است؛ بنابراین هدف این پژوهش از یک طرف، امکان سنجی اجرای راهبرد نظارت مبتنی بر ریسک در پرتو مبانی قانونی مورد پذیرش در سیاست جنایی تقنینی ایران است و از طرف دیگر سنجش میزان اثربخشی و کارآمدی سیاست جنایی اجرایی جمهوری اسلامی ایران در قبال مقابله با تامین مالی تروریسم در حوزه نظارت بر نهادهای مالی بوده که با روش توصیفی در جهت تحقق آن تلاش شده است. این پژوهش نشان می دهد که نظارت مبتنی بر ریسک بر نهاد مالی از حیث رعایت مقررات مبارزه با تامین مالی تروریسم در سیاست جنایی جمهوری اسلامی ایران از جایگاه مطلوبی برخوردار نیست؛ زیرا در حوزه تقنین، مبانی قانونی لازم پیش بینی نشده و در حوزه اجرا نیز علیرغم تلاش های صورت گرفته، تدابیر اجرایی کافی به کار گرفته نشده است.

کلیدواژگان: نظارت مبتنی بر ریسک، نظارت، مقابله با تامین مالی تروریسم، سیاست جنایی -

صفحات 241-261

اسرار تجاری دارای ارزش اقتصادی بوده و در دسترس عموم قرار ندارد و تلاش های معقولانه ای در حفظ و حراست از محرمانگی آن انجام می گیرد. افشای اسرار تجاری در سطح محدود و برای هدف مشخص به کارگران جهت انجام تکالیف کارگری موجب از بین رفتن مالیت و محرمانگی آن نمی شود، به طوری که کارگران در زمان وجود رابطه استخدامی و بعدازآن ملتزم به رازداری می باشند. با این وجود در مواردی بعد از اتمام رابطه استخدامی کارگر سابق سبب افشای اسرار تجاری مربوط به رابطه استخدامی سابق می شود. این پژوهش با شناخت مفهوم و ماهیت اسرار تجاری و افشای موجب ضمان، با استفاده از روش توصیفی - تحلیلی و ابزار کتابخانه ای، مسئولیت مدنی ناشی از افشای اسرار تجاری توسط کارگر سابق را موردبررسی قرارداده است. نتیجه ی حاصل از این پژوهش نشان می دهد که اسرار تجاری مال بوده و ید کارگر سابق نسبت به اسرار تجاری امانت قانونی است مگر اینکه انکار کرده یا اقدام به افشای اسرار تجاری نماید که در این صورت با مبانی تعیین مسیول ازجمله غصب، اتلاف، دارا شدن بلاسبب و غرور، مسیول جبران خسارت، نحوه توزیع مسئولیت و مبنای مسئولیت مدنی در این حوزه قابل تعیین و بررسی است.

کلیدواژگان: مسئولیت مدنی، اسرار تجاری، کارگر سابق، کارفرما، افشاء

-

Pages 1-24Introduction

Due to the high rate of inflation in Iran, which itself is caused by various factors, our legal system and judicial procedure has faced the problem of devaluation of money and how to compensate it for many years. To solve this problem, the legislator has limited and incomplete solutions in Article 522. In order to compensate for the decrease in the value of money and Article 1082 BC. It has provided for the adjustment of Rail dowries. In particular, in the case where the sale is void due to the merits of the seller and the non-enforceability of the owner and the seller of the invoice must return the price to the buyer, how the seller undertakes to reject the price due to devaluation has always been a matter of debate. This problem becomes more acute when a few years have passed since the transaction and then it is discovered that the seller belongs to another and the owner of the transaction does not enforce it. In this case, the purchasing power of money and its value has decreased due to high inflation and the return of the same nominal value seems unfair. In particular, the buyer is deprived of the minimum interest of his money which is in the possession of the prying seller and he has benefited from it, because if the customer had invested his price in the bank, he would at least receive the profit from his participation at the rate of inflation rate, and it is possible that the profit on account of the participation would be more than the inflation rate. In addition, due to rising prices, the buyer will have to pay a much higher price to buy similar financial goods, and therefore, the idea of compensation is necessary. The vote of procedure No. 733 of the Supreme Court seeks to resolve these issues; But it itself adds to the doubts and ambiguities and has many shortcomings and flaws.

MethodologyIn the present study, descriptive and analytical research methods have been used and the method of collecting information and data is library. Also, the issue has been analyzed from a jurisprudential, legal and judicial point of view.

Results & DiscussionPaper currencies are of a special nature today and, unlike gold and silver, are of no intrinsic value; they are only of credit value, and the banknote is the only representative of money. Therefore, the value of today's money is its purchasing power and its exchange power. According to this analysis, the debtor's debtor must return to the creditor the value equivalent of what he has received in order to fulfill his obligation, and the mere reimbursement of its nominal value, if the purchasing power of money has decreased, does not absolve him of liability. So, what he owes in addition to the nominal value of money in terms of inflation is not an excess of his debt, but the fulfillment of the principle of his commitment, the value of which is diminished and compensated for by an amount equal to the rate of inflation. Accordingly, the devaluation of the currency differs from that of usury, as well as the damages for late payment, and its compensation must be accepted as a general rule.

Conclusion and SuggestionsAccording to the provisions of the vote of Procedure No. 733 of the Supreme Court, the prying seller should simply return the price in terms of "devaluation" and is not responsible for the increase in property prices. The General Legal Department of the Judiciary also commented in 2015 that the devaluation of the price in the vote of procedure No. 733 is calculated based on the Central Bank's index. This is while was predicted compensating for the devaluation of money as a general rule, before the vote of procedure in Article 522. The only advantage of the Unity of Procedure vote is that the conditions set out in Article 522 are not necessary to compensate for the devaluation of the price. Of course, this innovation is not very noticeable, because the volatile bond must return the price according to the rule of iodine guarantee, and the condition of the claim stipulated in the mentioned article about the reduction of the value of the price is automatically eliminated. In addition, "damages resulting from price increases", which were the main differences between Branches 3 and 11 of the Court of Appeals of West Azerbaijan Province, in the unanimous decision of the procedure has been compensated for the reduction of money laundering and thus, demanding price differences and daily prices. The prying scales are out of the scope of the vote. Therefore, in order to compensate for the difference between the contractual price in terms of inflation rate and the current day price, the general rules of coercive guarantee and Article 391 BC must be applied to the general rules. It turns out that the existing rules make the said damage compensable, because the buyer is deprived of having a seller by the invalidity of the sale, and this is a certain benefit to the detriment of custom, and therefore, the loss agent must compensate the said loss. The criterion for calculating the amount of compensable loss is basically the same, that is, the difference between the price and the price of the day should be calculated and paid according to the seller; however, conventional predictions of individuals and special conditions of the seller must also be considered. Therefore, it is suggested that the legislature of Article 522. Corrects and considers the devaluation of money as absolute and even without the conditions stipulated in this article. Also, the judicial procedure considers the damages caused by the increase in prices to be compensable based on the findings of the present research.

Keywords: judicial precedent No. 733, Devaluation of the Money, Damage for Raise of Price, Usury, Damage for delay in payment, Loss of Prospective Profits -

Pages 25-44Introduction

According to Article 2 of the Patent, Industrial Designs, and Trademarks Act, the intended knowledge has legal credit and, consequently, legal protection. The knowledge will have three conditions: 1- must be new 2- must be innovative and 3- must have industrial applicability, namely, has a validity certificate and being in right of priority stage and their patent application was filed before legal authorities. However, from a contractual point of view, the mere validity of the intellectual property at the time of the contract is not sufficient as the exploitation of the invention depends on its subsistence. It is, therefore, necessary to distinguish between "original credit" and "subsistence" because the patent is only a criterion for evidence of its validity. The patent may be invalidated after the registration for various reasons. Therefore, because the subsistence is necessary for the exploitation of intellectual property, and since the preliminary validity of the invention is also costly, it is necessary to warranty the validity appropriately. It should also be noted that due to this feature (the revocation whenever possible) in the patent law system, it is less considered in terms of the insurance. It may be due to the weakness of the patent system in the scope of patents and occurring frequent violations as well. To this end, the present research seeks to answer the fundamental question of whether in the patent license, there is a warranty or commitment from the licensor for the validity of the invention. Theoretical framework In the present article, the concept of Warranty of validity is compared with other similar concepts at first and then the arguments of pros and cons about the existence of a Warranty of validity in the license agreement are examined. At first, the impossibility of Warranty of validity and then the reasons for not recognizing such a warranty in the license agreement are examined.

MethodologyThe research method in this article is descriptive-analytical in the sense that concerning the topic mentioned above, firstly, the existing views and critiques will be examined and finally, a concluded theory will be presented.

Results and discussionRegarding the analysis and evaluation of the credit warranty in the patent license, it has become clear that the authors suggest two significant reasons in opposition to the credit. First, the reason for denial of the structural existence of such a warranty, and in the second argument, the validity of the license agreement is denied. The examination of the reasons mentioned above showed that the obligation to warranty is entirely correct and does not face any severe problems by contractual rules. However, concerning the patent validation warranty, there are three main reasons for rejecting a warranty: 1- the lack of rationality in the second license. 2- the negation of the warranty following the doctrine of modification. 3-the lack of warranty due to the license. Nevertheless, examination of the reasons mentioned above shows that such a warranty in the license agreement is not only unreasonable but may be fulfilled in some cases, but regarding the doctrine of changes in the field of invention, it should be noted that its explanation requires recognition of subject matter of the license agreement distinguishing it from goods and, ultimately, the denial of contractual form warranty. Although, in some cases, it may be following the current customs of license agreements, in cases where the License contains monopoly conditions, there is a higher degree of warranty of validity. In other words, it depends on the type of reading that exists in the license agreement and cannot believe in absolutely non-credibility.

Conclusions & SuggestionsRegarding the arguments described above, a supportive view of credit warranty in the license agreement is distinguishing between the different conditions of credit. Whereas there is no access to all scientific resources; the attribution of the novelty of an invention, beyond the licensing knowledge, is contrary to contractual expectations and mutual agreement, but about other patent conditions (industrial use and innovative step) Because it is at the discretion of the licensor, the commitment to warranty and attributing to the latter person seems correct. However, in case of disagreement between the parties in the exclusive license, the existence of warranty is a principle and the licensor shall prove non-warranty of credit, but in the non-exclusive license, non-warranty of credit shall be proved by the licensee.

Keywords: Warranty of validity, unreasonably, Quirkiness of patent doctrine, Contractual frame, Substantial conditions of innovation -

Pages 45-76Introduction

Indirect liability in US, is creation of US case law and plays an important role in the functioning of the trademark system, in order not to mislead the consumer and reduce his search costs, as well as expanded protection of trademark rights. Given the US trade-economic and technological situation, this practice seems justified, which can well guarantee the US commercial and economic interests, not only in the domestic system, but also in the international trade. Innovation is the foundation of sustainable economic development in the age of knowledge-based economy and technological innovation, play a major role. However, the role of non-technological innovation, including trademarks, in economic growth and development has been considered. However, this role is still secondary and complementary, and it is technological innovation that Determines the power of competitiveness of companies and governments in domestic and international trade. The us is a country that has a privileged position in the world in terms of trade and economy, and this privileged position, without a doubt, depends on its position in the field of technological innovation. Technological innovation has boosted the country's export growth and, consequently, its economic growth by improving its competitiveness. Obviously, in such a situation, strengthening the non-technological innovation system will strengthen the position of technology and will be very effective in protecting the rights of technology owners. With this analysis, regardless of the legal basis of indirect liability for trademark infringement, the recognition of such liability is in line with the US trade-economic and technological situation and can better guarantee and protect its benefits in international trade relations. In contrast, Iranian economic and social system is less desirable than the US in terms of technological innovation. Therefore, the identification of such an institution is not recommended in it and it seems that at least based on the situation of innovation production in Iran and exports in this field, not identifying a similar institution has a logical aspect. On the other hand, the common cases of indirect liability arising from participation in trademark infringement in Iranian law, are subject to the rules governing the determining the liable person under the rule of the combination causes in loss. The application of these rules, such as the rule of liability that takes precedence over the effect, entails the permanent liability of the direct infringer, because at first, his act is effective in infringing the trademark.

Theoretical frame workParticipation in trademark infringement, is the facilitation or encouragement of trademark infringement without committing the actus reus of trademark infringement. Sometimes, this partnership is proven by not supervising the direct infringing act, in addition to gaining financial benefit from the infringement of the mark, the latter type is called vicarous infringement and the first case is called contributory infringement. Identifying this type of liability expand trademark rights. In terms of economic analysis, broader brand protection leads to productivity if technology is at a high level , because consumers become loyal to higher-tech brands. The relationship between a sense of loyalty to the brand and the technology of the products, makes the rules of indirect trademark infringement in the US described as favorable, and in contrast, due to the low technology of Iranian products in the market compared to US products, lack of explicit identification of Trademark infringement in Iran, seems optimal.

Methodology Researchdata were collected using the library method. Physical and ebooks and articles are the main sources of data for this research. After collecting data in this way, the present study, with an analytical-descriptive method, first examines Concepts about participation in trademark infringement, such as contributory and vicarious infringement, are examined. Then, the principles and foundations of each of these two types of infringement in the US legal system are explained, and then the issue is examined from the perspective of economic analysis. Finally, the legal and economic situation of Iran in relation to the issue of participation in trademark infringement is analyzed.

Results & Discussioncases and principles of contributory and vicarious infringement in US are consistent with the business, economic, and technological situation in this country; Technological innovation is in a favorable situation, and for this reason, in accordance with such a situation, the elements ofcontributory and vicarious infringement, have been defined. There is no similar theory in Iranian law and considering the commercial, economic and technological situation in Iran, identifying a similar theory is not recommended.

Conclusions & SuggestionsThe degree of technological development of countries and their political, commercial and economic conditions, especially at the level of international interactions, play a pivotal role in determining the legal policies of countries. Legal regulations are a tool at the disposal of countries to use them to pursue their goals. Accordingly, just as a single intellectual property rights framework is not appropriate for all aspects of this legal system, a single framework cannot be the criterion for action by all countries. The institution of indirect trademark liability has two different outcomes and functions in the two legal and economic systems of Iran and the US; In the US, due to the high level of technological innovation and its superior competitiveness domestically, it leads to the development of legitimate trade competition, and at the level of international interactions, it will increase the country's economic growth through the development of technological innovations. Conversely, recognizing this in Iran will reduce new businesses and legitimate activities domestically, and in the international arena will lead to currency outflows and difficulty in technological innovation due to the transfer of liability risk to legitimate commercial activities and the imposition of foreign trademark management costs on domestic industries.Therefore, the lack of identification of the institution of indirect trademark infringement in Iran and reliance on the general rules of civil liability in this regard, is considered sufficient and especially in the context of scientific and technological sanctions on Iran, it seems more desirable.

Keywords: trademark, contributing in infringement, economic groth -

Pages 77-102Introduction

One of the ambiguities existing in the insurance contract is the quiddity and nature of the insurer's liability in the insurance contract, which means whether insurer's payments is of the nature of a demand insured or real damage. The nature of the insurer's liability has a direct effect on the possibility of insured's referring to the tortfeasor and on the possibility of accumulating the damage imposer’s liability and insurer's liability (due to differences in origin). In this way, if the nature of the payments that the insurance company pays to the insured or the stakeholder is a credit (or savings or replacement of the contract), the injured party (the insured), after obtaining the insurance money from the insurer pursuant to contract, can refer to the tortfeasor because of the difference in the origin of liability (contractual and forcible) and the responsible person (insurance company and tortfeasor).

Theoretical frame work, Methodology, Results & DiscussionThere are several legal systems to compensate for the insured’s losses, the most important of which include: 1. Selection: This means that the damaged party can refer to one of the responsible agents (insurer or tortfeasor) at his/her own selection. 2. Accumulation of benefits: This system is operative according to the principle of capital and, thereby, the damaged insured can also refer to the contractual legal system in addition to entitlement to refer to the forcible liability. 3. Recoupment: The contractual liability (insurer) can refer to the forcible liability after the loss and damage was compensated for and demand the tortfeasor for compensation for the payment already incurred. 4. Relieving the Tortfeasor’s liability: This means that neither of the parties are entitled to refer to the tortfeasor (Cane, 2006: 377; Lewis, 1998: 17). The principle of subrogation, which has been approved by Iranian legislatures, is a subset of the recoupment system and entails the fact that the insurer should refer to the tortfeasor while the damage was compensated for and amount paid to the insured should be claimed for refund from the tortfeasor. In domestic law, the principle of subrogation is viewed to be based on the rule of "double compensation prohibition " and "prohibition of unjust ownership" and is interpreted on the basis of recognizing the insurer's payment to the insured as "damages". In other words, when the insurer compensates for the insured's loss by paying for the damages, the insured can no longer refer to the insurer because one of the pillars of the claim is the civil liability of damages survival. Thus, when the insured's damages were paid by the insurer, the insured does not have the right to refer to the tortfeasor but the insurer can refer to the tortfeasor on behalf of him/her (Babaee, 2005: 25; Taheri, 2008: 22). In this research, for the following reasons, it was proved that the nature of the insurer's payment has been a "credit" and the above argument is not correct. First, according to Article 1 of the Insurance Law in 1937, insurance is a commutative contract and the insurer's indemnity is paid for the insurance premiums paid by the insured. In addition, the insurer's obligation originates from the insurance contract; therefore, the nature of the insurer's liability is contractual credit. Second, according to Article 30 of the Insurance Law in 1937, when a payment is settled by the insurer, the insurer has the right to refer to the tortfeasor on behalf of the insured. If, according to the well-known theory of nature of compensation in insurance, is assumed to be damage and reference to the tortfeasor entails the rule of "prohibition of double compensation", such a right will not be considered either for his/her subrogation (insurer) because the injured party’s claims are compensated for by the insurer’s compensation and it is not possible any longer to refer to the tortfeasor (originally or by subrogation). As a result, the nature of the insurer's payment should be considered to be based on credit and contract and there should be the possibility of referring to the tortfeasor on behalf of the insured. In other words, knowing the "nature" of the insurer's payment is the requirement for the justification of "principle of subrogation". Third, at the end of Article 30 of the Insurance Law in 1937, the legislator states that "the insurer will be the subrogation of the insured and if the insured takes any action contrary to the contract, s/he will be considered liable to the insurer". Any action contrary to the insured’s right, such as release from an obligation third party responsible and bringing an action for damage against the third party responsible by the insured (original) is valid when s/he has the right to quittance or initiation of lawsuit. If the nature of the insurer’s liability is damage and the insured has no right against the tortfeasor, how can s/he acquit the tortfeasor or claim any payment from him? Fourth, in some legal systems, such as the legal systems of the United States and Ireland, the injured party has the possibility to refer both to the operating losses (tortfeasor) and the insurer, and the system of "Collateral Benefits" is applied (English Law Commission's Consultation paper, 1997, No. 147, "Damages for Personal Injury: Collateral Benefits": P 75, At: www.lawcom.gov.uk). This suggests that the principle of subrogation is not due to the nature of damaging the insured's civil liability. What the insurer pays to the insured is the "credit" of the insured and the enforcement of the contract by the insurer; and the insured’s right to refer to the tortfeasor to receive "indemnity" is retained (which is referred to the tortfeasor by the insured in the "collateral benefits" system or by the insurer in the "recoupment" system on behalf of the insured.

Conclusions & SuggestionsThe nature of the insurer's liability in the insurance contract is demand and contractual. In our law, the "Recoupment" system is chosen on how to refer to the tortfeasor, and the insurer, after being compensated according to the insurance contract for civil liability and to compensate for the power of subrogation from the insured, refers to the tortfeasor. Knowing payment, the "nature" of the insurer's liability, the possibility of applying any of the Selection systems, Accumulation of Benefits, the Recoupment and the Relieving the Tortfeasor’s liability can be applied according to the requirements of time and place. It is suggested that the "Accumulation of Benefits" system be specifically reviewed by the legislator.

Keywords: subrogation, insured, insurer, Damage, recoupment -

Pages 103-142Introduction

One of the ambiguities existing in the insurance contract is the quiddity and nature of the insurer's liability in the insurance contract, which means whether insurer's payments is of the nature of a demand insured or real damage. The nature of the insurer's liability has a direct effect on the possibility of insured's referring to the tortfeasor and on the possibility of accumulating the damage imposer’s liability and insurer's liability (due to differences in origin). In this way, if the nature of the payments that the insurance company pays to the insured or the stakeholder is a credit (or savings or replacement of the contract), the injured party (the insured), after obtaining the insurance money from the insurer pursuant to contract, can refer to the tortfeasor because of the difference in the origin of liability (contractual and forcible) and the responsible person (insurance company and tortfeasor).

Theoretical frame work, Methodology, Results & DiscussionThere are several legal systems to compensate for the insured’s losses, the most important of which include: 1. Selection: This means that the damaged party can refer to one of the responsible agents (insurer or tortfeasor) at his/her own selection. 2. Accumulation of benefits: This system is operative according to the principle of capital and, thereby, the damaged insured can also refer to the contractual legal system in addition to entitlement to refer to the forcible liability. 3. Recoupment: The contractual liability (insurer) can refer to the forcible liability after the loss and damage was compensated for and demand the tortfeasor for compensation for the payment already incurred. 4. Relieving the Tortfeasor’s liability: This means that neither of the parties are entitled to refer to the tortfeasor (Cane, 2006: 377; Lewis, 1998: 17). The principle of subrogation, which has been approved by Iranian legislatures, is a subset of the recoupment system and entails the fact that the insurer should refer to the tortfeasor while the damage was compensated for and amount paid to the insured should be claimed for refund from the tortfeasor. In domestic law, the principle of subrogation is viewed to be based on the rule of "double compensation prohibition " and "prohibition of unjust ownership" and is interpreted on the basis of recognizing the insurer's payment to the insured as "damages". In other words, when the insurer compensates for the insured's loss by paying for the damages, the insured can no longer refer to the insurer because one of the pillars of the claim is the civil liability of damages survival. Thus, when the insured's damages were paid by the insurer, the insured does not have the right to refer to the tortfeasor but the insurer can refer to the tortfeasor on behalf of him/her (Babaee, 2005: 25; Taheri, 2008: 22). In this research, for the following reasons, it was proved that the nature of the insurer's payment has been a "credit" and the above argument is not correct. First, according to Article 1 of the Insurance Law in 1937, insurance is a commutative contract and the insurer's indemnity is paid for the insurance premiums paid by the insured. In addition, the insurer's obligation originates from the insurance contract; therefore, the nature of the insurer's liability is contractual credit. Second, according to Article 30 of the Insurance Law in 1937, when a payment is settled by the insurer, the insurer has the right to refer to the tortfeasor on behalf of the insured. If, according to the well-known theory of nature of compensation in insurance, is assumed to be damage and reference to the tortfeasor entails the rule of "prohibition of double compensation", such a right will not be considered either for his/her subrogation (insurer) because the injured party’s claims are compensated for by the insurer’s compensation and it is not possible any longer to refer to the tortfeasor (originally or by subrogation). As a result, the nature of the insurer's payment should be considered to be based on credit and contract and there should be the possibility of referring to the tortfeasor on behalf of the insured. In other words, knowing the "nature" of the insurer's payment is the requirement for the justification of "principle of subrogation". Third, at the end of Article 30 of the Insurance Law in 1937, the legislator states that "the insurer will be the subrogation of the insured and if the insured takes any action contrary to the contract, s/he will be considered liable to the insurer". Any action contrary to the insured’s right, such as release from an obligation third party responsible and bringing an action for damage against the third party responsible by the insured (original) is valid when s/he has the right to quittance or initiation of lawsuit. If the nature of the insurer’s liability is damage and the insured has no right against the tortfeasor, how can s/he acquit the tortfeasor or claim any payment from him? Fourth, in some legal systems, such as the legal systems of the United States and Ireland, the injured party has the possibility to refer both to the operating losses (tortfeasor) and the insurer, and the system of "Collateral Benefits" is applied (English Law Commission's Consultation paper, 1997, No. 147, "Damages for Personal Injury: Collateral Benefits": P 75, At: www.lawcom.gov.uk). This suggests that the principle of subrogation is not due to the nature of damaging the insured's civil liability. What the insurer pays to the insured is the "credit" of the insured and the enforcement of the contract by the insurer; and the insured’s right to refer to the tortfeasor to receive "indemnity" is retained (which is referred to the tortfeasor by the insured in the "collateral benefits" system or by the insurer in the "recoupment" system on behalf of the insured.

Conclusions & SuggestionsThe nature of the insurer's liability in the insurance contract is demand and contractual. In our law, the "Recoupment" system is chosen on how to refer to the tortfeasor, and the insurer, after being compensated according to the insurance contract for civil liability and to compensate for the power of subrogation from the insured, refers to the tortfeasor. Knowing payment, the "nature" of the insurer's liability, the possibility of applying any of the Selection systems, Accumulation of Benefits, the Recoupment and the Relieving the Tortfeasor’s liability can be applied according to the requirements of time and place. It is suggested that the "Accumulation of Benefits" system be specifically reviewed by the legislator.

Keywords: Allocation of economic risk, Liability insurance, Indemnity against liability, Indemnity against loss, Right to indemnification -

Pages 143-170

This article tries to respond to this question that how we can analyze foreign investment sanctions against Iran in the light of regulations concerning on capital flow in international law? Finally, it can be understood that capital or foreign currencies are entered to or withdrawn from the states intentionally or unintentionally. Intentional restraints against inflow and outflow of capital might be contrary to some of the international obligations. This analysis should have been done in four chapter which consist of capital restrict and flow in international economy, capital restrict and flow in international law, foreign investment in international law: from promotion to restriction, and analysis of foreign investment sanction in Iran. Capital Restrict and Flow In International Economy Free flow of capital as a result of global trade liberalization has been a subject of the economists’ attention. There are different economic schools which have different view to capital flow. Capital flow isn't supposed in Mercantilism because of importance of import of capital and consequently increasing of gold storages of State. In Physiocracy school there is this belief that capital turnover is a natural rule. After that in economic liberalism the voluntary trade strengthened. In this view flow of capital is in the top of its possibility. In contrast, Marxism and Socialism were opposite with the freedom of capital movement. In Islam economy also there are subjective and objective limitations in trade. Keynesians believe that State should control on the capital inflow and outflow. In the view of Milton Friedman (New Classics) the right way is self-regulation of the market e.g. in capital trade. There is also the theory of Impossible Trinity in which respecting to inflow and outflow of capital and stability of domestic exchange is impossible. The superior view in the nowadays world is assimilate to Keynesians meaning that international organizations can supervise on the free movement of exchange and capital in the world. Capital Restrict and Flow in International Law (Structural View) As PCIJ stated as a principle States have sovereignty in regulating of currency movement. International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization, European Union, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Group 20 (G20), free trade agreements, and bilateral foreign investment treaties emphasize on this principle. There are also exceptions to the free flow of capital, which shall be restrictively and conservatively applied. In other words, after World War 2 Bretton Woods regime restricted this freedom. IMF advise capital movement and restrict it to economic infrastructures in the country. WTO allowed cash and non-cash capital inflow in TRIMS and GATS and restricted it balance of payments. European Union enforced capital movement and restricted it just in breach of tax law of members and public policy or public security. In OECD capital movement just can be restricted in economic crisis. Capital Restrict and Flow in International Law (Contractual View) multilateral trade treaty also supports from the capital inflow and outflow but some of them –like U.S. agreements- support of that more than others. In BITs if core term of definition of investment is non-physician capitals, so capital flow is supported better by free transfer clauses by which investor can transfer its currencies to foreign easily. Capital flow can be happen in nine type which include: voluntary inflow movement, involuntary inflow movement, voluntary inflow restriction, involuntary inflow restriction, voluntary outflow movement, voluntary outflow restriction (general), voluntary outflow restriction (special), involuntary outflow movement, involuntary outflow restriction. Capital flow just in three type of them: voluntary inflow restriction, voluntary outflow movement and voluntary outflow restriction. Foreign Investment in International Law: From Promotion to Restriction Although foreign investment trend increased in 1990 decades and States competed in encouraging of investors, but sometimes this trend decreased cause of some host State or national State policies or involuntary reasons like security of host State. Some economists believe that respecting of inflow of capitals for investment without restrictions isn't favorable. So States tried to restrict inflow of capital for investment which mostly happened by colonialized country. Analysis of Foreign Investment Sanction in Iran In investment sanction of Iran inflow capital sanction is due to some non-economic policies. These sanctions are against allowed exceptions set out in international law because goal of that exceptions are safe of economy of State. These sanctions breaches IMF rules as capital flow restriction just permitted where economic infrastructures are undermined or economic crisis is ongoing. These sanctions by EU States are violation of article 63 of Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, 2007 in which just public interests of States can be justify capital flow restrictions. In according to relations of Iran and United Stated of America, Treaty of Amity, article 7 of Economic Relations and Consular Rights, 1955 prohibited any restriction on payments, remittances and other transfers of funds to or from the territories of each other except to the extent necessary to assure the availability of foreign exchange for payments for goods and essential to the health and welfare of its people. In any way these restriction shouldn't be taken in discrimination. Although U.S. withdraw of Amity Agreement in 2018 but this treaty would be applicable till one year after withdrawal declaration and U.S. is responsible for the enforceable period. Also some bilateral investment agreements of Iran and other States mentioned to the free transfer clause. For example, investment sanctions by franc and Japan is against of their investment treaties by Iran in which capital flow restrictions just is allowable in situation of safe of balance of payments and protecting of debtors, as the same the treaties by Austria (with exception of balance of payments) and by Germany, Italy and South Korea without any exception. By adoption of JCPOA, EU and US obliged to seize investment sanctions on oil and gas and Petrochemical. So any capital sanction like re-imposition of sanctions by president of US is against several recognized international rules.

Keywords: Sanctions, foreign investment, capital flow, capital movement, The Islamic Republic of Iran -

Pages 171-196Introduction

Bilateral Investment Treaties can be considered as one of the most important sources of international investment law, which emerged with the aim of establishing customary international law in the form of treaties. Today, due to the efforts of capital exporting countries as well as support of some international organizations, the host state obligations towards foreign investors are increasing in these treaties, on the one hand, and investment arbitration tribunals provide broad interpretations of the host state obligations in favor of investors, on the other hand. This has led to the increase of claims against the host states, which have inflicted losses on them even greater than the returns derived from foreign investments. Though in the past foreign investors were concerned about protecting their capital and security in the host country, now, host states are concerned about restrictions on the exercise of their sovereign rights to regulate in the public interests (Habibzadeh & Gholami, 2018: 114). Due to the recent wave of riots, terrorism, wars and other forms of armed conflicts around the world, one of the most controversial issues in international investment law, which has so far been overlooked in its specific legal dimensions, is claims over armed conflicts. Some foreign investors invest in the countries involved in conflicts due to the opportunities for profitability in war situations, and even expect more profits (Zamani & Bazzar, 2018: 231), but due to the turbulent conditions in these countries, possibility of destruction and seizure of their assets increases, which results in the breach of investment treaties. In recent years, upon increase of claims of investors against the host states over domestic and international armed conflicts, it seems that the scale of investment claims has become heavier in the interests of the investors and therefore attention must be paid to protect the interests of the host states in such situations.

Theoretical frame workThe most important standard of treatment invoked by foreign investors in claims arising from armed conflicts is the standard of full protection and security which is designed to protect the investors and the investments against violent acts (Ostransky, 2015: 137). Almost all investment treaties contain the clause of protection and security, although they have used various terms such as full protection and security or sustainable protection and security. Since most of these treaties do not explicitly specify the nature and scope of protection of this standard, arbitration tribunals have interpreted this standard at their own discretion and, in some cases, preferred the interests of the investors over the interests of the host States in their awards regardless of the specific circumstances of the armed conflicts.

MethodologyAdopting a descriptive-analytical method and referring to the arbitration practices and investment treaties, this article seeks to clarify the nature and scope of full protection and security in the situations of armed conflicts in order to protect the interests of the host state.

Results & DiscussionReferring to the rules of interpretation of treaties in the Vienna Convention, this study determines that the standard of full protection and security refers only to the treatment of aliens in customary international law, and since the customary rule of treatment of aliens is a relative rule that pays special attention to the specific circumstances and resources of the host country, reflection of this customary rule in the treaty as a standard of treatment does not change its nature as a relative standard (Paparinskis, 2013: 160). As a result, arbitral tribunals, when examining compliance or non-compliance of the host state with the standard of protection and full security during armed conflicts, must take into account the specific circumstances of each country (Zeitler, 2001: 201) so that the interests of the host state are also protected. Another important point regarding the responsibility of the host state is that the host state will not be liable to the investors for damages caused by non-state actors who are not attributed to the state, unless it is proven that the host state has failed to take preventive measures and protect the investor against the non-state actors. Some arbitral tribunals have refrained to admit the conventional scope of full protection and security standard, which refers only to physical protection of the investors, and extend this standard to the legislations of the host states. (Dolzer & Schreuer, 2012: 243). This approach clearly means preferring the interests of the investor over the interests of the host state. If the parties to the treaty intend to extend the scope of this standard beyond its conventional concept, they must explicitly stipulate it in the treaty. However, if the term "full protection and security" is used in the treaty without any explanation, the arbitral tribunal shall not, at its discretion, provide a broad interpretation of the scope of the host State's obligations and then, on the basis of such interpretation, determine that the host state is in breach of the obligations it has not undertaken in principle and the treaty is silent on them.

Conclusions & SuggestionsIt is vital that shortcomings in the language of investment treaties and the ambiguity of standards in treaties will lead to different interpretations by arbitral tribunals. If countries explicitly stipulate their intentions when negotiating these treaties and specify the nature and scope of each standard, and leave no ambiguity, inconsistency of decisions in arbitrations will be reduced and a balance will be struck between the interests of the investor and the host state. As a matter of fact, Arbitral tribunals should notice that during the time of armed conflicts the host states are not able to provide the same level of protection for investors as they provide in peacetime, such as the rights of their own citizens which are different in peacetime vis-a-vis wartime, or in ordinary places vis-a-vis demarcated border areas. If a host state is to be held responsible for violating the standard of full protection and security during armed conflicts, the consequences of this violation must be evaluated in light of the state of emergency arising from such armed conflicts.

Keywords: Investment Arbitration, Armed Conflicts, Foreign investment Treaties, Interests of the Host state -

Pages 197-216

Although it is usually aesthetic when it comes to fashion and its concept, it is a way of looking at and thinking about certain things, subjects, and objects in a particular time and place within the concept. Fashion itself is a strong reason to place this issue in the context of intellectual property rights. Fashion-related rights (cover-beauty) are considered as one of the most important areas and areas of intellectual property rights that, with their monetization features, have an undoubted role in the flourishing of the industry. And the economies of the countries are playing. In French law, the historical record of fashion protection dates back to 1806, and the discussion of special protection for creations and clothing goods - as one of the most fashionable examples, formally introduced in the country since 1902 Has been. In addition to the adoption of a specific statute in this field after the aforementioned time-frame, pursuant to paragraph 14 of L-112-2 and Fifth Book of Intellectual Property Law (Articles L-511-1 onwards), garment-related products, seasonal industry, Designs and models, as well as cover and beauty creations, are examples of patents on industrial property rights, including patent, trademark, competition law, and industrial design. And. In Iranian law, it is possible to compare legal safeguards in this matter by comparing the rules and regulations governing industrial property and by adopting a common chapter between the rules governing industrial property law. The aforementioned claim is further reinforced when the Iranian legislator, pursuant to Article 4 of the Fashion and Clothing Regulations Act of 2006, produces designs and patterns, textiles and clothing based on Iranian-Islamic symbols, subject to the protection of authors 'and authors' rights and industrial property rights. Simultaneously, put together. Fashion in the word means new taste and new style, but in the term, it is a sudden change in taste of a group of people that results in a tendency to behave in a particular way or to consume a particular commodity or to promote a particular style of life. The term is close to words such as modernity, modernity and modernization. In medieval Europe, these words were avoided and the new and new category was described by the word "New". The new object (phenomenon) was a new one that belonged to the heavenly realm and came from God's creativity and divine creativity. In contrast, the "modern" and "fashion" phenomena belonged to the terrestrial and atrium. Fashion came from the human will for creativity and had a concept close to "innovation" in Islamic culture. But with the de-socialization of European social affairs in the Age of Enlightenment, words such as modern and modern were also sanctified and increasingly popularized. In addition, according to what some French writers have written, fashion can be defined as an aesthetic criterion accepted by a certain segment of society. In some French-language public cultures, fashion is defined as: "Fashion is a certain style and style of life and thinking in a particular period or country or place." As seen in this definition, in France, the definition of fashion is so broadly expressed that it encompasses even the type and way of thinking of a person at a particular time. Another important point about the above definition is that mention of words such as the particular "period", "country" and "place" brings to mind the relative and temporality of this concept. In France, the concept of fashion has been favored by the French legislature, as well as the formation of intellectual property law in that country, and in addition to legal writing, it has considered fashion as a framework for intellectual property rights protection., Are explicitly protected in the field of patronage in the field of law, seasonal and cosmetic industries including apparel, leather, cosmetics, etc. With the development of the concept of industry, fashion-related creative rights as one of the most important manifestations of intellectual property rights, have their own doctrine and doctrine, and to a considerable extent protected. It has the capacity of legal protection. Fashion-related creations, irrespective of their widespread and varied concept and application, from the aspect of industrial property rights, to French law, as outlined in the legal literature on this subject, within the context of various instances, including design supervisory rights. Models, patents, industrial designs, trade secrets, trademarks, etc. are protected and the provisions of each of the above will apply. In Iranian law as well as in French law, as in French law, and in the interpretation of this discussion, however, there has been little talk of French industrial law, however, with its reliance on the teachings of French industrial property law and comparison. It can be found with the laws of Iran and the Islamic-Iranian criteria, as well as the application of the rules governing each case of industrial property in relation to this subject, the terms and conditions of joint protection of this branch of intellectual property rights.

Keywords: industrial property rights, fashion, Industrial design, Patent -

Pages 217-240Introduction

Supervision of financial institutions, especially banks, in terms of implementing anti-terrorist financing laws and regulations is one of the most important issues highlighted in international instruments, and countries should work to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the system. There are various methods for supervising financial institutions, the most famous of which are the adaptive method and the risk-taking method. The adaptive approach, or the "one rule for all" approach, means that observers must inspect all of their supervised entities equally and use the same tools and make specific and similar decisions to break a rule. but, in a risk-based or risk-based approach, the amount of oversight is determined by the extent to which a financial institution is threatened and vulnerable. Achieve the goal of managing and reducing terrorist financing risks. In other words, in this approach, achieving this goal replaces by ensuring compliance with the law in financial institutions. The implementation of this strategy requires the establishment of legal bases and the implementation of executive measures; Therefore, on the one hand, the purpose of this study is to assess the feasibility of implementing a risk-based monitoring strategy in the light of the legal principles accepted in Iran's legislative criminal policy and on the other hand, to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the executive criminal policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran. In the field of supervision of financial institutions, this has been tried to achieve it by descriptive method.

Methodology The research is descriptive-analytical. Conclusions and suggestionsIn the legislature, regulators have no obligation to use risk-based methods and their decisions are not well supported. Existing performance guarantees, in addition to not being sufficient, are merely aimed at violating the prescribed rules. The supervisors have not been given the necessary authority, especially to enforce disciplinary guarantees in the event of violations of anti-terrorist financing regulations. In the field of executive criminal policy, a review of the instructions and procedures shows that in the market entry stage, it is sufficient to inquire only about criminal records; While, firstly, not all criminals are convicted, and secondly, criminals typically use covert means to obtain a license and keep their identities secret. In the field of periodic inspections, the need to provide information alone is not enough and there is no responsibility for supervisors to create a risk profile and provide a clear correction plan. The guidelines issued so far also promote a more law-abiding approach and focus on enforcing anti-money laundering regulations; Although these provisions are largely similar to those of terrorism financing, specific provisions on terrorist financing, such as how to seize terrorist assets and identify suspicious terrorist financing operations and transactions, have not been considered. Accordingly, in order to improve the effectiveness of Iran's criminal policy in relation to the financing of terrorism, in the first place, the issue of legal principles, especially the obligation of supervisors to use risk management methods, and violation of their decisions should be accompanied by heavy enforcement guarantees. Then, in the executive field, first, by measuring the risks of financing terrorism, applicants for obtaining a license for financial and non-financial activities should adopt an efficient method to prevent criminals and their associates from entering the financial markets; second, a national risk assessment must be conducted to ensure that regulators' information resources are largely adequate. Third, the necessary steps, such as creating a risk profile and drawing up a correctional plan for supervised entities by supervisors in each of the financial areas, must be taken. Fourth, violations of the correctional program must be addressed by disciplinary action by supervisors and the guarantee of administrative and judicial enforcement by the judiciary and related nstitutions. Fifth, guidance documents should be prepared and published in the field of detecting suspicious transactions and operations, as well as anti-terrorist financing regulations.

Keywords: Risk Based Supervision (RBS), Supervision, Counter-Terrorism Financing (CTF), criminal policy -

Pages 241-261

Commercial secrets are of economic value and not available to the general public, and reasonable efforts have been made to safeguard its confidentiality. In some cases, after the termination of the employment relationship of the former worker or employee, he or she is the cause for disclosure of the commercial secrets. This study, by studying the concept and the nature of commercial secrets and disclosure of commercial secrets responsibility, investigates the civil liability of commercial secrets disclosure by the former worker. The paper uses a descriptive-analytical method and benefits from library sources. As the finding of this paper the author concludes that the commercial secrets are defined as a sort of wealth or property and the access of the former worker to commercial secrets is a kind legal religious trust which can’t be denied and if the former worker (or employee) discloses commercial secrets, the base for his or her civil liability for the disclosure of commercial secrets and quality of distributing liability can be determined by benefiting from the principles of liability such as: usurpation, destruction, unjustified ownership or enrichment, deception and the liability for damages.

Keywords: Civil liability, comericial secrets, former worker, employee, Disclosure